This is the second of two posts detailing the private view of the V&A’s Vivien Leigh: Public Faces, Private Lives traveling exhibition, which took place last Saturday at Nymans in Sussex. You can read part 1 here.

events photo essay vivien leigh

events photo essay vivien leigh

Seventy degrees and sunny, yesterday was absolutely perfect for a country outing. Robbie and I, along with curator Terence Pepper, took the train down from London to Sussex for the private view of the second leg of Vivien Leigh: Public Faces Private Lives. Formerly a success at Treasurer’s House in York, the traveling exhibition will open to the public on June 1 at the National Trust property, Nymans.

The stately home near Handcross is known for its magnificent gardens and mid-20th century ruins (the result of a fire in 1947). As a newly renovated exhibition space, Nymans is ideal for an intimate show of Vivien Leigh’s size. Its romantic atmosphere is similar to that of the Oliviers’ former country estate, Notley Abbey. You can easily picture Vivien visiting the home and inspecting the gardens. Whether she ever did actually visit Nymans is a question I don’t have an answer to, but there is a connection with Vivien in that Nymans is the family home of the set and costume designer Oliver Messel. Actress and designer collaborated on two projects, once for a Christmas production of A Midsummer Nights’ Dream at the Old Vic in 1937, and again for the 1945 film version of Shaw’s Caesar and Cleopatra – costume pieces from both productions are on display.

Before the festivities, Robbie, Terence and I met up with curator Clare Freestone and her family. I was lucky enough to work with Clare during an stint at the National Portrait Gallery a few years ago. As we had a couple of hours to spare, we wandered the gardens, now in full bloom. Unfortunately, my camera died half way through and I had to switch to using my phone. (Note to self, don’t assume that external battery pack will last forever when it hadn’t been charged in about a year.)

All photos © Kendra Bean, 2016

featured laurence olivier photography

You may not know this, but Laurence Olivier adored Natalie Wood. They worked together in 1976 on a TV version of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, in which she starred as Maggie, with her then-husband Robert Wagner as Brick and Olivier as Big Daddy. In those later years when he was in Hollywood, Larry spent quite a bit of time with Natalie and Robert, who were both in awe of him. Larry and Natalie talked of acting and life and a certain person, undoubtedly. As Wagner wrote in his autobiography, Pieces of My Heart,

Natalie was passionate on the subject of Vivien Leigh, her favorite actress, and the movies she would watch over and over again were Gone With the Wind and, particularly, A Streetcar Named Desire. God, she loved that movie, and she loved all of Tennessee Williams – his particular poetic take on damaged souls.

In her book Natasha: The Biography of Natalie Wood, biographer Suzanne Finstad elaborates on the relationship between Larry and Natalie:

[Natalie] compared acting with Olivier to starring with James Dean, describing them both as “fluid.”

Olivier was “insane about Natalie,” according to their costar Maureen Stapleton. Olivier, ironically, was in awe of Natalie’s beauty, the very thing Vivien Leigh, her idol and his ex-wife, worried overshadowed her reputation as a serious actress.

Larry was often invited on sailing excursions aboard the Wagner’s yacht, the Splendour, where the above photograph was taken. There are so many things I love about this picture: Natalie’s hat, her Espadrilles, her whole boho ensemble, Larry trying to capture her with his Polaroid, what appears to be Catalina in the background, the fact that they’re just sitting there. Together. On a boat. No big deal. The Wagners accompanied Larry to the Century City premiere of the film A Little Romance in 1979, so it is likely the photo was snapped around that time.

guest post london the oliviers

Today’s post comes to us courtesy of Lena Backström, a long-time fan of the Oliviers from Sweden. Over the years I’ve gotten to know Lena fairly well. When this site first launched she kindly contributed scans from her private collection to the Photo Gallery – many of which I had never seen before. It was a real treat. Since then, we’ve met in person a couple of times, catching up over lunch and swapping stories whenever she’s in London for a visit.

