Back in April I had the pleasure of giving two talks on old Hollywood in San Francisco’s gorgeous and historic Presidio. The first, Vivien Leigh: Stardom and Screen Image, was at the Presidio Officers’ Club. The second, “How the glamour shot changed Hollywood,” was given at the Walt Disney Family Museum as a tie in for their current special exhibit, “Lights! Camera! Glamour! The photography of George Hurrell” (ends June 29, 2015).

As I mentioned in my last post, my interest in researching and writing about Vivien Leigh has not waned, but I am also eager to expand my knowledge on different subjects. So I was really excited when the Programs Manager at the WDFM invited me to give a talk about the history of glamour photography. Although I’ve loved looking at Hollywood glamour photographs since I first became a fan of classic films, I was less familiar with the details of their importance and the lives of the artists behind the cameras. I chose to highlight three photographers that represented three different eras of the studio system: James Abbe (whose archive I’ve been digitizing and cataloguing since January), George Hurrell, and Laszlo Willinger. The research was a lot of fun and the presentation itself went down pretty well, so I hope you enjoy it too!

*****

How the glamour shot changed Hollywood

Written and presented by Kendra Bean

Walt Disney Family Museum, April 11, 2015

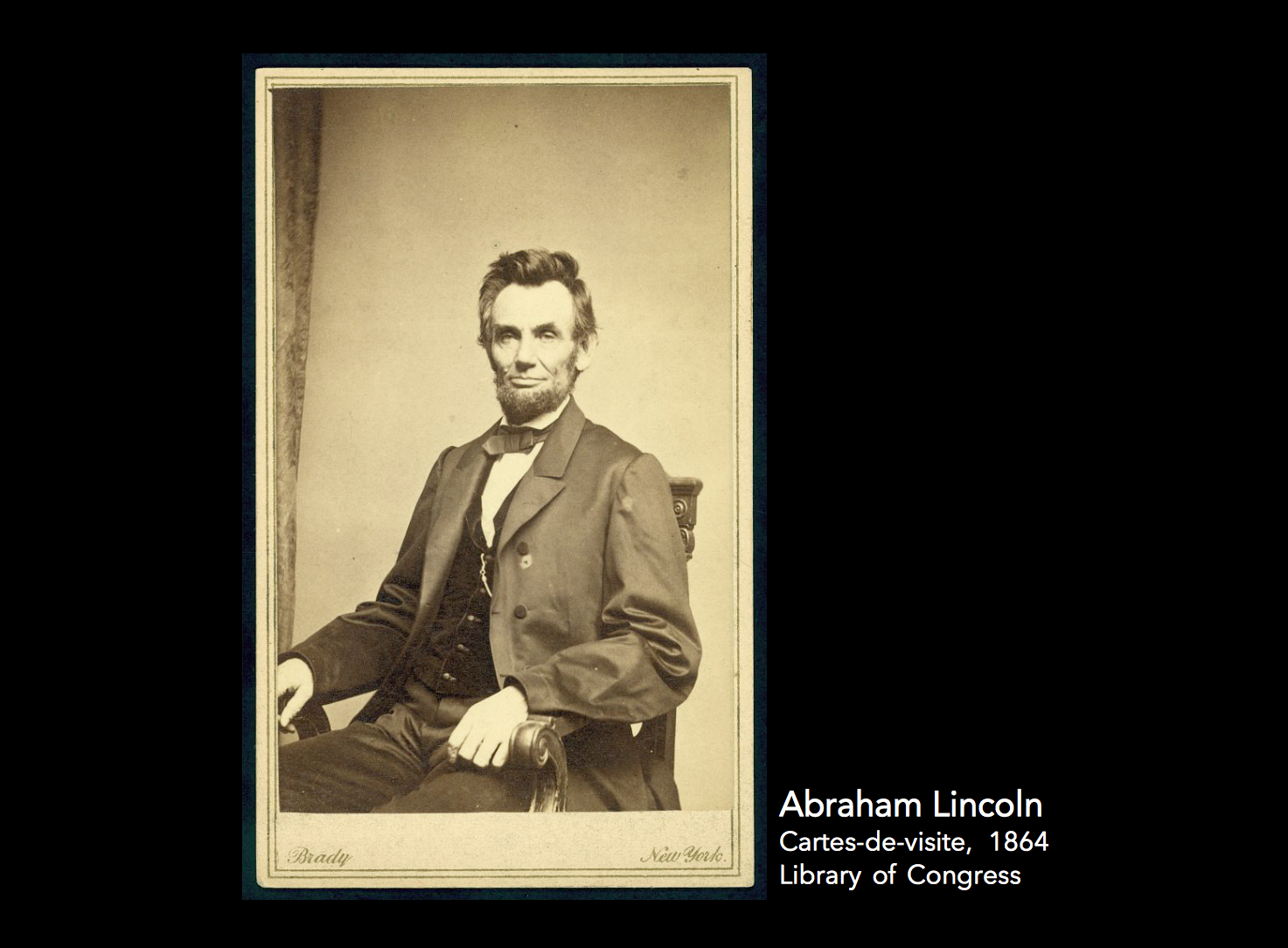

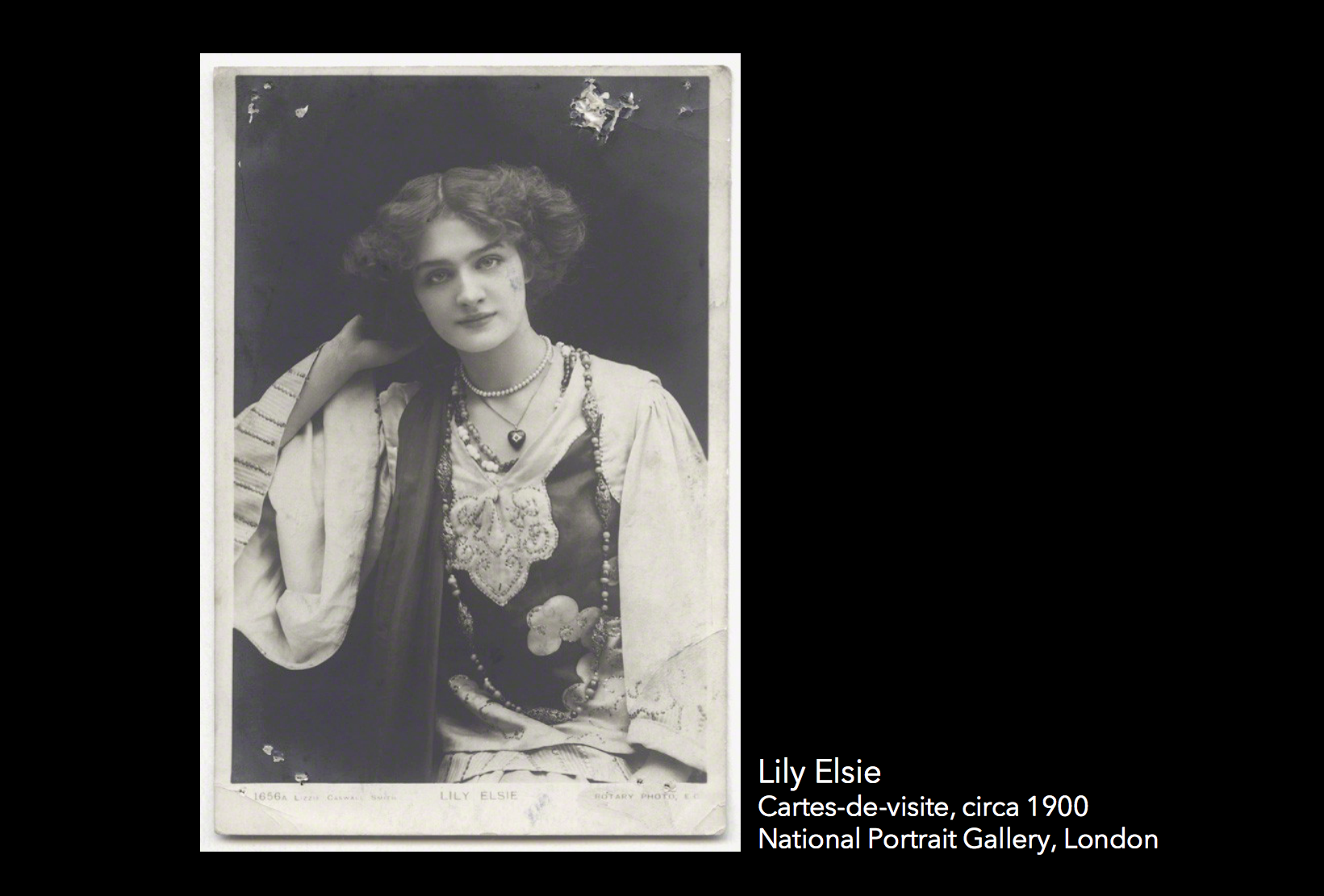

Interest in photographs of celebrities dates back almost to the invention of photography itself, and it definitely pre-dated the invention of the movies. During the American Civil War, 2 1/2 by 4″ cartes-de-visites were printed cheaply, collected en masse and traded or displayed in albums. Cartes were so popular amongst the general public that the phrase “cartomania” was coined to describe the phenomenon. Later, collectible postcards, cigarette cards and larger cabinet cards featuring famous personalities of politics, theatre and literature were also popular collectibles.

