Yousuf Karsh seemed destined to become a photographer. Born in 1908, Karsh fled the ravages of war in Armenia and Syria and at age 17 emigrated to Quebec where he lived with his uncle Nakash. Karsh had planned to study medicine, but the gift of a cheap camera from Uncle Nakash set him on an alternative path. Karsh wrote:

While at first I did not realize it, everything connected with the art of photography captivated my interest and energy — it was to be not only my livelihood but my continuing passion. I roamed the fields and woods around Sherbrooke every weekend with a small camera, one of my uncle’s many gifts. I developed the pictures myself and showed them to him for criticism. I am sure they had no merit, but I was learning, and Uncle Nakash was a valuable and patient critic.

An apprenticeship with John H. Garo of Boston was instrumental in Karsh developing his skills as a portrait photographer. Garo encouraged him to hone his photographer’s eye by studying the works of great painters in order to get a sense of (natural) “light, design and composition.” He was also taught the technical aspects of photography, including how to develop his own photographs using different techniques.

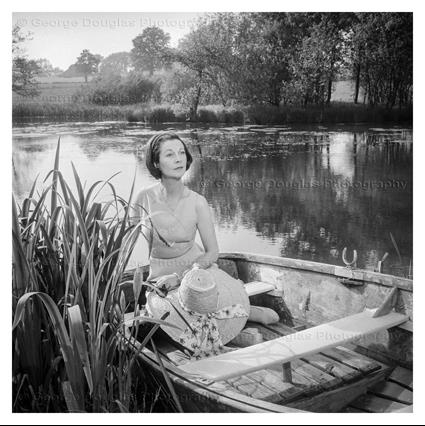

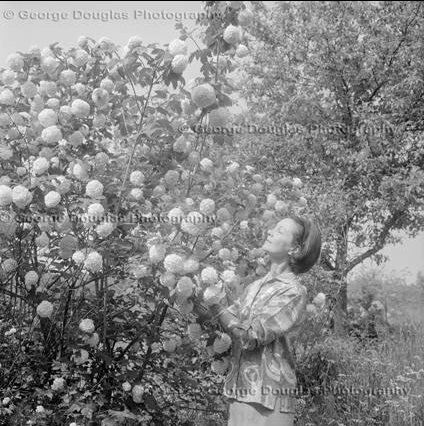

In 1931, Karsh set up a modest independent studio in Ottawa where his work first appeared in print alongside political commentary in an illustrated periodical called Saturday Night. His interest in photographing stage actors developed soon afterward when he was invited to join the Ottawa Little Theatre as a company photographer. It was a prodigious occasion. Not only was he given the opportunity to photograph Lord and Lady Bessborough- whose son was a member of the company – and thereby have his first portraits published in major magazines such as The Tatler and The Sketch, he also met his future wife, the French actress Solange Gauthier.

Further opportunities to photograph luminaries followed in 1942, including sittings with US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. In the years following, Karsh continued to capture leading figures in politics, science and the arts, and in 1958 he published a retrospective of his work titled Portraits of Greatness. It is from this book that the following anecdote about photographing the Oliviers at Durham Cottage in London is reproduced.

“When Sir Laurence Olivier greeted me at his London home in 1954, he appeared fatigued. Small wonder, since he had been directing and himself acting in his film production of Richard III all day long. Besides, he said, he had been wearing a false nose and various other uncomfortable disguises which converted a handsome contemporary Englishman into the hunch-back villain of feudal times.

Sir Laurence, and his petite wife, Vivien Leigh, made a charming couple and did not grudge me their time, even though they were packing for their departure next day to California.*

Soon after the sitting began, their Siamese cat named Boy leapt upon Sir Laurence’s head and completely obscured his face…obviously a privileged character of the household. I snapped a few pictures of this frivolity to remind me, later on, of a great actor mastered by a pet which alone could steal a scene from him.

Presently, while I waited for the right moment for my portrait, Sir Laurence began to talk about the photography used in Hamlet. The magnificent depth of field in this film, the sense of grandeur, of distance and mystery were due, he said, to the use of a special lens and highly imaginative lighting. (He did not mention, of course, the depth, grandeur, and mystery of his direction and acting.) A play like Hamlet, he added, was much better filmed in black and white than in color, for color would undermine the atmosphere of high tragedy.

Several years later, I had the opportunity to meet Sir Laurence again, when he was performing in John Osborne’s play The Entertainer on Broadway. I had wondered why so great an artist had agreed to act a rather sordid part, created by one of England’s ‘angry young men.’ Sir Laurence saw the play in another light. He said he greatly admired Mr. Osborne’s work; in fact, it had been written especially for him, at his own request.

I asked him if he felt that the angry young men were significantly affecting the English drama. ‘Undoubtedly,’ he said. ‘But the term “angry young men” is a feeble press epithet and a misnomer. Some of the critics are greatly distorting the fine work of these playwrights. I think they are definitely contributing something to the stage, in form, in content, and in action.’

