Dear John: Remembering John Buckmaster

by Tanguy

John Buckmaster. The name sounds familiar to all those interested in Vivien Leigh. Wasn’t he the man making fun of Larry and his new mustache that first day at the Savoy Grill, when it is said that all really began? John Buckmaster. A name. A silhouette. Yes, now you see him better. But didn’t he turn totally mad in the end? Wasn’t he the one…? Yes, now you know. THAT John Buckmaster.

No matter how many biographies of Vivien Leigh you may have read, that’s all there is to it. John Buckmaster, stuck forever in that dramatic chapter. And when that one is closed, there goes John Buckmaster, back to obscurity.

And yet…

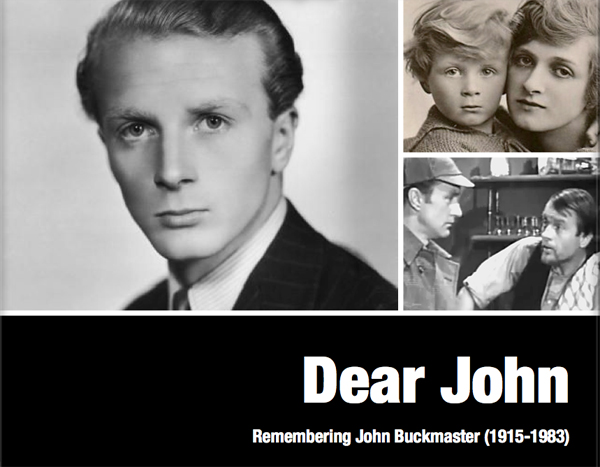

Posing in front of the camera in 1934, in a beautiful striped suit, exquisitely tailored, John Buckmaster was a vision of absolute elegance and beauty. He had the dreamy blue eyes of his mother – once the most photographed girl in London – and the manly bone structure of his father, with the spiritual nose and attractive mouth.

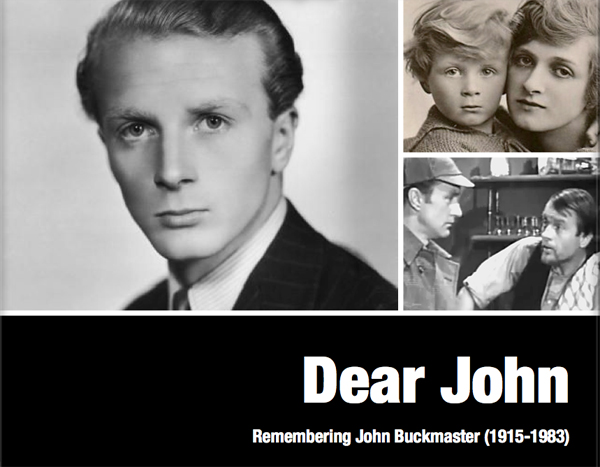

He was born on July 1915 to Gladys Constance Cooper – beloved actress and glorious beauty – and Herbert John Buckmaster, survivor of the Boer War; a great gambler and womanizer; a total black sheep; but a darling who kept in touch with his wife even after their divorce, giving lunch whenever she was in touch, arranging parties to celebrate her first nights, behaving less like an ex-husband and more like an intensely proud elder brother.

John must have loved that man who always behaved like a child himself, not hesitating to ride down from London to Charlwood on a pony to visit his children. There in a big Manor House in Surrey, John grew up in an enchanted world, sharing his life with several sheep, wallabies, a snake, a pet monkey, and a sister called Joan.

Several people with funny names came to visit. Mostly men, specially after his father left for the war. Ivor Novello, Raymond Massey, The Duke of Westminster. One day, Gerald du Maurier came by to have a glance at the menagerie. He was bitten by the monkey.

Beauty was everywhere — had to be everywhere. John’s mother had an issue with ugliness, illness, exhaustion and inefficiency. She couldn’t tolerate them and considered being less-than-perfect a mark of weakness to be fixed properly.

Accordingly, John developed the most elegant manners, the most delicate smile, and even took some boxing lessons with a friend of his father to improve his body and balance. One summer, when he was 9, he created a display and a cartoon was published in the Evening Standard. Both his father and mother got in touch with the cartoonist the following morning to buy the original drawing. In deep confusion, the artist wrote to Buck who replied, “It’s perfectly simple, dear fellow: I shall purchase it and you shall send it to Miss Cooper’s dressing room”. A kind of goodbye gift as the divorce became official in 1921.

It was not long before new items were added to the family menagerie. In 1928, John’s mother married Sir Neville Pearson, a handsome and titled baronet ten years younger than his bride. He was heir to a publishing firm and had just ended a disastrous marriage himself. John heard of their brief honeymoon in the south of France. Now studying at Eton, he must have felt a jealous sting as his mother seemed to have no trouble in taking on Pearson’s various stepchildren as her own. She seemed to take rather more interest in her new baby, Sally. She led a less mundane and active life than she had managed at the time of John’s birth, when the demands of her career were more exclusive.