Although the concept of glamour had been part of Western culture since the 18th century, the term as applied to Hollywood came about in the 1930s to describe a style of photograph that captured the otherworldly beauty embodied by film stars. Glamour, like film stars themselves, was a carefully constructed illusion that was fed to the movie-going public, who in turn worshipped these God-like figures and fed their desires by purchasing tickets at the box office, thereby fueling the studios that produced the images to begin with.

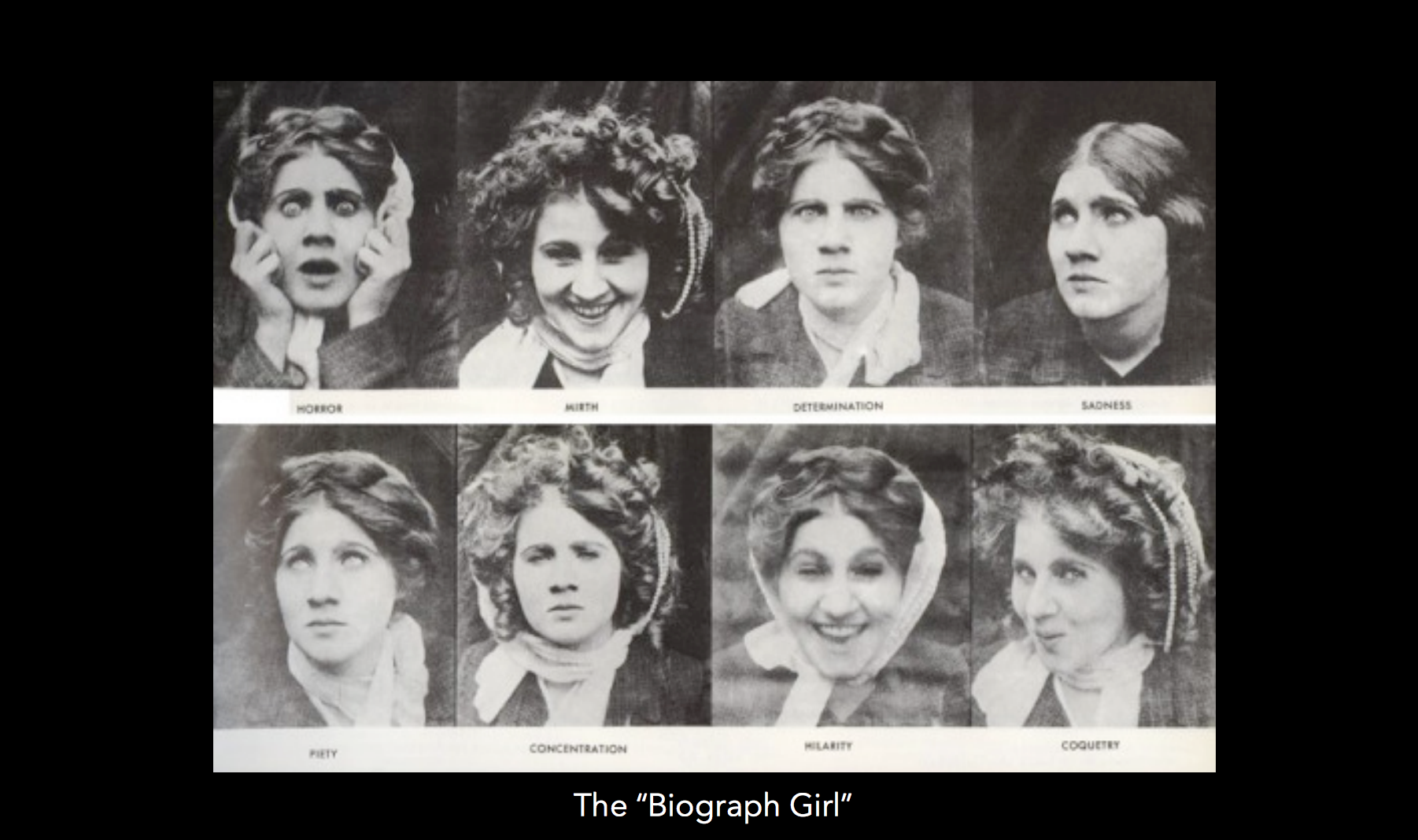

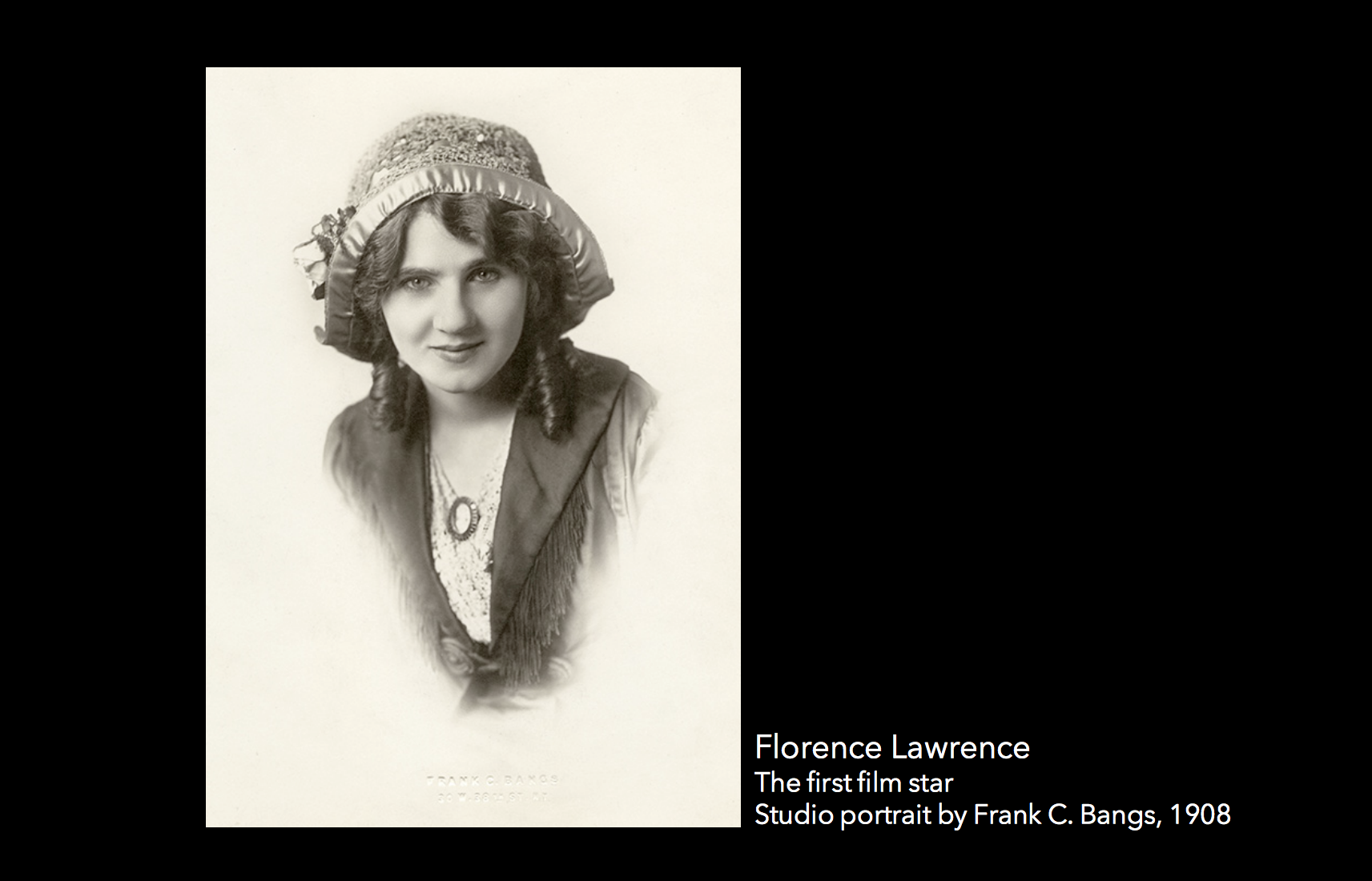

Glamour photography wouldn’t have been possible without the formation of something called the star system. In the very early years of cinema making, there were no such things as stars. Actors in films were anonymous, or known to the public by nicknames. Take the Biograph Girl, for example. Biograph was a film company run by D. W. Griffith, the director of Birth of a Nation and one of the most famous film producers of the silent era. He cast this young woman in several films, and audiences wrote in to the studio enquiring about her real identity. Griffith refused to release such information because he, like other producers, was afraid the ensuing fame would lead the actors under contract to demand higher salaries. She remained “The Biograph Girl” until 1909 when she joined Independent Moving Pictures Company headed by Carl Laemmle, the future president of Universal. Seeing the benefit of revealing the actress’ real name, Laemmle concocted a genius publicity stunt. He started a rumor that the actress had been killed in a car accident in New York. Once the rumor picked up steam, he placed her picture in several newspapers claiming his studio had uncovered the truth: that the actress, real name Florence Lawrence, was indeed alive and well, and making a new film for Independent Moving Pictures. A personal appearance in St Louis assured her fans that she was all right and thus Florence Lawrence, with the assistance of Carl Laemmle, became the first film star.

