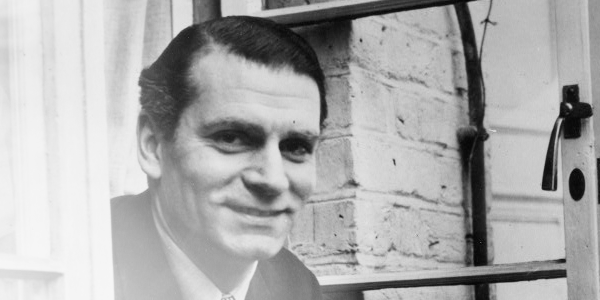

In the 1960s, Laurence Olivier successfully bridged the gap from studio films to the British New Wave with his performance as Archie Rice in the 1960 Tony Richardson film The Entertainer. Two years later he continued his string of “ordinary” characters by playing Graham Weir in Peter Glenville’s Term of Trial, which was screened at the BFI last night as part of their Projecting the Archive series. Jo Botting, the curator of fiction at the BFI archive, gave an introduction before the film. She read excerpts from Sarah Miles’ autobiography and talked about how the film was received upon its initial release.

Term of Trial is one of Olivier’s lesser-known films and, much like in William Wyler’s Carrie (1951), he delivers a quietly powerful and underrated performance as an alcoholic school teacher in gritty northern England who becomes the object of one of his female students’ affection. Graham Weir, despite being a genuinely nice man who wants to change students’ lives for the better through his teaching, is accused of sexual assault when he rejects the advances of young Shirley Taylor (played brilliantly by an 18 year old Sarah Miles in her first film role), his prized pupil. Shirley is so enraged and hurt by Mr. Weir’s rejection that she brings false claims against her once revered teacher. Graham is in a lose-lose situation all around. At home, his nagging, selfish wife (Simone Signoret) accuses him of not being man enough to give her the life she thinks she deserves. He is frustrated at school by the defiance of a trouble-making student (Terrence Stamp), and the accusations brought against him cost him the coveted job of head schoolmaster.

It seems that many people found–and still find–Olivier miscast as Weir, but I thought it one of his best performances. Subdued yet sympathetic throughout most of the film, Olivier the great stage actor breaks free when he is given full reign of the scene when Graham stands accused in court. All of his sublimated emotions and frustrations suddenly explode (we get a glimpse of something boiling beneath the surface in a previous scene when his wife’s comments cause him to violently slap her across the face). Paul Dehn, critic for the Daily Herald said of Olivier’s performance in the courtroom scene:

“Olivier’s own long speech from the dock is a piece of inarticulate agonising as unforgettably delivered as the best of his Shakespearean soliliquies.”

I urge anyone who mistakenly accuses Olivier as being nothing but a hack or ham actor to reconsider his performances in this film as well as in Carrie.

Term of Trial has an all-around strong cast. Simone Signoret was, as always, tough as nails. I had the opportunity to see Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques the previous evening and was blown away by her performance as a school teacher who helps to murder her colleague’s headmaster husband (with whom she was also having an affair). Sarah Miles was surprisingly very good as Shirley and more than held her own opposite her acting idol. Miles also claims to have had an on and off affair with Olivier that started during filming and lasted for several years. I had only seen her previously in David Lean’s Irish epic Ryan’s Daughter and didn’t think much of her at the time; my mistake. Terrence Stamp (also in his first film role) plays the thug character to perfection, the incarnation of so many angry young men of the period.

What I love about Olivier was his ability to develop his acting style through different filmic periods. From matinee studio idol to Shakespearean expert, everyday average Joe to supporting player in later years. It’s always a pleasure to see the range of his film acting. There are people who insist he was best on stage, and perhaps he was, but he was also a damn good film actor, and that’s all we have left. Let’s appreciate his films while we can.