by Vivien Leigh

Everywoman, April 1951

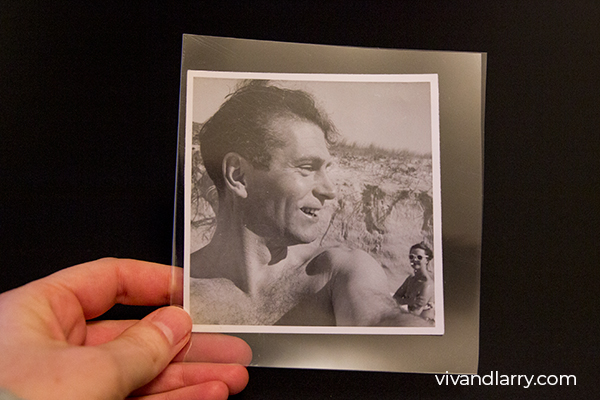

*NOTE* The images below were published with the actual article, but these original prints by Tom Blau were scanned from Vivien Leigh’s personal albums, part of the Kendra Bean Collection.

The snag in success is that the nearer you get to it the farther away you feel yourself to be. The world may call you successful, but in your heart you know that you never fulfil your own hopes. Which is perhaps all to the good, for complacency is a fatal state, though a very pleasant one, if you can remain in it. I never can.

Whenever I let myself feel thrilled and flattered by the approbation of other people self-criticism rears itself, like a snake, at the back of my mind and destroys the illusion. I think this is partly due to the fact that I arrived at the top too soon, and too easily, instead of by the hard way, like Larry and so many others. It all happened — literally — overnight; a dream that left me rubbing my eyes and saying: “This just can’t be true” but with the fixed determination to never allow myself to be deceived by it into letting up on my own standards. Not even Larry, who is merciless as a producer [director], has ever criticized me as candidly as I have criticized myself.

So that is the first and most important lesson that success has taught me: to beware of self-satisfaction.

Scott Fitzgerald, who is one of my favourite authors, says: “The compensation for very early success is that life becomes a romantic matter.” I have certainly found it so, but perhaps I was biased by an Irish mother, who was blessed with an imagination that could turn ordinary, everyday happenings into an exciting adventure, and make you feel that there was always something wonderful waiting just around the corner. She created a dream world for me, filled with so many imaginary people that, although I am an only child, I never knew the meaning of loneliness.

I was born in one of the most romantic places in the world — Darjeeling — although I have only confused impressions of its beauty, and of the gaiety of life there, for my father, who was a stockbroker, brought the family back to England when I was five. After that the process of my education began, first at the Convent of the Sacred Heart in Roehampton, and later on the Continent.

I can scarcely remember when I first thought of going on the stage, because it was such an accepted fact of my childhood. I never even imagined myself in any other career, and as I was fortunate enough to have understanding parents all my education and early life were shaped to that end. So instead of being harassed over the weakness of my mathematics — apparently to this day — I was allowed to specialize in history, literature, and music, and to study languages abroad.

My father and mother loved to travel, so we spent far more time wandering around the Continent than in England. I was sent successively to schools in France, Italy, and Bavaria, and this erratic education was a great help afterwards.

Apart from the fact that I learnt to speak several languages more or less fluently, and had the opportunity of studying diction and the theatre in many countries, I met people of all types and nationalities. They gave me that flexibility of mind which is so necessary which is so necessary to an artist, and taught me, I hope, understanding. Through knowing them I have always been able to recognize the characters I played, and love them.

Eleven-year-old-fan

In the summer we generally went to Ireland, or to the English Lakes. It was while we were staying in the Lake District that I met my first love in the theatre — George Robey.

I was already an ardent fan, even to the extent of having seen him in Round in Fifty no less than sixteen times, and when I discovered him seated at a table in the dining-room of our hotel, prosaically putting away a big plate of eggs and bacon, I could not take my eyes off him. In the end my unblinking stare caught the attention of his wife, Blanche Littler, who was sitting by him, and she nudged his arm, looked in my direction, and whispered something. He turned, and favoured me with a broad smile that almost took my breath away, and a moment later — oh, joy of joys — the two of them stopped at our table on their way out of the room! I was so overcome with emotion that I could only murmur: “I adore you.”

Probably he was familiar with the adoration of eleven-year-old fans for his reaction was prompt and practical: “Would you like one of my photos?” And without waiting for my ecstatic reply he dived into his pocket and took out, not one, but ten photographs of himself, all of which, with the kindness and generosity so characteristic of him, he put into my eager hands.