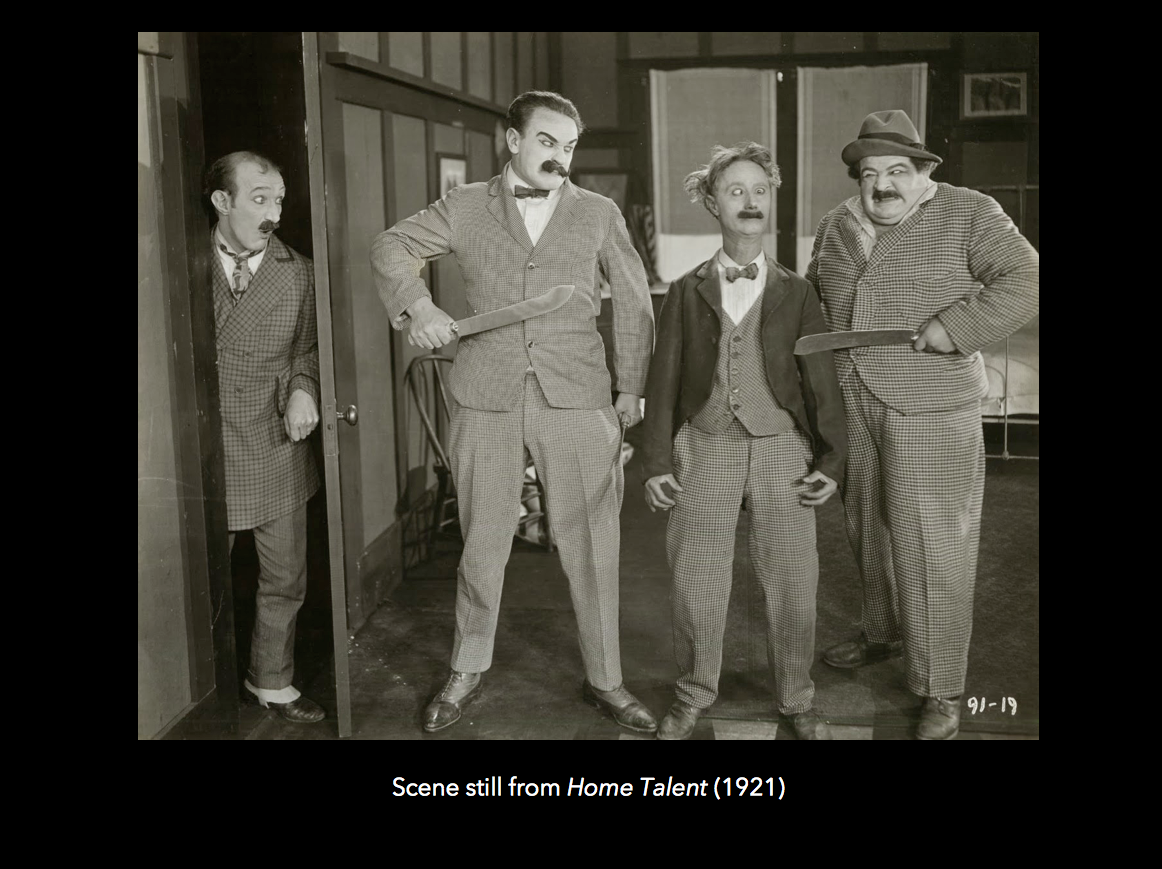

Once the studios became wise about creating stars to sell their films, thousands of people were employed to prepare, package and promote them. Photographers were part of the publicity department. Their photographs were sold to newspapers and fan magazines by the thousands, used to promote tie-in products, and appeared on film promotional posters and lobby cards. There were two different kinds of photographs taken while films were being made. One was the scene still. These were not stills captured from an actual film but rather posed images of actors in costume recreating scenes from a film. The second was the publicity portrait, usually taken in the photographer’s studio with the star or stars in costume or plain clothes before cameras started rolling. This meant that the stars and photographers had to come prepared with knowledge of the script and characterizations in order to transmit that to the camera. Portraits were also taken between film assignments and supplied to news outlets to make sure the star remained in the public eye even when he or she wasn’t currently on the big screen.

The whole enterprise was carefully planned out in advance. Historian John Kobal explained the preparation that went into running a publicity campaign:

“A campaign meeting was called before every picture was begun. There might be eight films in production at once, and one publicist and two assistants were assigned to each. Someone responsible for putting the campaign together would be there from the photography department to ask questions. What’s the film about? Are the costumes going to be of particular interest? The sets? How’s the star going to look? The meetings covered magazine and newspaper stories – what photos, spreads, and off-stage portraits would be used to sell the film?

“Once the copy for a campaign was approved, it was sent to the planting department. Five people did nothing but place [or plant] stories in newspapers and magazines; these had some factual basis but were generally puff pieces…The ‘planters’ worked closely with the editors and would get them to use photographs of up-and-coming stars in return for exclusive photographs of established stars. Ideal Publications put out five or six fan magazines for which the studio portrait gallery was always taking photos.”

The studio bosses also understood how important fans were to keeping their industry going. Magazines often included forms that readers could fill out to receive 8 x 10 photographs of their favorite actors, and portraits (usually signed by secretaries) were mailed out by the thousands. In fact, a star’s standing at a particular studio largely hinged on how much fan mail they received. So it was a real give and take system and the photographers played a central role.

During the silent film era, before the big studios conglomerated, producers often employed one photographer to cover all of the bases. Madison Lacy, who later worked for Warner Bros. but started in Hollywood around 1916, described what it was like to work in Hollywood during the very early years:

“When I first started out, you handled slates, loaded cameras, timed the shots, fero-tagged the fero-tag tin, dried the prints, loaded, made copies. We had to develop our own prints, which we did in a piro soup that made our hands as black as coal, because on the set you don’t always have the lights you like, so in your printing you learned to burn in something that’s very hot or hold back something when there isn’t enough light. You also had to do your own retouching. Anything at all that had to be done, you did.”

Another photographer who filled this multi-disciplinary role was James Abbe.

JAMES ABBE

I wanted to talk a bit about this particular photographer because I’m currently helping his estate digitize and catalogue his archive. The James Abbe Archive, based in San Francisco and Redding, California, consists of approximately 5,000 objects ranging from original prints to negatives (including glass), letters, newspaper cuttings, radio shows and the unpublished manuscript for his autobiography. The scope of this archive has great cultural significance. Abbe was both a portrait photographer and photojournalist. His work has appeared in publications as diverse as Vanity Fair, Shadowland, the New York Times, Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung and Vu.

