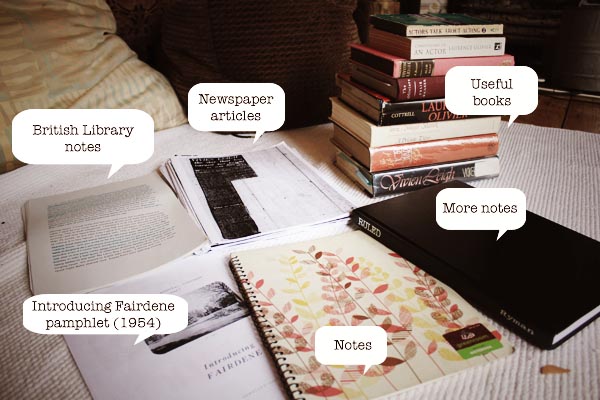

Today, Life.com celebrated the birthday of master celebrity photographer Philippe Halsman. Best known for his “jump” series in which he captured the famous and infamous in mid-air, Latvian-born Halsman began his photography career with French Vogue in the 1930s before enjoying a decades-long partnership with LIFE. During his time with America’s foremost photo new magazine, Halsman shot Vivien Leigh for two covers. He was in awe of Hollywood’s most sought-after actress, but their working relationship proved difficult. Halsman tells his story of photographing an “angel-like star” in his book Sight and Insight (Doubleday, 1972)

++++

No one who has seen her in Gone with the Wind will be surprised that Vivien Leigh became in my eyes one of the most beautiful women in the world. I was delighted when Life asked me to photograph her for a cover.

I knew that she suffered from t.b., but I was shocked by her pale and fragile appearance when she entered my studio. Vivien asked me whether she should put on some rouge, but I saw a strange attractiveness in her transparent paleness and photographed her as she was. Her features were exquisite, she was full of gentile charm and friendliness and at the end of the sitting I had the feeling that I was photographing something very unusual: an angel-like star.

The shock came when I developed my photographs. What I saw was not the image of a fragile, delicate angel but that of a tired and sick young woman. I phoned Vivien and told her it had been a terrible mistake on my part to photograph her without makeup and I hoped she would pose for me again. The angel-like voice answered that she understood and that she would come to pose tomorrow.

We used make-up in the second sitting. Vivien posed with more spirit than in the first sitting, and when her pictures were developed and printed I was delighted with the result.

The telephone rang. It was Vivien, who was worried about her pictures and wanted to see them. Whenever I photograph for a magazine my rule is never to show a picture to the sitter before publication. But how could I say no to an angel, who without complaining left her sick bed to pose for me a second time?

Vivien Leigh captured by Philippe Halsman for LIFE, 1946 and 1951

I finished my work and took the best prints to the Waldorf Astoria where she and her husband, Laurence Olivier, were staying. Although I knew that on doctors’ orders Vivien spent most of the day in bed, I felt a pang of sadness seeing her pale and emaciated in the huge hotel bed. Fortunately, my pictures showed none of her illness, only her beauty and charm. With a touch of pride I was showing her my prints when I was struck by the change in her expression. Instead of and angel I saw a wounded tigress. “These pictures are terrible,” she said, “and I forbid you to show them to the magazine. I know your boss, Mr. Luce, personally; if you disobey me, I will destroy you.”

A knock at the door interrupted her. The hotel waiter appeared with Miss Leigh’s tea and cookies. Where should I put the tray, Miss Leigh?” he asked. With a sweet and melodious voice, Vivien answered, “could you, please, put it on the night table.” The waiter obeyed, looked admiringly at the prostrate angel, deposited the tray and left. When the door closed, Vivien took my beautiful prints and tore them into little pieces. I thought of the hours I had spent in the dark room, mumbled a good-bye and left, feeling completely crushed.

On that same evening, Vivien Leigh’s public relations man called me up. “I know that Vivien has torn up your pictures, but she did not tear up the contacts which you left in the envelope. Olivier has seen them and he is crazy about them. By all means, make new prints and submit them to Life.” I followed his advice, and one photograph, showing Vivien with an alluring Mona Lisa-like smile, became a very successful cover.

Five years later, while in London, I received a cable asking me to make a double portrait of the Oliviers for a Life cover. The sitting room was to take place in the dressing room of a London theatre. I was watching Vivien’s expression when I entered the room. She smiled angel-like and said, “What a great pleasure to see you again!”

Probably because I was still resentful, my plan for the cover was to show only the heads of the couple, with Olivier’s profile covering and eclipsing half of Vivien’s face, since his fame had gradually eclipsed hers.

I placed my sitters in the position I had conceived. However, during the sitting Vivien moved slightly away from her upstaging husband and looked at him with a charming, adoring expression. It destroyed my original design but probably resulted in a much better picture.