The Old Vic Company with Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier has given the New Theatre the national character of Drury Lane in Nell Gwynne’s Day

News Review

February 10, 1949

This evening (Thursday) the Old Vic has another first night at the New Theatre.

After a curtain-raiser – Anton Chekhov’s Proposal – the serious business of the evening will begin: Jean Anouilh’s modern dress version of Sophocles’ tragedy, Antigone, with Vivien Leigh as the highborn Cadmean maid and Laurence Olivier as Chorus.

At first by purring beauty, but increasingly by merit and then by marriage, Vivien Leigh has become part of the finest theatrical constellation in the world.

“I’ve been awfully lucky,” she said thoughtfully last week, adding with a laugh: “I’m half-waiting for some blow to fall.”

At 35, Vivien Leigh is a star by technique, and some say by temperament. But none of the quirks of a prima donna accompanied her quiet insistence on a softer lace cuff when she was being costumed for Sheridan’s Lady Teazle. Miss Flora Campbell, of Hardy Amies, in Saville Row, where she gets most of her clothes, thinks “she’s delightful to deal with.”

Petite, she weighs 8 stone, has 34-in. bust, 22-in. waist, 35 ½-in. hips. Miss Leigh drapes her 5 ft. 3 ½-in. in voluminous mink (“Call is sable. I won’t mind”), in which she sparkles like a white diamond. There are red lights in her hair, green lights in her eyes.

She was born in Darjeeling, India, on November 5 1913, and was christened Vivian Mary. Her father, Ernest Richard Hartley, was an English stockbroker of French descent; her mother, Gertrude Robinson Hartley, was Irish.

Wherever they went in those first five years they took young Vivien. But in 1918, a sensitive, imaginative child, she was boarded in at Roehampton’s Sacred Heart Convent, where she carried the fairy’s wand in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Only Vivian seemed to realize history had been made. She solemnly announced her intention of becoming a great actress. ‘I can’t remember ever wanting to be anything else.”

Fame is the Spur

All through her finishing in Paris, San Remo and Bavaria, her enthusiasm was for the stage, dancing and elocution. She studied dramatics with Mademoiselle Antoine of the Comedie Francaise, in Paris: at 16 she entered the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art.

Vivian Hartley was 19 and Herbert Leigh Holman was just starting his career as a barrister when he met her at a county hunt ball. Two years after they married, Suzanne (now 15) was born.

But fame was still the spur. Vivian ran her home by remote control, went back to RADA, to voice production at Elsie Fogerty’s, and singing with Baraldi.

She altered a vowel in her Christian name, took her husband’s middle name, and became Vivien Leigh.

Since her first role as a spindly-legged schoolgirl in a British film Things Are Looking Up, Vivien Leigh has played every part she could lay her tongue to. Her first stage part was in The Green Sash, at the “Q” Theatre, Richmond.

On May 15, 1935, Sydney Carroll starred her as the wanton Henriette in The Mask of Virtue.

“I was in Fleet Street at 4 am to see what the critics said,” she admits. Every notice was a rave, though the more discerning agreed that it was her saucy, wispish beauty rather than exceptional acting ability that had won her plaudits.

Whatever it was, Vivien Leigh was in – with a five-year £60,000 film contract from Sir (then Mr.) Alexander Korda.

For three years she appeared in stage and screen roles “no one of which,” wrote one critic, “was good enough to stamp her as a star, nor bad enough to suggest she had nothing to offer but her looks.

She played the queen in a Gielgud-directed Richard II, Anne Boleyn in an outdoor Henry VIII, and Ophelia to Olivier’s Hamlet in Denmark in 1937.

As a lady-in-waiting to Flora Robson’s Elizabeth in Fire Over England she was wooed with more sincerity than the film demanded by Olivier.

She was flirtatious in A Yank at Oxford, mean and unscrupulous as the Cockney girl in St Martin’s Lane. She was vixen, bewitching, artful. Always she was beautiful, seductive, feminine.

The Georgia Belle

Two things took Vivien Leigh to Hollywood in 1939: love of Laurence Olivier and an obsession to play Scarlett O’Hara in Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind.

“I’d read the book long before,” she said. “I would not have gone to Hollywood for any other part,” and in her eyes and her voice there was a glint of the lovely, unscrupulous Georgia belle she brought so memorably to the screen.

For that “flawless” performance she received the ovation of the critics, that acclaim of the public and the 1939 Academy Award.

When Olivier produced Skin of Our Teeth, Thornton Wilder’s comic strip history of mankind, Vivien ignored “friendly” advice to drop the role and fought David Selznick in the High Court for release from her film contract.

“Long contracts are stultifying,” she declared. “I only signed that one because I had to, to get Scarlett.”

Written and staged with eccentricity, Skin of Our Teeth proved a gem of a play, and Vivien Leigh, whether as the servant girl, beauty queen or vivandiere, gave a performance of “diamond brilliance.”

