Mervyn LeRoy, producer of The Wizard of Oz, directed this remake of a pre-code WWI melodrama based on Robert E. Sherwood’s play about a ballerina named Myra who falls in love with a soldier in London and then finds out that he is listed as dead. She and best friend, Kitty, turn to prostitution as a means to get by after having been sacked from the ballet company for misconduct. One day, however, she finds out her long lost lover isn’t really lost, but she must decide whether or not she can live with her decisions while he was away at war.

Mervyn LeRoy, producer of The Wizard of Oz, directed this remake of a pre-code WWI melodrama based on Robert E. Sherwood’s play about a ballerina named Myra who falls in love with a soldier in London and then finds out that he is listed as dead. She and best friend, Kitty, turn to prostitution as a means to get by after having been sacked from the ballet company for misconduct. One day, however, she finds out her long lost lover isn’t really lost, but she must decide whether or not she can live with her decisions while he was away at war.

Cast:

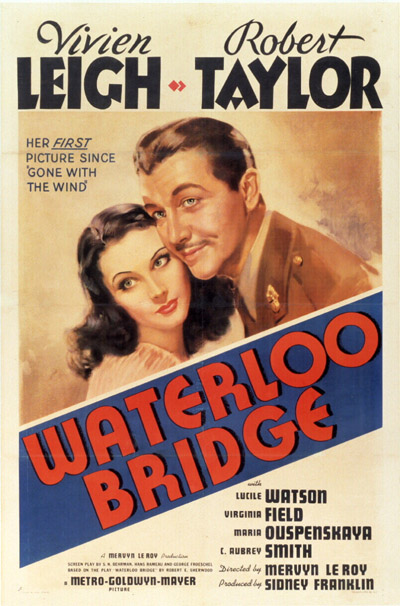

Vivien Leigh … Myra Lester

Robert Taylor … Roy Cronin

Virginia Field … Kitty

Maria Ouspenskaya … Madame Kirowa

Lucille Watson … Lady Margaret Cronin

Production Notes:

Directed by: Mervyn Leroy

Written by: S.N. Behrman

Produced by: Louis B. Mayer

Distributed by: MGM

Film location: MGM, Hollywood, California

Premiered: May 17, 1940 (USA) / November 17, 1940 (UK)

Behind-the-scenes:

• Adapted from the play by Robert E. Sherwood, this film is a remake of the 1931 pre-code version starring Mae Clark and Douglass Montgomery.

• The film, Vivien said at the time, was a classic example of miscasting. At the same time Waterloo was being filmed, Laurence Olivier was elsewhere on the lot playing Darcy in Pride and Prejudice. He had agreed to the part in the adaptation of Jane Austen’s popular novel on account that Vivien would be cast as Lizzie Benett. She was not. Greer Garson was given the role instead. Vivien, on the other hand, agreed to do Waterloo on account that Larry would be cast as Roy Cronin. He was not, which frustrated Vivien to no end. Hollywood producers seemed determined to keep them apart on screen.

Instead, Robert “The Perfect Profile” Taylor was cast opposite Vivien. In terms of the character, she was right: he was miscast. Roy is supposed to be a British soldier who lives in Scotland. Taylor made no attempt to put on any sort of accent, and his fake mustache to “make him look older” looks silly today. But Taylor–even though he was known more for his good looks than his acting skills–proved that he had enough charisma and enough chemistry with Vivien to make the film work. He said she helped his character immensely, and in the end, it was, for both Taylor and Leigh, the favorite film of their careers. One interesting fact about this film is that Vivien was given top billing above Robert Taylor due to her immense success the year before in Gone with the Wind. Also, contrary to popular belief, Waterloo Bridge was not filmed on location in London, but rather on the MGM backlot in California.

• Director Mervyn Leroy remembers: The first picture I directed after I went back on the sound stage was Waterloo Bridge. There were many who call it my best. My good friend, Jack Benny, says he considers it his favorite among all my films. Vivien Leigh, who co-starred in it with Robert Taylor, always said it was the best thing she ever did. Considering the fact that she had just done “Gone With The Wind” when she came to me, I consider that very high praise.

Naturally, after “Gone With The Wind”, Vivien was the hottest actress around. Everybody wanted her. She could have done anything she wanted to do. But she liked the property we had, which was based on the play by Robert Sherwood. It was a love story, pure and simple, and had been made before, as a silent film, by Universal. I had a great screenplay by Samuel Bierman. Sydney Franklin, whom I consider our finest and most sensitive producer, was our producer.

We had problems on the set with the fog; everything, or nearly everything, was supposedly set in the fog, and the sound stage was always full of the acrid smell of what the studio manufactured for the effect. But the fog worked to our advantage, too. We could suggest a locale, and the fog would be so thick we didn’t have to be too specific with our sets. There was one scene of Vivien walking on a bridge. All we did was build part of the sidewalk and string some lights across it, then fill the set with fog, and we had our bridge.

One of the key scenes was the one in a nightclub on New Year’s Eve, in which Vivien and Bob were supposed to meet and fall in love. He was leaving the next day for the front. It was a scene that Bierman, Franklin, and I had spent a lot of time on, and the dialogue between the two was, we had all thought, beautiful and tender. But on the set it just didn’t seem to work too well. I knew something was wrong, but I couldn’t put my finger on just what it was.

At four in the afternoon, after some hours of fruitless fiddling with the scene, I told everyone to go home. I sat there,in that make-believe nightclub, with just one small work light to give me illumination. Over and over, I read the scene, read the words that Sam,Sydney,and I had labored to get right. I was still there at two in the morning, when suddenly the answer came to me.