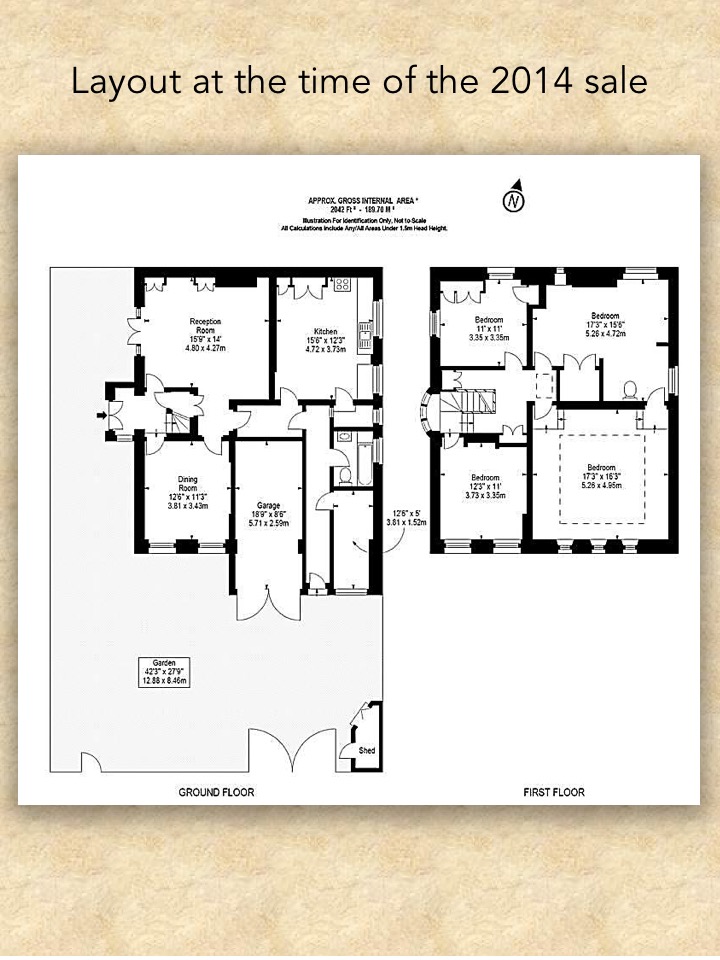

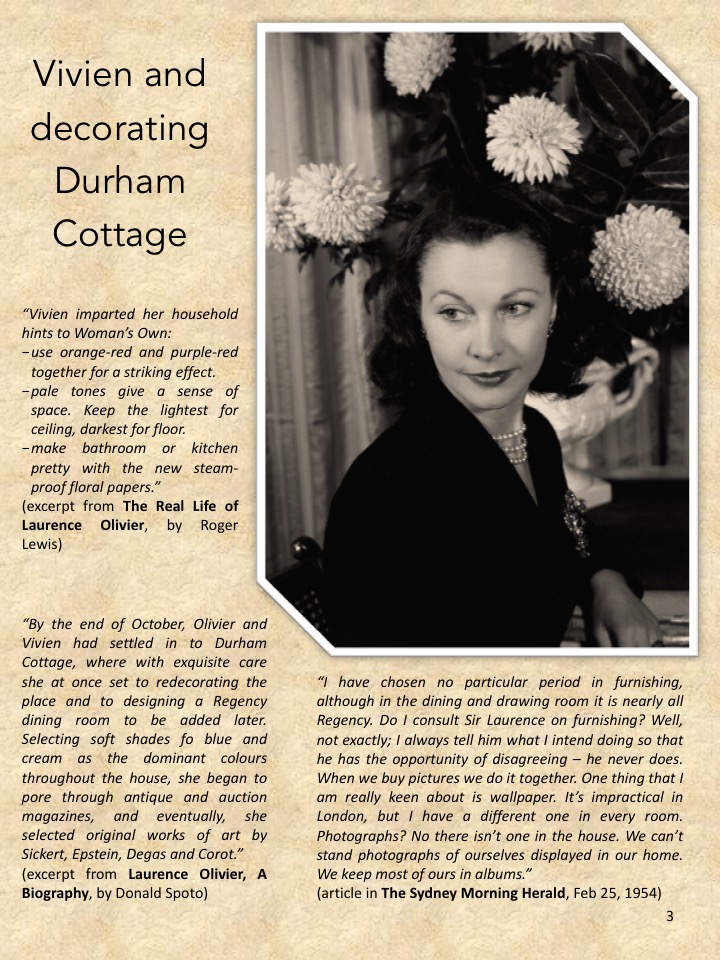

