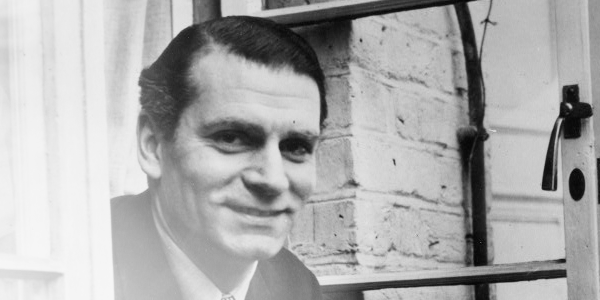

Exciting news: A new Laurence Olivier biography is currently being penned by acclaimed British historian and biographer Philip Ziegler. Philip was kind enough to do an exclusive interview for vivandlarry.com about his work-in-progress. Many thanks, Philip, and I’m sure I can speak for everyone here when I say we’re definitely looking forward to hearing more about it as the project progresses!

Philip Ziegler was born in December 1929 and was educated at Eton and New College, Oxford where he got First Class Honours in Jurisprudence and won the Chancellor’s Essay Prize. After national service in the Royal Artillery he joined the Foreign Service and served in Vientiane, Paris, Pretoria and Bogota. By this time he had written biographies of the Duchess of Dino and the British Prime Minister, Henry Addington. In 1967 he resigned from the Foreign Service to join the publishers, William Collins. After becoming editor-in-chief in 1979 he retired to become a full-time writer. His biographies include King William IV, Lord Melbourne, Lady Diana Cooper, Lord Mountbatten, King Edward VIII, Harold Wilson, Rupert Hart-Davis and Osbert Sitwell, Edward Heath, and he is currently at work on a new biography of Laurence Olivier. He has also written a study of the Black Death and a history of Baring’s Bank. From 1979 to 1985 he was Chairman of the London Library and he has also been Chairman of the Society of Authors and of the Public Lending Right Advisory Committee. In 1991 he was appointed a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order and he is also a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and of the Royal Historical Society. He lives in London and is married, with three children and ten grand-children.

VivandLarry.com: What sparked your interest in writing a biography about Laurence Olivier?

Philip Ziegler: I have always been stage-struck and have wanted to write a theatrical biography – at the age of eighty I felt I could at last indulge myself. Olivier was by far the most tempting subject because he was not merely a great (the greatest?) actor but a major director and one of the most important movers-and-shakers on the theatrical scene. He created the Chichester festival and is more than anyone else responsible for the National Theatre we have today.

V&L: His story has been told many times in an authorized biography, countless unauthorized biographies, by his supposed friends, by his own son, and by the man himself. What do you hope to bring to the table?

PZ: There have indeed been innumerable biographies – though only one which enjoyed access to Olivier’s massive archive. I feel, nevertheless, that I have something new to say – not so much in terms of sensational revelations as in approach. I want to concentrate on Olivier’s role in the British theatre; indeed in the theatre of the Western world. I believe his contribution was massively important and that the theatre we enjoy today would be quite different and less rich if he had never existed.

V&L: You have written acclaimed biographies about many notable British people including King William IV, Louis Mountbatten, Edward VIII, and one of Vivien Leigh’s close friends, Diana Cooper. How has your past work prepared you, if at all, for writing about Olivier?

PZ: Every biography is different yet every biography poses the same questions and makes many of the same demands on the biographer. Few people could be more different than Edward Heath and Laurence Olivier, yet the experience I gained in working on Heath, relating the personality to the career, discovering the forces which drove him forwards or held him back, is as valuable in my work on Olivier is it would be in a study of any politician or monarch.

V&L: What are some of the fundamental issues with writing a biography and how do you overcome them?

PZ: Ideally the biographer should know everything about his subject and then discard 99% of his information, keeping only the essential. Of course, one can never hope to discover anything approaching “everything”, but one can find out a great deal. Some of this may be unpleasant reading and may even hurt or offend people who have been helpful in providing information. The biographer should spare such people’s feelings if he possibly can, but if he discovers something which is of real importance about his subject and there is no other way by which he can make the point, then the material must go in. The biographer’s first responsibility is to the truth and to the reader. If he is not prepared in the last resort to hurt and offend people for whom he feels nothing except goodwill, then he should not be writing a biography.

V&L: Will there be any new material that readers can look forward to?

PZ: I have already come across new and important information and expect to find a great deal more. I doubt whether there will be much which is sensational or scandalous, but I promise that my book will be widely different to any that has gone before.

V&L: What is the most interesting or surprising thing you’ve come across in your research of Olivier thus far?

PZ: I don’t want to go into details on the basis of what is inevitably half-baked and unprocessed material but I can say that I have been surprised by fresh evidence about Olivier’s attitude towards certain of his fellow actors and his views about some of his most celebrated roles.

V&L: How instrumental has the internet been for your research?

PZ: The vivandlarry website has already proved a treasure-house of material which might otherwise have escaped me. I look forward to following it closely. Otherwise, though, I am sure that I will find the internet useful as a means of checking up on minor points but do not expect it to provide information of significant importance. There is no substitute for grubbing through mounds of paper in the hope of extracting a few nuggets of wisdom.

V&L: What have you found to be the most valuable types or resources?