I began my training for the stage by studying in Paris under Mlle Antoine of the Comedie Francaise. She was a most inspiring teacher, and I owe a great deal to her care in correcting my diction, and to her encouragement.

“I believe you have a future in the theatre, mon enfant,” she told me, “but you must go back to England and work…work…work. If you do that I shall see the name Vivian Hartley in big letters outside a London theatre one day. I promise you.”

But lives are not so easily planned. What actually happened was that I went down to Devonshire to stay with friends, met a barrister from London, and Vivian Hartley became Mrs. Leigh Holman.

I was under nineteen when I married, and not quite twenty when my daughter was born. I felt too young to be the mother of a child, and very lacking in the qualities of restfulness and serenity which a mother should have. How many times since then Scarlett O’Hara’s line, in speaking of her mother, have sprung to my mind! “I always wanted to be like her, calm and kind. I certainly have turned out disappointingly.” But I was not cast in the mould of serenity, and in any case, although you may succeed in being kind at twenty you cannot be calm, with all your life still before you, and your ambitions unfulfilled.

I loved my baby, as every mother does, but with the clear-cut sincerity of youth I realized that I could not abandon all thought of a career on the stage. Some force within myself would not be denied expression. I took the problem to my husband and asked his advice. he was many years older that I was, a deeply kind and wise man, with that rare quality of imagination that implies tolerance and unselfishness, he met me with complete understanding. We decided that I should continue my studies at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. We took a tiny house in Little Stanhope Street and got a good nannie for the baby.

Luck paved the way

I left R.A.D.A. at the end of my training, only one of many aspirants to the stage and films, and with still a lot to learn. Like everyone else I dreamed of an immediate engagement in the West End, but all I got was a succession of small and unimportant parts in films.

But in one respect I was lucky, and here I must say I believe luck — sheer luck — is a tremendous factor in success. A sheltered home life, and a husband who bore the brunt of the battle, made the way so much easier for me than for many others. If I had not had that support my story might have been a very different one, and I admit it with humility. I do not know how I should have stood up to hardships and persistent setbacks. I can only be thankful I was not put to the test.

I made my first appearance on the stage at the Q Theatre as Guista in The Green Sash. I am sure I was not good in the part, which was a long one and far too difficult for anyone as inexperienced as I was. But Charles Morgan — the only critic who turned up on the first night (God bless him) — gave me two, not too scathing lines in The Times, with the result that Sidney Carroll was interested, and came to see me in the part.

As it happened he was just then planning the production of The Mask of Virtue and looking for someone to play Henrietta. He asked me to come in for an audition. I can still remember my excitement when I went along for it, and my absolute despair when the actual moment arrived. When Sidney Carroll handed me the script and asked me to read the part I literally shook with fright. But Lilian Braithwaite, who had been invited to the audition, gave me a smile of friendly encouragement, and somehow I managed to find my voice.

After I stopped reading there was a moment’s silence. Then Lilian Braithwaite said briskly, “I think we have got the right girl, don’t you, Sidney?”

The miracle happens

The play opened at the Ambassadors in May, 1935. I remember looking up, with an emotion nearer panic than satisfaction, and seeing my name in big letters outside the theatre for the first time. Not Vivian Hartley, as Mlle Antoine had once prophesied, but Vivien Leigh, the stage name I had taken at Sidney Carroll’s suggestion.

It was a romantic first night. I had a part that was both good and decorative, and I was helped by the entire cast, with that wonderful loyalty and generosity of the theatre world towards a newcomer. The fact that I was young and unknown caught the imagination of the audience. The roar of applause when the final curtain fell told me that the miracle had happened. I had arrived.

Of course I was flattered, but even so I realized that success had come to me before I had earned it, before I was able to shoulder the responsibility. Some commonsense streak in me kept me from having my head turned, made me understand how easy it would be to slip, unless I compensated for my lack of experience by hard work. I struggled far more to keep at the top than to get there.

I appeared in several productions: in John Gielgud’s beautiful revival of Richard II for the O.U.D.S.; in The Happy Hypocrite, with Ivor Novello; in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Old Vic, where wonderful Lilian Baylis alternately cajoled and scolded all of us into fulfilling the traditions of her beloved theatre.

The one evening the whole course of my life was altered.

I was having dinner with a friend in the Savoy Grill when, in the middle of the conversation, he looked across at another table and said: “Doesn’t Larry Olivier look odd without his moustache?” For some inexplicable reason I flared up! I had seen Laurence Olivier not long before in The Royal Family and had been one of his fans ever since (I still am, for that matter). And anyhow, I didn’t think he looked at all odd.