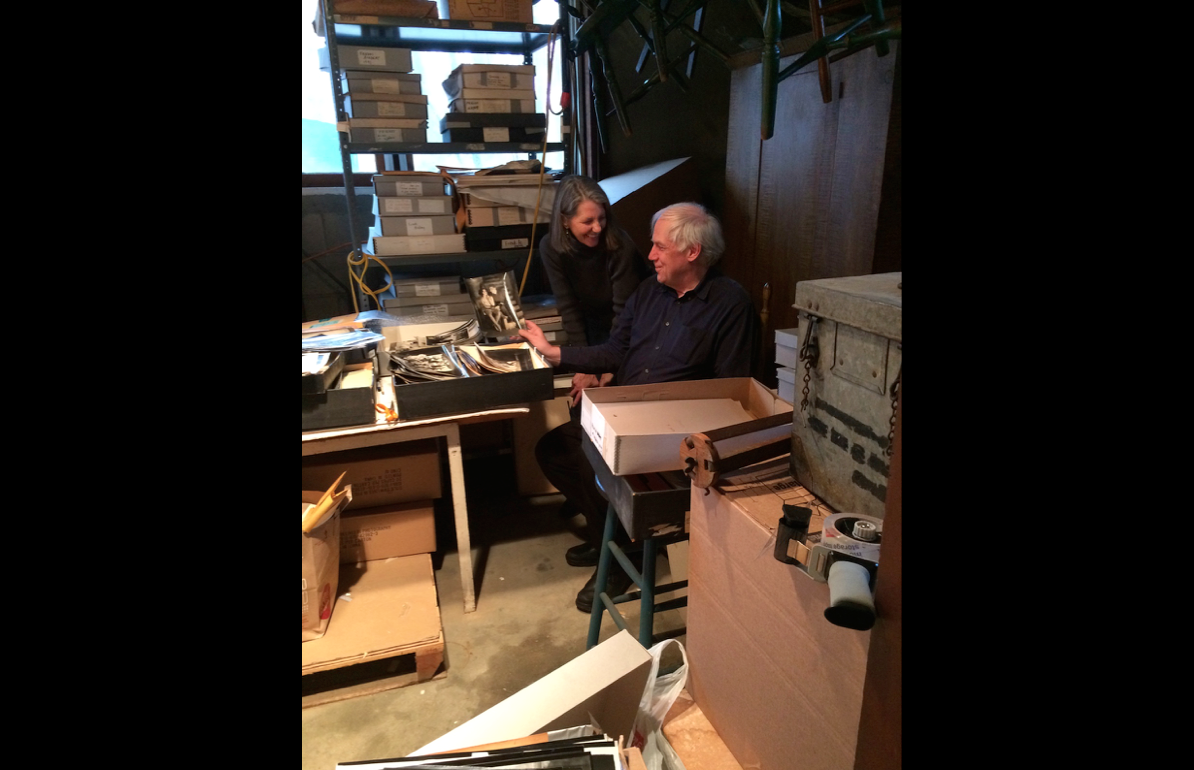

Jenny Abbe and photographs curator Terence Pepper sort through Abbe’s photos in New York.

James Abbe was born in Alfred, Maine, in 1883. His father, James Sr., worked in the book trade and moved the family south to Newport News, Virginia where he opened his own store. It was here at age 12 that the young James Abbe became interested in photography. After seeing his sister’s boyfriend with a portable Kodak camera, Abbe convinced his father to start selling cameras and other photographic equipment to his customers. Acquiring an Eastman Kodak pocket camera, Abbe could often be found snapping pictures of interest around town. His atmospheric shots of the shipyards, troops going off to fight in the Spanish-American War, and other topics of local intrigue earned him the nickname “the boy photographer of Newport News.”

At 23, Abbe went professional when he was contracted by the Washington Post to visually document the Great White Fleet of American battleships traveling to England and France in effort to impress (and possibly to intimidate) Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany. An image of the battleship USS North Dakota trudging through a storm tossed sea in the Bay of Biscay was snatched up by several European publications.

The Washington Post assignment was a success, but as anyone who has tried to make a career out of freelancing knows, you often have to supplement it with other work until you can make it into a career of its own. Returning from Europe, Abbe was offered a job at the J.P. Bell publishing company in Lynchburg, Virginia and during this time began experimenting with portraiture using subjects from the nearby Randolph-Macon Women’s College, which were published in the College annuals. It wasn’t long before Abbe had built up enough confidence in his portraiture to show a portfolio of his work to editors of major magazines like Vanity Fair. In 1917, encouraged by the response, he moved with his wife and three children to New York where he set up an independent photographic studio on West 67th Street.

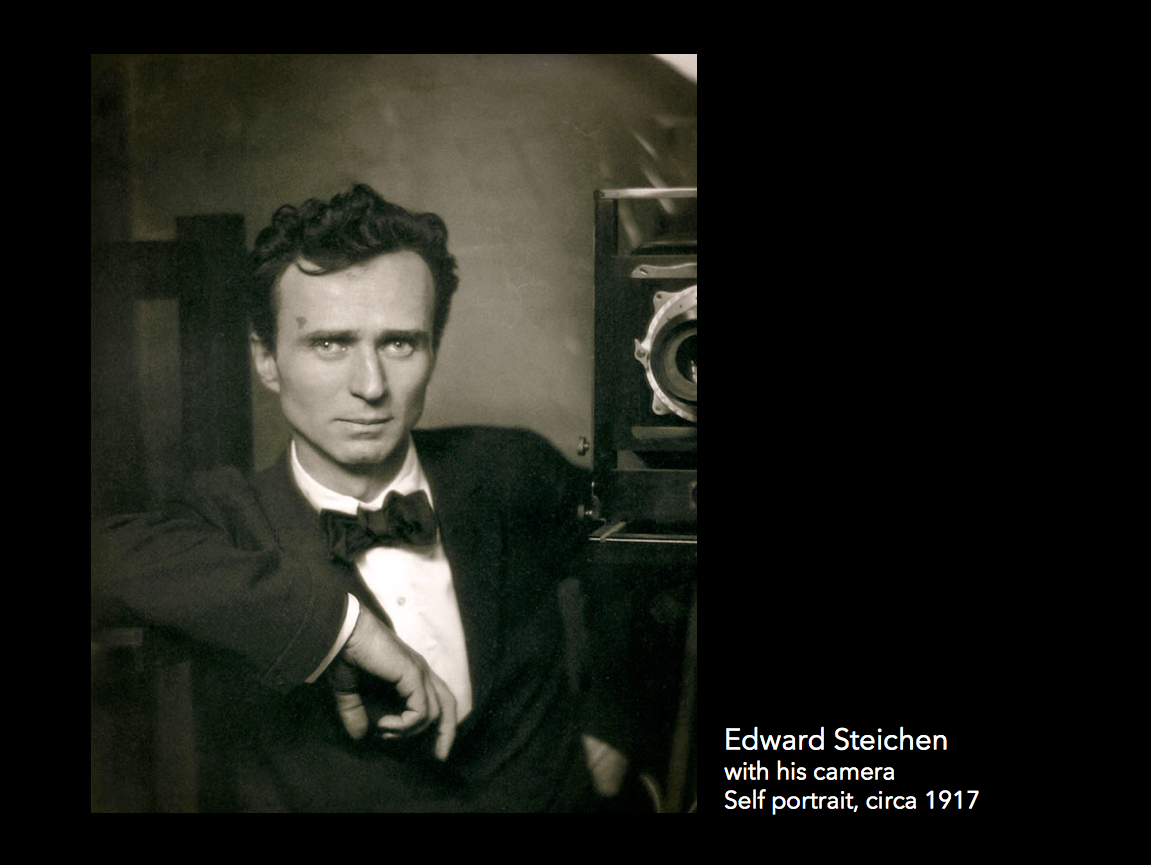

Abbe was influenced by and took inspiration from the best of the best. During his lifetime, Edward Steichen was considered one of the greatest photographers of the 20th century. He excelled in many areas, including fashion, advertising, nature, documentary and war photography. His portrait subjects ranged from Gloria Swanson to Henri Matisse to James Abbe’s daughter Patience. He was also one of the first photographers to experiment with color, and worked for a time as the Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The interwar period saw photographic technology and experimentation grow by leaps and bounds. Steichen, along with many European photographers, employed the ideas of New Objectivity, an artistic movement that flourished in Germany during the 1920s. Unlike the abstract Expressionist movement, New Objectivity as applied to photography moved away from the dreamy and romantic, and instead produced sharply focused, objective images. Like Steichen, James Abbe would apply similar ideas to his portraits.