When I asked him what difference he found in British and American audiences he gave me a quick reply: ‘I could think of much much more pleasurable ways of finishing my career than answering that one!’ What, I said, did the movies offer to the serious artist? ‘From experience among my friends I would say financially it is fairly all right in both fields and the choice would be entirely one’s own inclination. For myself I enjoy both the theatre and the film media equally but I should say as a general rule that the ilm is the director’s medium and the theatre is the actor’s medium.'”

Unfortunately the shots of Boy the cat on Olivier’s face haven’t been published, but a few prints from his session with he and Vivien have.

*The Oliviers did not go to California in 1956 as intended, much to Vivien’s disappointment. They went to Spain where Olivier was finishing work on Richard III, and then flew to Paris for business.

via the National Portrait Gallery

via the National Portrait Gallery

via the National Portrait Gallery

The Oliviers photographed with Karsh at the London Palladium, 1958

Karsh had these words to offer about the people who appear in his book:

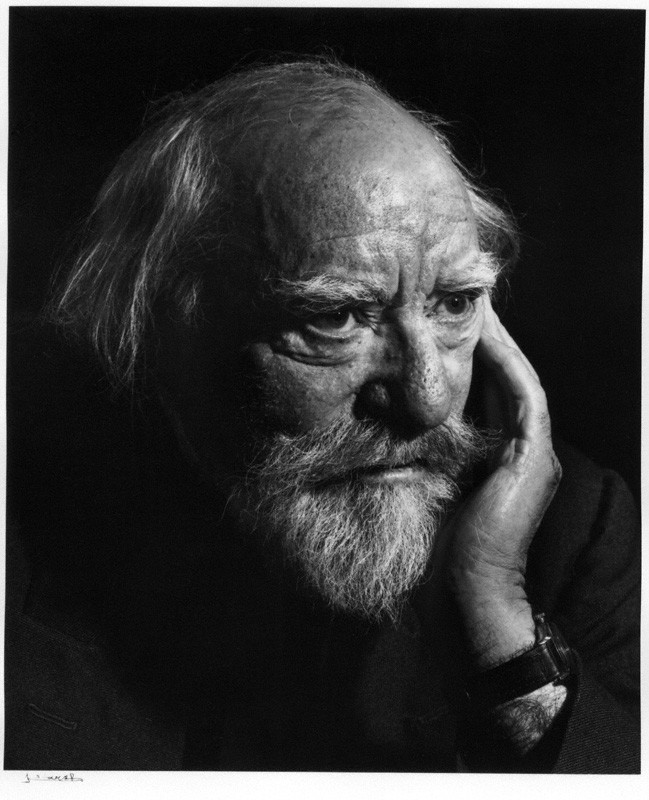

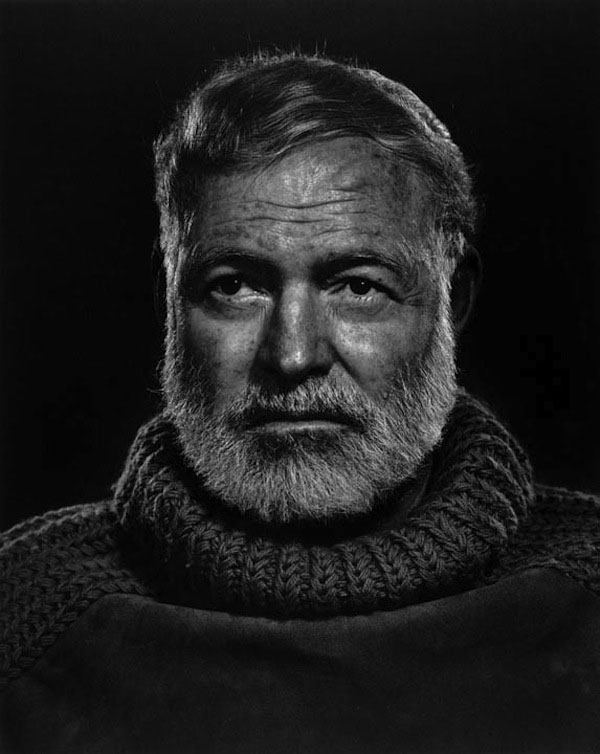

Often, in my experience with distinguished subjects, I have wondered whether the great possess any traits in common. It is my conclusion that they do indeed share certain traits. The physical details of the faces of artists and thinkers vary, of course, but anyone who examines these portraits will observe in them all, I think, an inward power, the power that is essential to any work of the mind or imagination. In all my subjects I indeed expected to find evidence of such power and I was not disappointed. But these faces often bear too the marks of struggle, of the reach that always exceeds the grasp – and sometimes in them is the loneliness of the explorer. They also bear, or so it seems to me, the trace of the fierce competition characteristic of human affairs in our era; sometimes the gleam of arrogance; always the sign of the uncertainty and ceaseless search for truth which, you might say, are the hallmark of the thoughtful man confronted by the dilemma of his species as it is presented today.