Illness interrupted the run in July 1945. For 12 months Miss Leigh nursed a spot of lung trouble in the Highlands, Bucks and New York. By June 1946 she was back in the West End.

“I’m completely well again now,” she said, adding with sincerity: “Everyone was so kind, even out in Australia.”

The nine months’ tour which the Old Vic made to Australia and New Zealand last year was one long triumph.

“It was wonderful,” she said, re-catching some of the excitement. “But it seemed a pity to go such a long way and then not see more of the country.”

Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier were both already married when they met. Their divorces became absolute in America on the same day in August 1940. Later than month they were married in Santa Barbara, California.

At the new, their dressing rooms – hers No. 1 with a brass nameplate, his No. 2 – are side by side, just off-stage to the right of the auditorium.

“I don’t know where you can sit,” she said, when News Review came to visit her last week, and quickly whipped some things aside. Couch and chairs were “hung” with the stuff stars are made of.

“That’s ‘New,’” she said of the only photograph there – her much-loved Siamese cat, named after the theatre. “He was run over outside Notley [their place in Bucks]. Now I have ‘Boy.’ I had 16 cats once.”

There were bowls and bowls of flowers – red tulips, daffodils, narcissi and white lilac.

“I love white flowers – syringe, lilac,” they must have perfume.

“Don’t look at my nails,” she begged, as she picked up her teacup. “They’re all broken. It’s the polish. I have to change it so often – pale for Scandal, bright red for Skin of Our Teeth – the shade depends on the play.

“No, this is the first time I’ve played Antigone,” and an afterthought, as she lit a cigarette, “My favourite Shaw play is Saint Joan. Don’t you smoke? I wish I’d never started.

“Doing a new play every two nights is exciting and stimulating. I dislike long runs – they’re nerve-racking – quite a different sort of nerves from first-night nerves – and I find I can’t remember my lines.

“What I like best of all is to do stage and films. But I hate getting up, and films start so early. If I’m making a picture I have my bath at night, and I’m out of the house in 15 minutes dead from being called. If I allow more I’m always late. Larry’s just the opposite. He takes hours to wake up.”

The old Vic demands everything of its players. By the time the Oliviers push open the yellow gate in the high brick wall which secludes their Chelsea home, fans and fame are fighting a losing battle with bed.

Durham Cottage, just off the King’s Road, might well be the doll’s house Walter de la Mare created for his Midget. There is a tiny would-be lawn. An old iron lamp hangs outside the pale yellow front door.

Stars on Earth

The French windows from the lounge open on to a little flagged yard with a miniature lily pond, a trickling fountain and an old stone lovers’ seat.

Whatever Lady Durham’s grooms used the glass-roofed lean-to for in their day, it is now the Oliviers’ attractive, papered dining room – gay glazed chintz curtains, shelves of royal blue and green glasses, a gastronomical map of France, dark chairs with lime-green cushions piped with cherry.

When the Oliviers entertain it is more often Larry and Vivien than as Sir Laurence and Lady Olivier (“I don’t mind which I get, really. I get Vivien Leigh mostly – and I like it”).

Four, perhaps six, guests will sit at the round, veneered table. The chances are they will have any one of Lobster (shrimp or prawn) a la Newburgh, Mimosa Eggs, or a hot soufflé.

“I really love French and Italian cooking – oily foods,” said Vivien, who plans the meals. “She likes anything cooked in wine,” said Owen Jones, who does the cooking, ad keeps a list of old favourites scribbled down in a shorthand notebook.

Like her dressing room, the house is generally full of flowers – freesias, red roses, lilac, tulips – some of them theatre tributes.

Mental, rather than physical exercise appeals to Vivien Leigh now.

“I used to ride and golf, but gave it up. Most of my reading is play-tasting. I love The Times crossword – I do it every day, and I get it out sometimes. I like all card games, too.”

Music in the Olivier home comes from the gramophone.

“I learnt the violin and cello, once – at least I sat up in the back and plucked the string occasionally, but now I like the piano.

“I adore dancing, even watching it,” she declares with intriguing emphasis on the second word – a trick she uses often in animated conversation.

Up the sharp about-turn staircase carpeted in bright blue is a small study where Mrs. Phil Davies looks after Vivien Leigh’s affairs (and Mrs. Dorothy Welford, Olivier’s), a maid’s room, the Oliviers’ bedroom, papered in pale grey-green with a satin polka dot, and a white-walled bathroom fitted in musk pink.

The only photo of either of them about the house is one of Olivier on the glass-topped dressing table which runs the width of the bedroom, under the windows.

A Yen to Paint

Arranged before the mirror is Vivien Leigh’s perfume shop, a crescent moon of fascinating bottles, expensive names and exciting perfumes. Among them: Caron’s Bellodgia and Tabac Blond, Worth’s Jans la Nuit, Marcel Rochas’ Femme. There is Revlon Bachelor Carnation nail polish and some Peggy Sage.