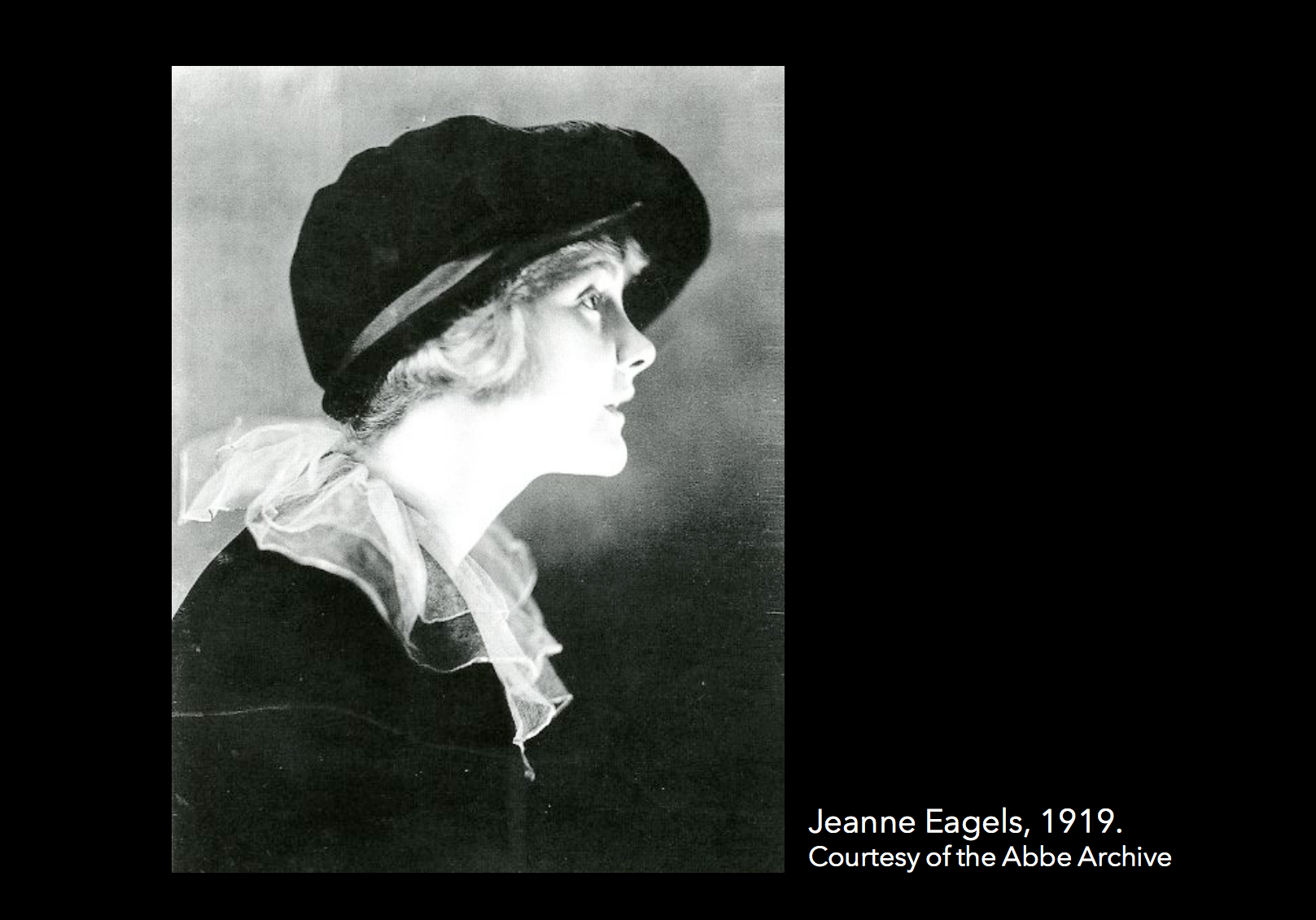

In the 1910s, the fledgling American film industry was split between Los Angeles and the East Coast. As a freelancer in New York, not bound by exclusive contracts, Abbe was free to photograph at his leisure and commercialize his work by selling prints to several different publications, often being paid twice for having the same photo published in different magazines. Abbe photographed the dancers of the Ziegfeld and Greenwich Village Follies, and film stars like Rudolph Valentino and Natacha Rambova, Fred and Adele Astaire and Mae West using both studio and location settings. One of his 1919 portraits of Broadway star Jeanne Eagels was the first photograph to land the cover of the Saturday Evening Post.

Most of the famous Hollywood photographers had working relationships with one or two stars that solidified their reputations. George Hurrell had Joan Crawford. Clarence Sinclair Bull of MGM had Greta Garbo. Bob Coburn at the Goldwyn Studios had British actress Merle Oberon. And James Abbe had Lillian Gish.