Augustus John, Painter. Via the National Portrait Gallery

Ernest Hemingway, American writer.

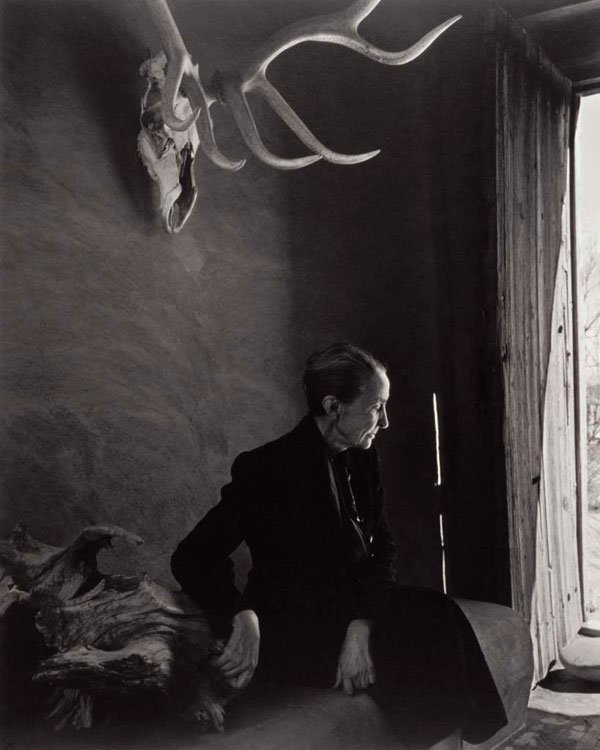

Georgia O’Keeffe, American painter.

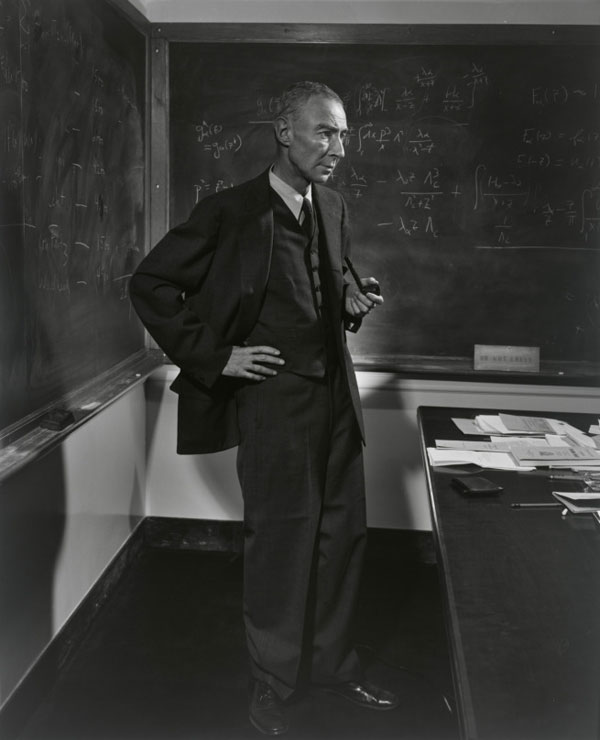

Robert Oppenheimer, American physicist instrumental in the creation of the atomic bomb.

Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.

Former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt

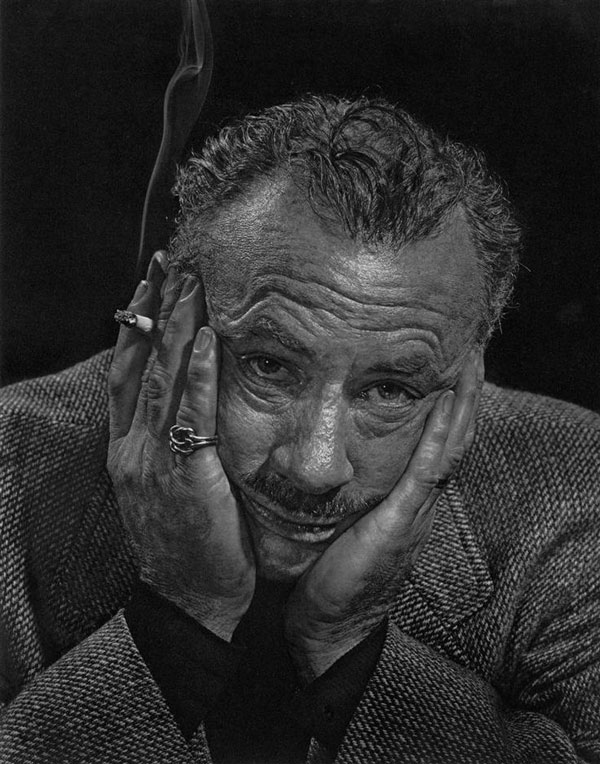

John Steinbeck, American writer.

For more about Yousuf Karsh and his work, visit his page on Artsy.

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