All of the posts this week are my contributions to the For the Love of Film: the Film Preservation Blogathon that is being put on by the Self-Styled Siren and Ferdy on Films in effort to raise money for the National Film Preservation Foundation. As film lovers, we should all be aware of how delicate film is and how much of it has been lost due to improper preservation. Luckily for all of us, there are individuals who have made careers out of restoring and archiving movies so that we are able to enjoy them, and so will future generations. To donate to the National Film Preservation Foundation, please click HERE.

———

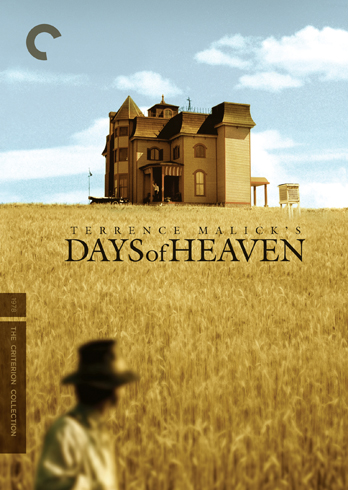

Terrence Malick’s 1978 film Days of Heaven is a visual masterpiece. In fact, I’ll go as far as to say it’s one of the most visually stunning films I’ve ever seen. The story is quite simple on the surface: a young couple on the run in 1916, along with the boy’s younger sister, hitch a ride on a train to the Texas panhandle and work as seasonal harvesters on a young man’s farm. A love triangle forms between the boy Bill, girl Abbey, and the farmer (played by Sam Shepard) that ultimately leads to tragedy. All of the performances in this film are top notch (even Richard Gere, who usually isn’t one of my favorites), but I think Linda Manz totally steals the show. The story is, after all, told in a through her naive eyes, which gives the film a sort of fractured feeling. Manz has such a beautiful, haunted quality on screen.

The photography is really central in Days of Heaven. Malick and cinematographer Nestor Almendros (who won an Oscar for his camera work) wanted to pay homage to silent cinema and have images take precedence in the story. They also wanted to use as much natural lighting as possible to make it look more authentic. Alberta, Canada was chosen as the location for filming because of its breathtaking scenery (as seen in other films such as Legends of the Fall), and Malick and Almendros paid special attention to the use of color, which, in Criterion’s restored version is absolutely breathtaking. Everything in this film feels authentic to its period setting, including the farmer’s mansion, which evokes scenes from George Stevens’ Giant, and was built with full interior and exteriors by art director Jack Fisk. The opening credits even use authentic period photography, including famous photos by Lewis Hine. And let’s not forget Ennio Morricone’s haunting score, one of the most beautiful of any film. Malick’s vision was to be “a drop of water on a pond, that moment of perfection.”

To put it plainly, Days of Heaven is a work of art. From the sweeping shots of thunder clouds and vivid sunsets, to a plague of locusts, to an isolated mansion in the snow, every image in this film is like a painting. I think Malick certainly achieved a moment of perfection with Days of Heaven, or about as close as one can get to perfection on film. It is a period piece, an avant garde film, an epic. It is simply mesmerizing in so many ways.

In the Criterion essay about the film, historian Adrian Martin describes his thoughts after seeing Days of Heaven in the theatre:

I vividly remember the experience of sitting in a large, state-of-the-art theater in 1978, encountering this work, which seemed like the shotgun marriage of a Hollywood epic (in 70 mm!) with an avant-garde poem. Wordless (but never soundless) scenes flared up and were snatched away before the mind could fully grasp their plot import; what we could see did not always seem matched to what we could hear. Yes, there was another “couple on the run”—Richard Gere and Brooke Adams as the lovers Bill and Abby, he fleeing a murder he inadvertently committed working in a Chicago steel mill, she pretending to be his sister during the wheat harvest season in the Texas panhandle near the turn of the twentieth century—but this time, the filmmaker’s gaze upon them was not simply distant or ironic but positively cosmic. And there was so much more going on around these two characters, beyond even the dramatic triangle they formed with the melancholic figure of the dying farmer (Sam Shepard)—now the landscape truly moved from background to foreground, and the work that went on in it, the changes that the seasons wreaked upon it, the daily miracles of shifting natural light or the punctual catastrophes of fire or locust plague that took place . . . all this mattered as much, if not more, than the strictly human element of the film.

Above all, the radical strangeness and newness of Days of Heaven was signaled to its first viewers by its most fragmented, inconclusive, “decentered” feature: the voice-over narration of young Linda Manz as Linda, Bill’s actual sister, who is along for the ride, often disengaged from the main action but always hovering somewhere near. It might have seemed, at first twang, like a reprise of Spacek’s “naive” viewpoint from Badlands, but Manz’s thought-track goes far beyond a literary conceit. It flits in and out of the tale unpredictably, sometimes knowing nothing and at other times everything, veering from banalities about the weather to profundities about human existence. Sometimes even her sentences go unfinished, hang in midair. In this voice we hear language itself in the process of struggling toward sense, meaning, insight—just as, elsewhere, we see the diverse elements of nature swirling together to perpetually make and unmake what we think of as a landscape, and human figures finding and losing themselves, over and over, as they desperately try to cement their individual identities or “characters.”

In 2007 it was chosen to be preserved by the National Film Registry and Library of Congress for its achievement in being “culturally, historically, and aesthetically important.” Presently, Criterion is preparing to release it on Blu-ray, and I think if any film deserves such a treatment, it’s this one. This is a film I would have loved the opportunity to see on the big screen.

I can’t recommend this film enough. If you haven’t seen it, do yourself the favor of adding it to your netflix queue. I’m also sorry if this write-up is incoherent, like a lot of film critics, I have a hard time describing Days of Heaven because it’s that amazing.

Wow! This is quite interesting! I live in the Texas Panhandle! This looks like a great film too. Also the picture of the house in the winter looks like one of the house in my town! And it was built in the period of time too!

Thank you writing about a great film. The first time I saw the trailer it knocked me off my seat. The images really reinforce your point.

Jackie, I’d definitely recommend this movie, it’s BEAUTIFUL!

Joe, I’m so glad you like it! I think it’s an amazing film.

A lovely post about a lovely, mesmerizing film. I was lucky enough to see it in a theater, and I would hope everyone someday gets that chance. The spare acting went with the scenery – the view was three day’s ride in any direction, and swallowed the actors into the very depths of the visuals. I like it when films use the natural beauty of the real world as opposed to sets, and this film, along with “The Duellists”, (which had to willy and nilly, ’cause they didn’t have a budget for sets!) and “Letyat Zhuravli”(The Cranes are Flying), well, you could take every single frame and mount them as fine art in a gallery.

I watched this in a film class and I actually wasn’t that into it. But it is absolutely the most beautiful thing I’ve ever seen. It’s a great movie to watch with the TV on mute and a good CD on in the background. I’d definately recommend it based soley on that!

Also, I was told that it was shot during the ‘golden hours’ of the day, which is the hour before the sun rises and the hour before it sets. That must have taken forever to make.