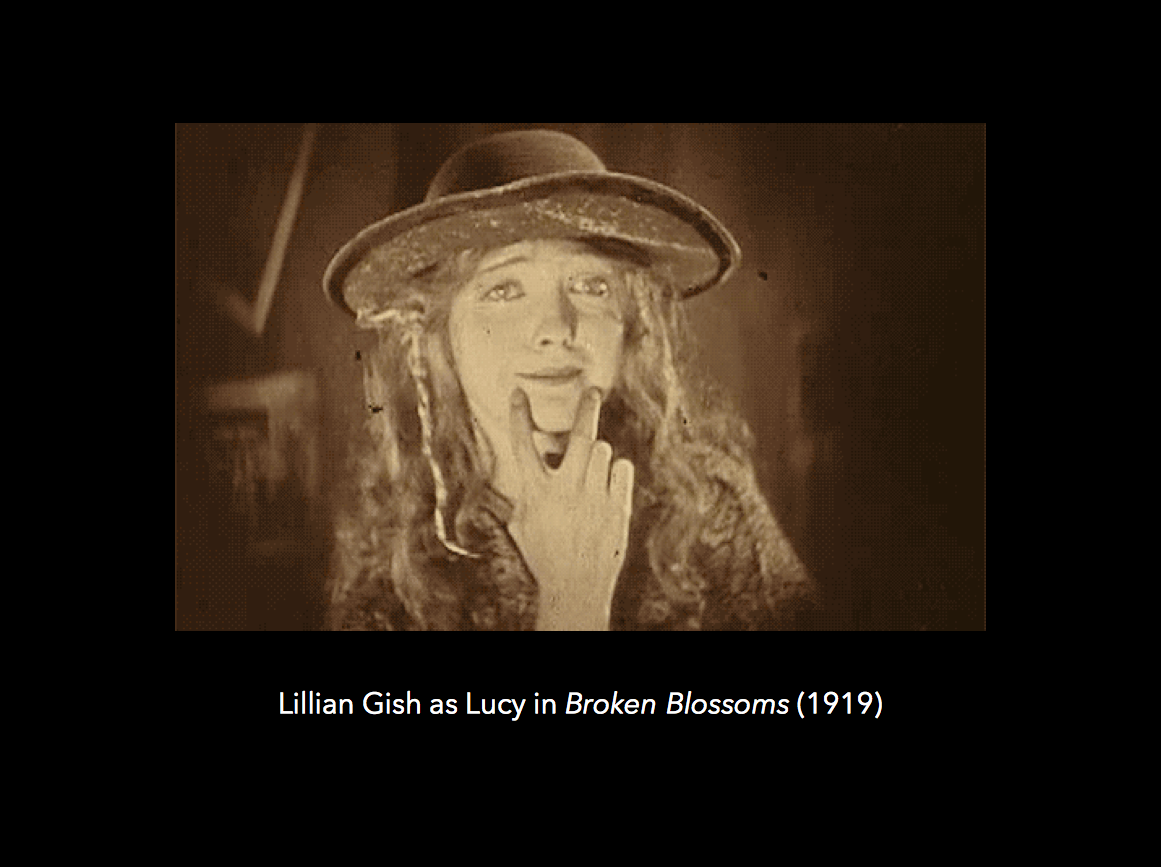

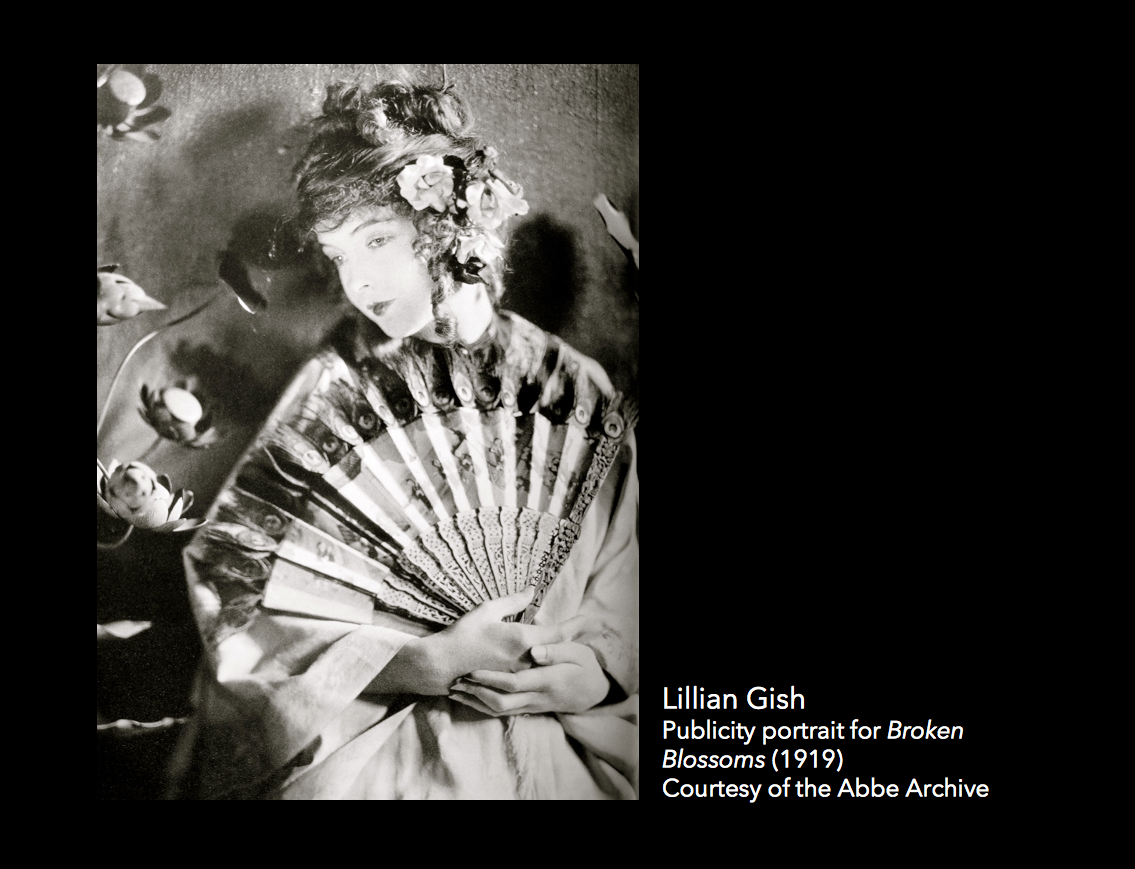

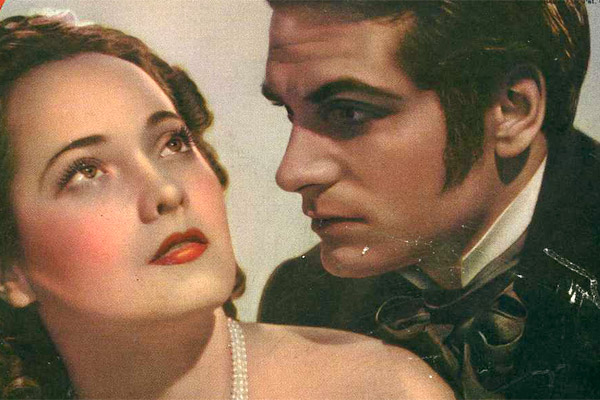

They first worked together when Abbe was commissioned to photograph Gish in costume for the 1919 D.W. Griffith film Broken Blossoms. Gish always played the pure and angelic waif in her films. Frail and hauntingly beautiful, her characters often endured intense suffering. In Broken Blossoms, she plays Lucy Burrows, a young girl living in London’s gritty East End. After suffering at the abusive hands of her alcoholic father, Lucy meets a kind-hearted Chinese man (played by white actor Richard Barthelmess) who takes her in and nurses her back to health. They fall in love, but it ends in tragedy. Throughout the film, Gish’s expressions of solemn sadness and fear are cleverly captured in an array of close-ups. In fact Gish became so famous for close-up shots that when she starred in the 1987 film The Whales of August, director Lindsay Anderson told her after one particular take that she had given him a perfect close-up. Her co-star Bette Davis supposedly quipped: “She should. The bitch invented them.”

In her heyday, Lillian Gish was one of the most recognizable faces in silent films. She also had a lot of control over what films she appeared in and who she worked with. Abbe’s photos for Broken Blossoms perfectly capture Gish’s virginal innocence. The serene, Madonna-like pose and speaks of the image she projected on screen, while the mid-length shot, theatrical flowers and fan recall the romanticism of the Edwardian era from which Gish emerged.