PZ: So far I have hardly got beyond the innumerable (well, numerable, I’ve read over 200 already) books that bear in some way on Olivier’s career and the formidable Olivier archive in the British Library. Next will come the other manuscript collections that are relevant (Gielgud, Richardson, Lord Chandos’s papers at Churchill College and an alarming number of others) and then, of course, interviews with the many people who worked closely with Olivier or who may have information about him. Various other archives – the National Theatre, Chichester – will also need inspection.

V&L: Have you or will you be conducting interviews with people who knew Olivier personally? How wary are you of remembrances of things that happened so long ago?

PZ: See above. Human memory is terrifyingly fallible and I have learnt over the years not to expect precise dates or records of conversations when interviewing people who knew my subject. But the recollections of more-or-less contemporaries can still be invaluable and I look forward immensely to interviewing the people I have been admiring over the footlights for so many years.

V&L: In my years of compiling information about the Oliviers for this website, I’ve found that not every piece of information can be taken at face value. Because there has been so much printed about Olivier over the last century, how easy or difficult is it to piece together a well-rounded portrait? How do you distinguish what’s true and what isn’t?

PZ: Olivier has been endlessly gossiped about and an enormous amount of nonsense has been written about him and then endlessly repeated. As a professional biographer one learns to look at all such material with suspicion. One can rarely be absolutely sure that a story is accurate: a good rule is that if it is (a) surprising and (b) sounds unlikely, then it should not be put in unless some very strong evidence to support it turns up. Quite enough will be left to make possible a well-rounded and, I hope, convincing portrait.

V&L: You’ve mentioned to me that you had the opportunity to see Olivier perform on stage several times. Can you tell us a bit about those experiences? What was he really like as an actor?

PZ: I suppose I must have seen Olivier on stage nine or ten times, and what stays in the mind is the extraordinary power of his presence. However minor his role, he was impossible to ignore. One problem for me is that I feel certain that I saw, for example, his Oedipus, yet can not find the programme for the performance in my pretty comprehensive collection nor find any evidence in my diary that I did so. Could it be that I read so much and talked to so many people about it that I have convinced myself I actually saw it when in fact I did not? What I said about the fallibility of human memory applies just as much to biographers as to anyone else! But this in itself is a tribute to Olivier’s potency.

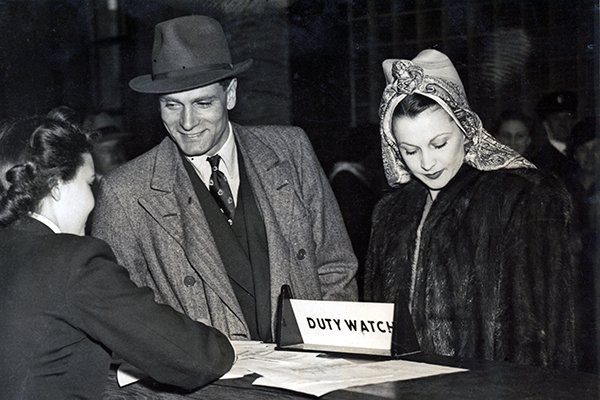

V&L: Did you ever get to see Vivien Leigh on stage?

PZ: I saw Vivien Leigh less often than Olivier but certainly half a dozen times. Her performance in The Skin of Our Teeth sticks particularly in my mind: her charm and radiant beauty. But she was obviously never in the same league as as Olivier when it came to acting.

V&L: How do you think Olivier and Leigh should be remembered by future generations?

PZ: “Future generations” tend not to remember the stars of yesteryear. Only the other day a friend of mine heard a young man wondering why the Gielgud Theatre was so called. But, like Burton and Taylor or, for that matter, Edward VIII and Mrs Simpson, the memory of their relationship will endure for a long time. And his importance in the history of the theatre means that Olivier, like Kean or Garrick, will always remain an important figure to anyone interested in the subject.

*Click here to purchase Philip Ziegler’s books on Amazon

*Special thanks to future biographer Andy Budgell for helping to formulate some of the questions used in this interview.

Great interview, Kendra … you asked exactly the questions I hoped you would. And what praise to know that such an accomplished writer/historian has already been accessing your website on a regular basis to do research! That’s a beautifully timed compliment today on your anniversary. Good for you!

While reading this blog it occurred to me that you and this gentleman have a lot in common, despite the great difference in your ages. To be taking on such an ambitious project at the age of 80 is impressive, and says a lot about his drive and energy and stamina (words that usually make me think of you). I can totally envision you still being at it when you’re 80, buried deep in some old library, “grubbing through mounds of paper”! The idea of that makes me smile. Too bad I won’t be around then to see what you’re up to!

Thanks, David! To let you in on a secret, I had lunch with Philip about a month ago to discuss our respective projects and I showed him the site. I’m really glad it’s proving useful to his research! I need to get the rest of the pages from the old layout back up so it will be more accessible.

I don’t know what I’ll be doing when I’m 80, but digging through archives is one of my favorite things to do at present. I may well still be doing it, but most likely about a different subject as I’m pretty sure by then I’ll have read everything there is to read about the Oliviers. Right now I wish I had the stamina to finish these term papers that are due at the end of the month, lol. 🙂

I’ve been really moved by this interview, this accomplished gentleman in his eighties taking up a new challenge and you so young accomplished on your own, and dedicated with all your tomorrows ahead discussing the life and work of the great Olivier.That’ s part of his heritage and I’m sure Sir Laurence would be delighted

my best wishes for your work! your term papers will be a success, as usual.

I’m glad people are still interested in reading new books about him. It seems like there is always something new to say, and Larry no doubt would have loved that!