Far from the imperious eye of his mother and not knowing about the cracks in the perfect mirror of her new, happy life, John faced adolescence alone. Sensitive, highly strung, extremely handsome and wittily talented, he couldn’t help but resent the man who had interfered with his close relation with his mother. He had taken an intense dislike to Pearson and it was reciprocal.

Had he known that after some sensual years the Pearson’s marriage was to turn to ruin, maybe John would have reconsidered his views. Later in life he would blame his eventual collapse on his mother’s inability to cope with him.

Out from Eton, with his looks, his talent, and his connections, he decided to start an acting career of his own. He played with Cedric Hardwicke, in Tovarich, settled in a little flat of his own in Chelsea, and started dating young and beautiful women, like Jean Gillie, and a certain Vivien Leigh.

According to Hugo Vickers, Vivien told Jack Merivale that John had been the first man she had an affair with after her marriage to Leigh Holman. In August 1935 they had spent a week end in Kent together. They shared youth and the love of fun and excitement. In short, they were made one for each other. According to his stepsister, Sally, Vivien was the love of his life. What would John’s life have been, had a certain Laurence Olivier not arrived on the scene?

Larry, was not a total stranger to John. In 1933, Gladys Cooper had secured the young unknown actor to play in “The Rats of Norway”. With her keen eye on youth, beauty and talent, she must have felt a certain attraction to young Larry, and according to him, showed nothing but kindness and generosity. So Vivien couldn’t have dreamed of a better escort to introduce them at the Savoy Grill, where Olivier and his wife, Jill Esmond, used to dine at the time he was playing “Romeo and Juliet.” The rest is history.

It must have been a cruel experience to see the woman of his dreams totally mesmerized by somebody else. But John had learned to hide his feelings and put on a happy face. On April 30th, 1937, Gladys Cooper, John’s mother, got married for the third time. The new stepfather’s name was Philip Merivale, a 47 year old English actor and widow of Viva Birkett, by whom he’d had four children. This time, John decided to smile. Not only did he put up with his new family – among which was a stepbrother named Jack Merivale – but when his mother decided to tour America with her new husband, he decided to come along. In 1938, he played on Broadway in a Dodie Smith family comedy, “Call it A Day”. Handsome and already accomplished as an actor, he seemed destined for a brilliant future. He decided to forget the Pearson episode, got on well with his mother, and also took kindly to Philip Merivale who wanted nothing more than the fusion of the two families. After “Call it A Day”, and flattering appearances in all the best gossip columns of New-York, he accepted the part of Lord Alfred Douglas opposite Robert Morley’s Oscar Wilde. Off stage, he seemed to have found in America a place to suit his ambition and sense of adventure. He started writing songs and made quite a name for himself in cabaret. But life decided to play another trick. War broke out in September 1939 when he was just 24.

“Phil says John is doing very well in cabaret at the Algonquin and though people keep writing to me from England saying that he should go back and fight with the others, I really haven’t the heart to persuade him to give up his New-York life…” So wrote Gladys Cooper just after seeing Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh back to England in 1940. Although nothing is certain about his state of mind at that stage, one can assume that the pressure on John was intense. He felt split between his mother’s will to keep him close and safe, his own guilt at letting his friends go, and leading a secure life. In July 1941, Gladys wrote again: “John has decided to go home and fight; though it frightens me I think this is probably for the best”. John’s stepbrother Jack Merivale had married a young actress called Jan Sterling had decided himself to enlist in Canada. The Farewell Party took place in Central City, Colorado where John was appearing in a very successful show of his own. His mother was surprised to be presented for the first time as “John Buckmaster’s mother”.

It would be four years until John went back to California. He was on leave and met his stepbrother there. It was the first time Jack Merivale noticed the inner tensions of his relative and the distinct uneasiness in John’s relation with his mother. “I shall never forget her coming back that time from England and looking at us all in the house and saying, ‘You must all have had a lovely time – everyone does while Mum’s away’ – and then another morning John and I were standing in the drive watching her drive off somewhere and suddenly John breathed a great sigh of relief and said, ‘Whenever I’m with her, I feel I’m always doing the wrong thing, whatever it is’. That was her own son, whom she adored: she was curiously unable, I think, to make even those she most loved feel that love very often.”

When Philip Merivale died of a heart ailment in March 1946, Gladys reacted as she always had, by turning her mind on something else. She threw herself back into work and decided to do it in a revival of Lady Windermere’s Fan with a cast including her own daughter, Sally, John and Jack. They opened in California and then travelled to Broadway where they played the 1946-47 season. At the end of that run, Jack and Sally returned to Gladys in California, leaving John to stay with friends in New-York. It was then, via a phone call, that Gladys learnt her son had suffered the first of many mental breakdowns which were to become a regular and increasingly violent part of their lives for the next ten years.