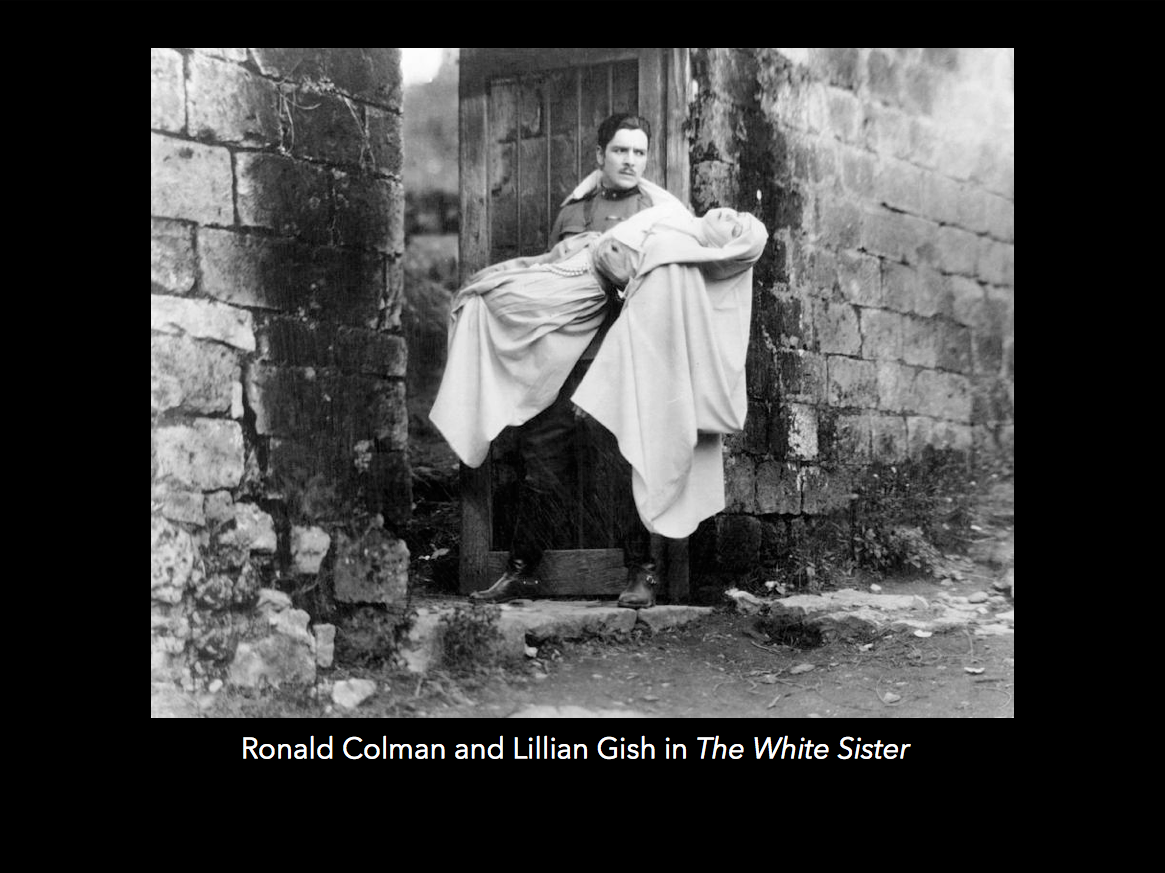

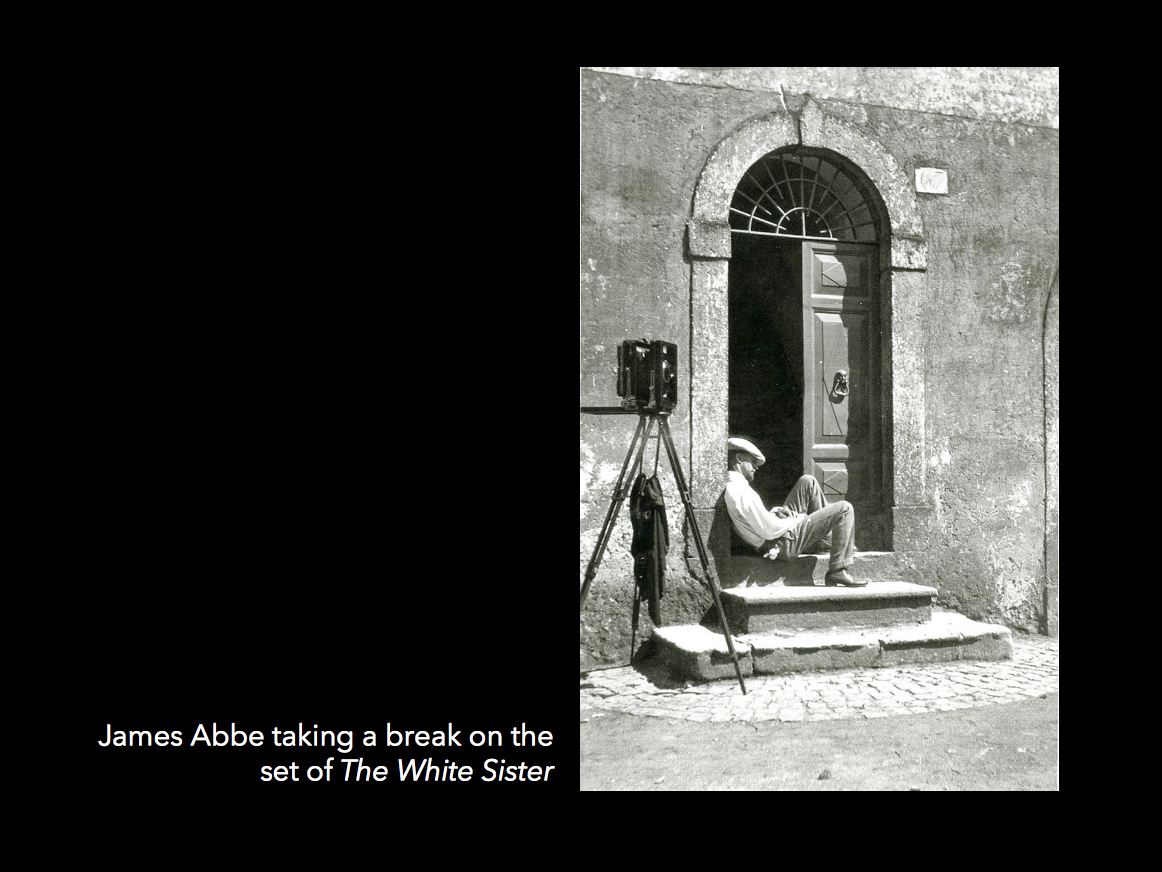

Gish liked Abbe’s photos so much that she requested him for several other films, including Orphans of the Storm, Way Down East, and The White Sister, during which Abbe served as both stills and portrait photographer. The White Sister is particularly notable because it was filmed in Italy and the desert of Lybia rather than at a studio in the United States. This meant that Abbe had to lug his big camera to locations like Mount Vesuvius. He even had a bit part in the film, playing a dying Italian soldier. But perhaps his biggest contribution to the film and to cinema history (aside from his wonderful photographs), was his discovery of British actor Ronald Colman, who was hired to play Lillian Gish’s love interest and went on to become a major star bridging the perilous gap between silent and talking pictures.

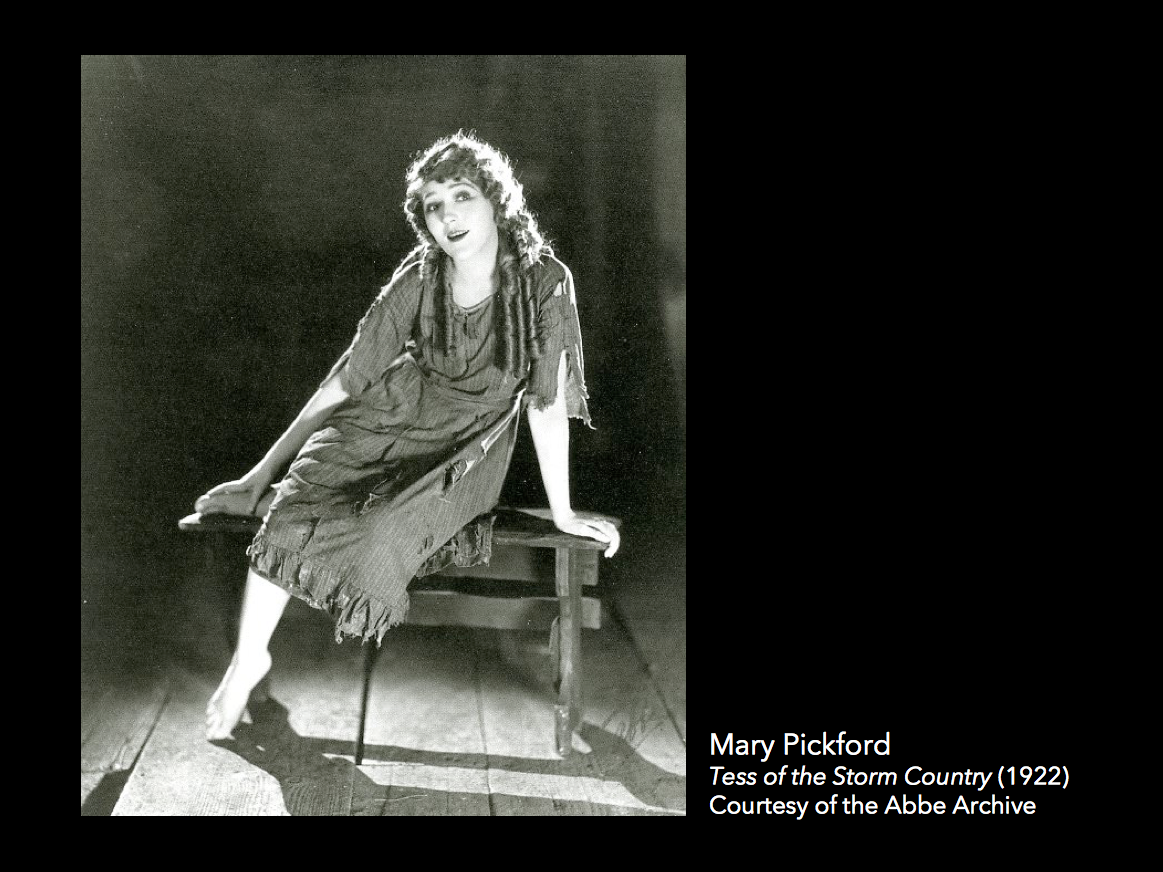

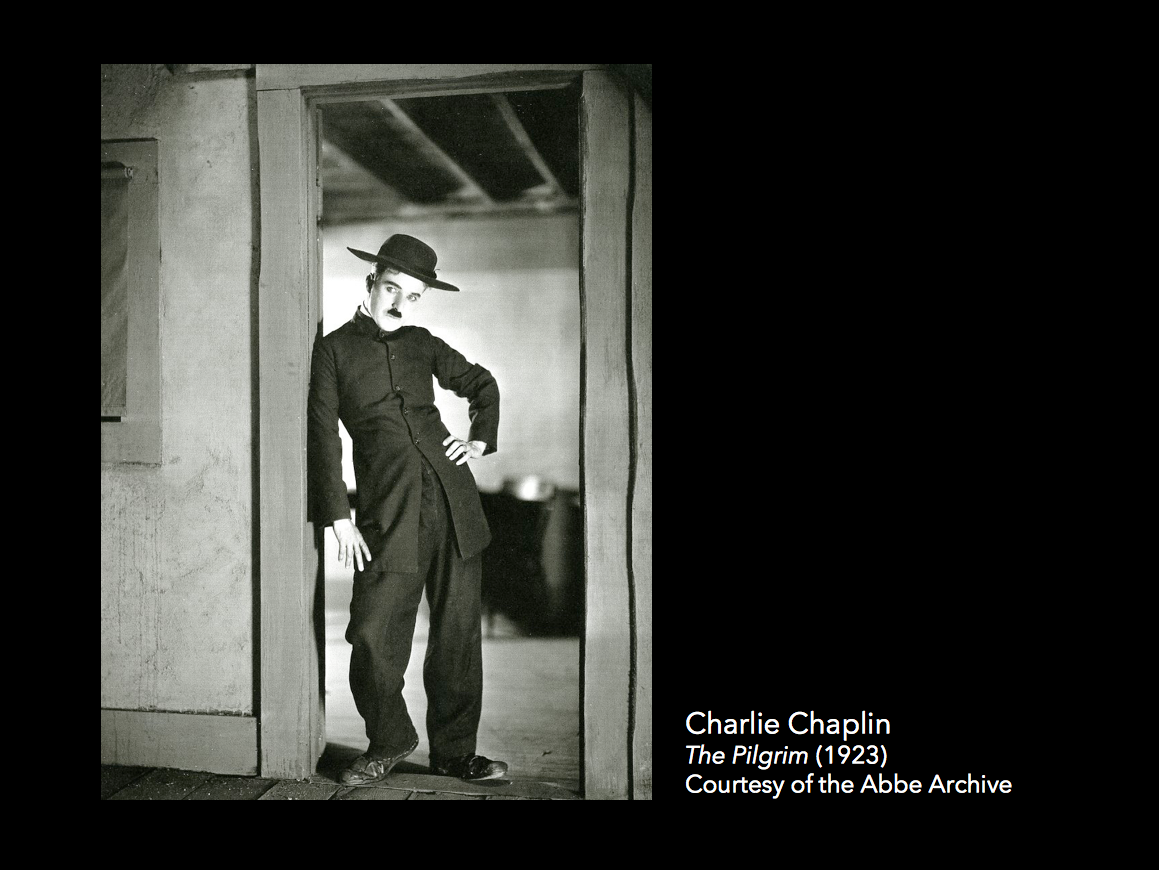

Abbe’s experience in the film industry extended to Los Angeles, as well. At the encouragement of Gish, Griffith and other New York acquaintances, he travelled west to try his luck in Hollywood and in 1920 and 1922 he produced what amounted to a broad survey of life and work in the fledgling movie capital. “Show business, in which I was up to my eyes, does not allow for delayed or cancelled appointments,” he said. “ Any who have ever been in the acting of producing business, on stage or in the movies, soon learn that time is of the essence. Punctuality is a necessity rather than a virtue. Only a few stars, regarded as irreplaceable or temporarily indispensible, can be tardy. Over the years I found show business people dependable, considerate, and easy to get along with. Mary Pickford once posed for three hours on her Hollywood set after a day’s work making a movie when it was her birthday.” “Charlie Chaplin was, and probably still is, a tight wad,” Abbe noted. “ None of the others on the Sennett lot was a spendthrift, but on the other hand, none was willing to go to the extremes Charlie Chaplin did, paying the lowest possible salaries while amassing fortunes.”