“No dialogue!” I said, aloud. “No dialogue at all!”

I realized at that moment what silent directors had always known, and what I should have known too. Often, in great emotional moments, there are no words. A look, a gesture, a touch can convey much more meaning than spoken sentences. Since sound came in, we had become dependent on it, perhaps over dependent on it. It was time to go back to basic human behavior, and often human beings say nothing. This scene was one of those times when silence was more expressive than dialogue.

That’s the way we played the scene. It started with a long shot of Vivien and Bob dancing on the floor, as the orchestra played “Auld Lang Syne.” Then I cut to the orchestra; each musician had a candle on his music stand; one by one, they snuffed them out. Cut to a close-up of them dancing, looking deep into each other’s eyes. Back to the orchestra and more candles being put out. Before all the candles were extinguished, the message was clear—they had fallen deeply,completely, in love. Not a word had been uttered.

Waterloo Bridge, old as it is today, still plays often on television and still brings tears to the eyes. Bob Taylor, in his later years, when he knew he was dying, grew sentimental. Most actors keep and cherish prints of their pictures, but Taylor had never had any. He told friends then that he would like a print of one picture he had made– Waterloo Bridge. The people at the Walt Disney Studio, where he was working at the time, got one for him, and he showed it often in his last few months.

Principal Photography

This film, in my opinion, is the one where Vivien looks most beautiful. This is due in great part to the photography of Hungarian, Laszlo Willinger. Willinger had immigrated to Hollywood after being discovered by Eugene Richee in 1937, and replaced Ted Allan as official production still photographer at MGM. In addition to his work on Waterloo Bridge (as well as his portraits of many other stars), Willinger took a series of portraits of Vivien and Larry that are now housed in the National Portrait Gallery in London. But for this particular film, his soft lighting contrasts marvelously with Adrian’s gorgeous costumes, and sets of Vivien’s delicate features wonderfully.

External Links:

Waterloo Bridge on TCM

Purchase the DVD

Reviews:

The New Statesman | by William Whitebait | November 1940 (*this review contains spoilers)

The first few shots of Waterloo Bridge almost finished me. War–this war–is declared. A colonel (Robert Taylor) with whitening moustache and astrakhan collar, gets off on his way to Waterloo Station and France, and stands on the makeshift bridge with that novelists call a lengthening face; a face in which (as the camera swings up from the river) are gathered wearily the Past, contempt of the present, and the sensations of a sea-sick llama. After what seems like a long, bad channel crossing of memories–the llama face flickers a little–the figure dissolves, and we are back in the Past, and in the thick of another war. A young captain (Robert Taylor) meets a ballet dancer (Vivien Leigh) during an air raid, and their falling-in-love is speeded up because he has to go off to the front a few days later. This part of Waterloo Bridge, despite a few absurdities due to an Anglo-American cast, is quick and charming and takes us alternately into the rigors of the ballet school and regimental mess. But then, as they are on the point of getting married, he has to go off, and the sentimentalities begin. She sees his name on a casualty list, hasn’t a job, goes on the streets, and he comes back to find her beating the precincts of Waterloo in black satin. Vivien Leigh, who up to now has done wonders with the part so long as freshness and vivacity were needed, isn’t so good in the dumps and with her hair down, and the neuroticism that leads to her street-walking and final suicide–on Waterloo Bridge need one add?–lacks conviction. If one began listing the tearful atrocities in which the director finally bogs himself and his cast, it would make the film sound a good deal worse than in fact it is. For there are compensations beside Vivien Leigh: good photography despite a camera fond of swinging; Maria Ouspenskaya as the martinet who keeps the young ladies of the ballet on their toes; Aubrey Smith having the time of his life as Colonel and Duke at the same time–he is far the most genuine period piece in this story. The enchanting air of Lac des Cygnes recurs as a sort of theme tune whenever the heroine is reflective. Each time it appears one is lifted out of the glaze of sentiment; and one is made, incidentally, to wonder why so talented a young dancer never gives another thought to the ballet once she is out of it.

TIME magazine | June 3, 1940

Waterloo Bridge (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer) is a drastic reworking of Robert Sherwood’s doleful drama about a love episode in Blighty during World War I—keyed up to catch the overtones of World War II, and toned down to meet the objections of censors. Waterloo Bridge is no longer a tale of a shy Canadian soldier who falls in love with a shy London trull. It is the story of a good-looking, upper-class British officer (Robert Taylor) who, during an air raid, conceives an undying passion for a good-looking ballerina (Vivien Leigh). After causing her to lose her job, he has to go off to the war before he can marry her. The young lady turns to prostitution.

Since the resulting tragedy hinges upon the doubtful moral notions of a lively British colonel (C. Aubrey Smith), who is not averse himself to a ballerina on the side, and the dancer’s somewhat unstable behaviorism, some people may find it less than tragic.

But Waterloo Bridge has its points. Expensively produced, it successfully continues Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer’s intensive he-manizing of Robert Taylor. Booted, trench-coated and sporting a dark, hairline mustache (the inspiration of Director Mervyn LeRoy), Cinemactor Taylor is a dashing officer. His continual kissing of Cinemactress Leigh may become a little tiresome to nonparticipants. But one kiss, after which the camera highlights and hangs suspended upon the languid Taylor lips, should go a long way toward rehabilitating Cinemactor Taylon with his fickle feminine fans and re-establishing him as a valuable studio property.