“There is neither the place nor the expertise here for an analysis of that condition”, wrote Sheridan Morley in his 1979 biography of his grandmother, Gladys Cooper. “Briefly: the strains of a war in which he’d felt himself perhaps involved too distantly and too late, of a number of increasingly unhappy love affairs, and of maintaining a career which had began with rather too much glitter and not enough training, were proving too much for John, and under those pressures and the other pressure of being Glady’s son he was now, slowly but surely, to crack – temporarily at first, then for longer periods…”

What is sure, is that his mother could never bring herself to fully accept that her only son was mentally unstable. Invariably, she would refer to his condition as “flu”, even when shock treatment were necessary to contain his acutely schizophrenic condition. Mental illness – however sad it is – was for her a sign of weakness, something to be ignored and overcome rather than treated.

John Buckmaster, from then on, was on a series of highs and downs. The smiling boy with the golden curls turned into a haunted spirit, more and more dependent on drugs and treatments and trying hard to keep up with the gentle and perfect silhouette his mother wanted him to be. At her Pacific Palisade home in 1947, he is a short sleeved young man, sitting by a little table under the porch facing the swimming pool. Five years later, in New York, he will be chased by the police to Park Avenue and 75th Street, accused of molesting women, and arrested in possession of two kitchen-type knives. Sent to Bellevue Hospital for psychiatric observation, he was admitted one month later to the state hospital at Kings Park, Long Island. Jack Merivale and Noël Coward took action to have him sent back to England on the condition that he went into treatment there and never return to the New York state again.

It was but one year later that he reappeared in Hollywood in one of the most dramatically written episode in all the Vivien Leigh biographies.

Little is know of the relationship John Buckmaster managed to keep with Vivien after she met Laurence Olivier. Larry must have resented the vicinity of Vivien’s old flame. But one can’t imagine Vivien – even for the sake of her love – giving up such a funny and handsome partner. She had always been faithful to the people who had been close to her and one doesn’t see why it would have been different with John. Besides, she had always been a great admirer of John’s mother. Gladys Cooper, in her eyes, remained the greatest beauty of her time. And when she came to California to film Gone With the Wind she made sure to keep in touch with John’s mother, now an eminent part of the group of British exiles in Hollywood. They must have met on Sundays when there was cricket on the lawn followed by a tea party. One corgi had some lovely puppies and Gladys decided to call one Scarlett, “because she looks just like Vivien and is very tempestuous”.

Larry and Vivien had also been acquainted with Jack Merivale, who had joined the cast of “Romeo and Juliet” to play the bit part of Balthasar. John must have heard about the news with mixed feelings. The more he tried to get away from Vivien, who was now happily married to Larry (“at last” his mother had written), the closer she seemed to get with the rest of his family. Missing the opportunity to act with Larry and Gladys in “Rebecca”, Vivien got her revenge in Korda’s Lady Hamilton, where John’s mother played the stern figure of Lady Nelson.

So, despite the years passing by, the link between Vivien and John had never been broken. After all, they had been young together, and shared the same expectations of a glorious future and perfect tomorrows, until war and reality cast their black shadows. The set of A Streetcar Named Desire, where John visited one day in Hollywood, was the proper place for a reunion. One can imagine their mutual state of mind, both by now having a history of mental illness. Once they had been partners in fun and laughter. Now they started mentally to drift away, nourishing their inner monsters with the cruel knowledge that no one really understood them. In these doomed circumstances, Vivien would be luckier in a sense. She had a husband, friends, family who fought for her and who tried desperately to build a wall between her illness and the world. John had nothing of the sort to protect him against the morbid curiosity of the press. His name was splashed across the pages of magazines, no longer in the elegant gossip columns but under the most frightening titles: “Felonious assault”, “Concealed weapons”, “Sent to State Hospital”. Then Vivien’s nightmarish breakdown happened in 1953, leaving readers with the image of John Buckmaster as a tragic and grotesque figure; soon to be removed from the set dressed in a towel, tearing up money, and asking Vivien to fly out of an upper window with him.

The little boy with the shy smile who had posed in so many happy photographs in town, in the country, even at the beach, seemed to have torn apart the family album. He bravely attempted to revive his acting career in the years to come, appearing briefly in some episodes of Sherlock Holmes for television; playing bartenders and butlers; a thin figure, still handsome, with a funny accent. He refused to see either of his parents, both of whom he blamed for his breakdowns, before settling into the clinic where he would live out the latter half of his life. Did he hear about Vivien’s fate? Larry made sure, after the 1953 episode, that they never got in touch again. John must have heard of the divorce, and of Jack living with Vivien. Such irony. And then, little by little, they were gone. Vivien first, in 1967. Then his mother, in 1971, from lung cancer. Approaching 70 she had started learning to type but had left when the instructors objected to the length of her fingernails. What couldn’t she do besides making her son happy and healthy? The world which had been such a funny place then turned to a big black shadow, place which no longer interested little Johnny. It was there, in the Priory, that he committed suicide on April 1, 1983.

He was 68.