As a freelancer, Abbe’s work appeared in various fan publications, most notably Photoplay and the very popular arts magazine Shadowland. He also formed a close friendship with producer Mack Sennett who turned out comedies at his Keystone Studios in Los Angeles. Abbe was hired to work 10-hour days at $500 a week photographing Sennett’s famous Bathing Beauties, and even got hired to direct and produce his own feature film. Stills from the picture survive, but according to a major study by the Library of Congress, 70% of the silent films made in the United States are now considered lost, and Abbe’s film Home Talent is unfortunately one of them.

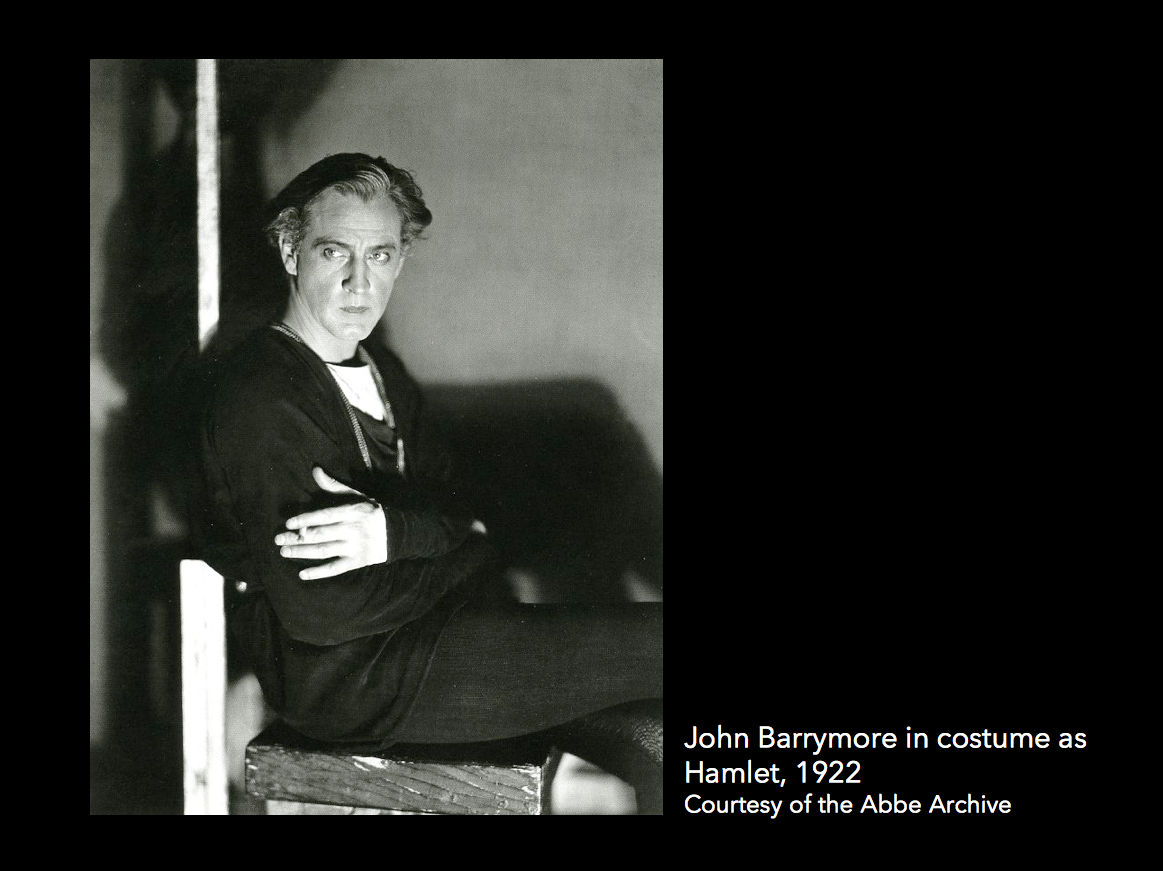

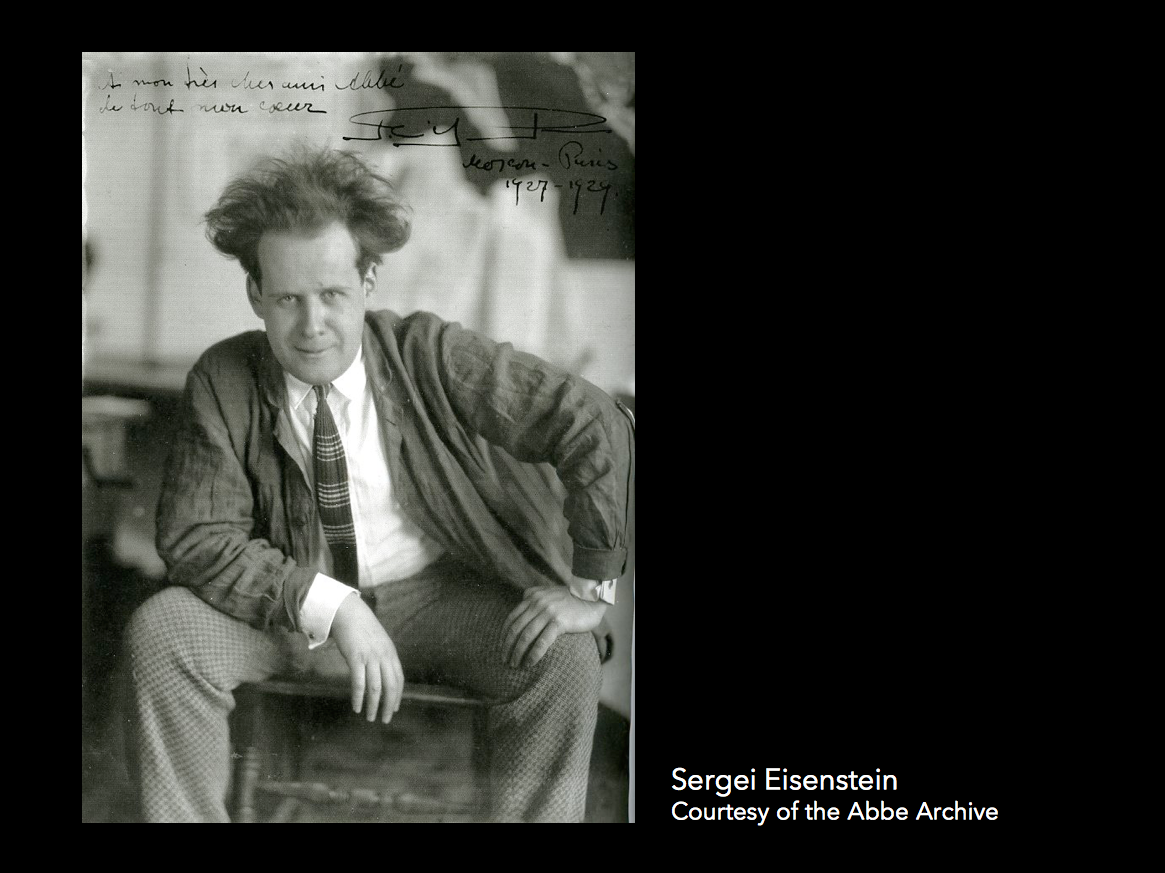

Abbe left the United States in 1923 and settled in Europe where he turned his attention back to photojournalism and news reportage. Traveling through England, France, Germany and Russia, he photographed Louise Brooks, the quintessential flapper then in Europe enjoying a lucrative collaboration with German film director G.W. Pabst; John Barrymore backstage during his landmark run as Hamlet in London. He found Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein in Paris, and even photographed Hitler and Stalin in Munich and Moscow, respectively. Throughout the ’20s and ’30s, Abbe managed to keep his finger firmly on the pulse of culture and politics during this rapidly changing time. And although his time in the film industry was but a small part in a much broader career, his photos of the top stars of the silent screen are what he is most remembered for today.

Stay tuned for part 2 of How the glamour shot changed Hollywood…

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