After supper we were introduced. It was not a very romantic meeting, and I am not sure that it was even love at first sight. It was not until later, when we acted together in the film Fire Over England, and in Hamlet at Elsinore, that we realized that there could be no happiness for us apart. But for a long time the discovery brought only sadness and unrest, for we were not free to marry.

The Christmas of 1938 will always stand out in my memory, for it brought the fulfilment of a cherished dream. I have always believed that if you want something with all your heart and soul you get it.

From the moment I read Margaret Mitchell’s novel, Gone With The Wind I was fascinated by the lovely, wayward, tempestuous Scarlett. I felt that I loved and understood her, almost as thought I had known her in the flesh. When I heard that the book was to be filmed in Hollywood early in 1939 I longed to play the part, but just at that time I was going to appear in the revival of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which Tyrone Guthrie was producing in the Christmas season. As I had a few weeks before rehearsals began I decided to fly to Hollywood where Larry was making Wuthering Heights.

When I arrived there everyone was talking of Gone With The Wind, on which David Selznick had already started production — without a Scarlett. Dozens of people had been tested for the part, but no one had been chosen.

Myron Selznick took me out to the studio one day to watch some of the scenes being shot. His brother David joined us. Myron introduced him. “David, I want you to meet Miss Scarlett O’Hara.” David grinned. “Would you like to make a test?”

So I joined the queue. There were so many of us being tested that the dressers scurried to and fro getting us in and out of Scarlett’s clothes. As soon as you took off one dress someone else put it on. You had a few minutes in front of the camera, and then it was the next girl’s turn. It was all rather discouraging; I felt that I had not much of a chance. When Larry and I went to spend Christmas Day with George Cukor, who was directing the film, I made a resolution to talk of anything but Gone With The Wind. But George himself brought up the subject. “Well, I guess we’re stuck with you, Scarlett.” And I knew that my dream had come true.

Best-loved roles

Scarlett has always been my favourite film part, although I have loved others, too, especially Lady Hamilton, in which Larry played Nelson, perhaps because it was the first film we made together after our marriage in California. One the stage the part of Sabina in Thornton Wilder’s The Skin of Our Teeth has appealed to me most of all, and I found her a real joy. Another character who gripped me, though in a very different way, was the pathetic Blanche Du Bois in A Streetcar Named Desire. So many people have condemned the play for its sordid theme. To me it is an infinitely moving please for tolerance for all weak, frail creatures, blown about like leaves before the wind of circumstance.

Sixteen years have passed since that first night of The Mask of Virtue when success came so suddenly that I distrusted it. I do still, but it no longer seems so important, for I have learnt many things since then. One is that to live in the fullest sense is worth more than to attain any material reward.

In looking back on the past I realize that the memories I cherish most are not of first night successes, but of simple, everyday things: walking through our garden in the country after rain; sitting outside a cafe in Provence, drinking the vin du pays; staying in a little country hotel in an English market town with Larry, in the early days after our marriage, when he was serving in the Fleet Air Arm and I was touring Scotland, so that we had to make long treks to spend our weekends together.

I have learnt too that love is the greatest gift that life can offer, and that no price could ever be too dear to pay for it. I have grown to appreciate friendship, while remembering that it has obligations, and that it you want to receive it you must cast your bread upon the waters freely.

I believe sincerity and a fixed aim are essential to success, and that the greatest assets you can bring to a marriage, are imagination and a sense of humour. Most of all, I have learnt to say, from the bottom of my heart, that I would gladly live every moment of my life again.

What a wonderful article. Loved reading every word. Thank you so much.

Thanks for reading 🙂

Love the article. Thank you so much for your work. You know, I always loved GWTW. But really knew very little about Miss Leigh or her background. It was fascinating to read how cutting edge GWTW in how it was filmed. It is an absolute classic that many of us are still discussing eighty years later. It is still considered in the top ten of movies in cinema, EVER. I have enjoyed finding out about it. I just recently really found out through a VL biography and through your work of VL and Olivier. Always thought she ended up alone; never knew that she had Jack Merivale in her life at the end. I really, really enjoyed the story about Tickeradge Mills, and the lovely photos. Loved it!

Kendra, I have two questions for you. Do you know if Tarquin Olivier has any kind of relationship with his half siblings, from Olivier and Joan Plowright. Also wondered if Jack Merivale was interviewed about his time with the late, great VL. He seemed like he really cared for her. Seemed like a really good man that was attentive to her. Thanks again!

Hi Teri,

Thanks for the comment. I’m not sure how close Tarquin is with his half-siblings. He’s quite a bit older than them. Jack Merivale graciously gave interviews about his time with Vivien to various biographers, including Hugo Vickers and Anne Edwards. By all accounts he was a good person.