Like polish to plays, perfumes are to occasion and dress. She wears a lot of black, with lovely jewelry.

“I love French greys and blues, pale yellow and musk pink.

“I liked the rounded shoulders of the New Look, but some of the lengths were silly.” Miss Leigh has most of her clothes 11 or 12 inches from the ground, but she conceded a little to fashion on the last – it was only 10 ½.

Next to quiet evenings at home, a few special people, the Oliviers like best to snatch some time and get away to Notley Abbey, Bucks, the 16th century abbey which Olivier bought a few years ago, and which has since become a theatrical museum of plays, costumes, props and model stage sets.

“We like to motor down every weekend if we can. No, I used to drive, but not now.”

It is at Notley that the young Oliviers spend their holidays. Vivien’s pretty, fair-haired daughter Suzanne (“She’s wearing a fringe at the moment”) dotes on the place. She also dotes on horse riding.

Olivier’s 12 year old pianist son Tarquin (“The name came to me in a mad moment,” he says happily. “It has such dramatic overtones”) is darkening up like his father. At present he is at school in Cottesmore.

“We are both going to take up painting soon, as a hobby,” said Vivien. “No, it wasn’t entirely Churchill’s article, although I thought it was wonderful, and I do want his book. A lot of our friends paint, and we would both like to try it.”

I see small inconsistencies in this article from the facts I had understood about Vivien: this article says her mother’s maiden name was Robinson and not Yakjee, and that Vivien’s daughter was born 2 years into her first marriage and not within the first year.

Excellent observation! What you picked up on is the manipulation of facts that occured when generating a star’s public image. The real Vivien Leigh was somewhat different from the Vivien Leigh the public saw and read about. And yet they were one in the same, if that makes sense. Usually the studios worked to create a public persona for their talent. In Vivien’s case, the details about her father being French and her mother being Irish were fabricated by the publicity team at Selznick International to make her appear more like the fictional Scarlett O’Hara in 1939 (Robinson was a real family name that Gertrude Hartley apparently used quite often, although her real maiden name was Yackjee). She underwent a similar process with Korda in Britain in the 1930s.

If you sift through the article database, you’ll likely come across several pieces of reportage that offer facts about Vivien’s life with varying degrees of accuracy.

This was a great article. Thank you so much for sharing it:) I thought Notley Abbey was 13 century.

Thanks for sharing, Kendra, very thoughtful of you! By coincidence, I’ m re-reading Walker’s biography;the article describes the Olivier’s legend (including what Norman Mailer would call factoids) just at the time when their happiness together, their union (and eventually their marriage) was beginnign to collapse.

Very sad to view in retrospect but very interesting

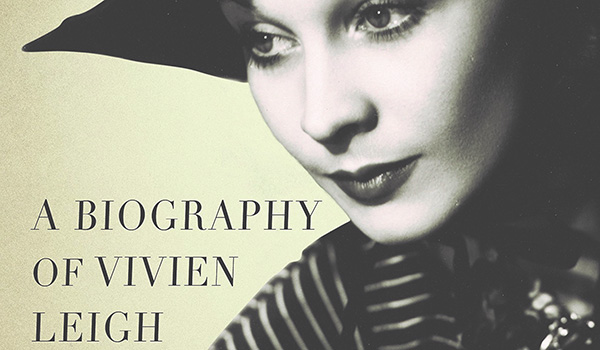

I enjoyed both the photograph and the article, Kendra. Thanks for posting them.

This was the period when Irene Selznick and Tennessee Williams went to London in preparation for the production of “Streetcar” across the pond. Here’s what 10 wrote to his friend Donald Windham in a letter dated May 8, 1949:

“I have been to the theatre every night and matinee. Nothing new is good but the Old Vic is doing a magnificent ‘Richard III’ in repertory. Vivien Leigh is not really good in ‘Antigone’ but I have a feeling, now, that she might make a good Blanche, more from her off-stage personality than what she does in the repertory, though she is quite good in ‘School for Scandal’. She has great charm. Sir Larry is a bit on the grand side, but today he let his hair down and we became chummy. They live in an old abbey that dates from the thirteenth century. Danny Kaye, who is the rage of London, was present but was extremely quiet. Larry acted continually, even imitating the horses in ‘Henry V’ which he did amusingly and Vivien was extra sweet to Frankie, which pleased me even more than it did him.”

A well-written article. 🙂

I don’t know what to say other than there is something definitely Indian about this woman. She doesn’t look or behave purely English from that era. Her eye movements, wavy hair, facial curves and body movements are too much like someone from the subcontinent. Given that the English right till the 70s never let their children adopt any “native” mannerisms especially the colonials, and that mixed people who could cross the line did and hid their mixedness as much as they could, I really am wondering if this woman has no mixed blood at all. PS I grew up in that era