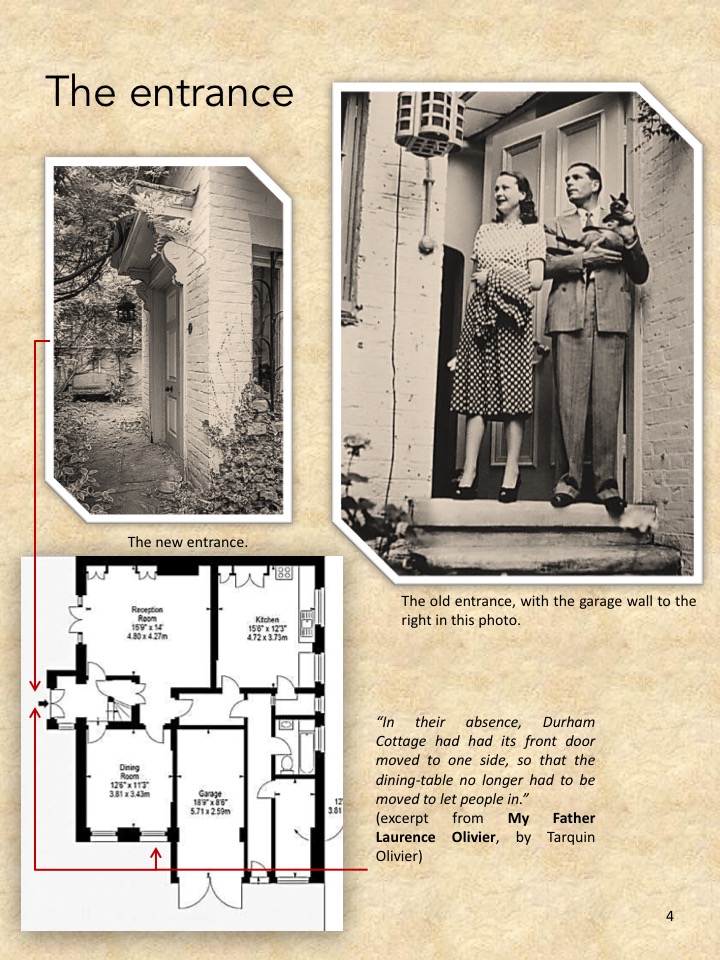

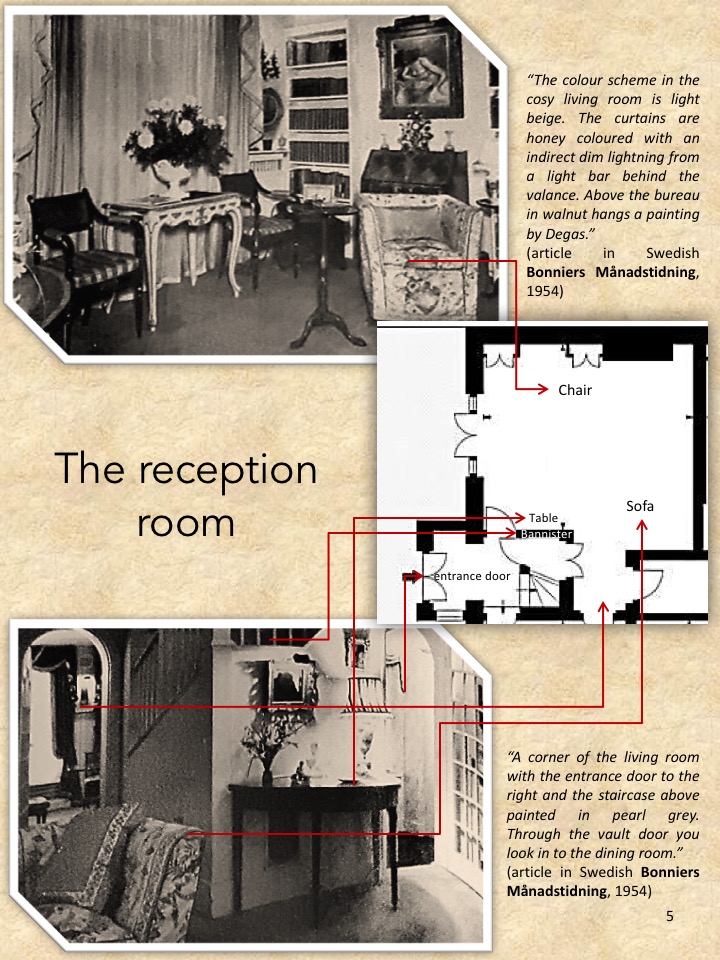

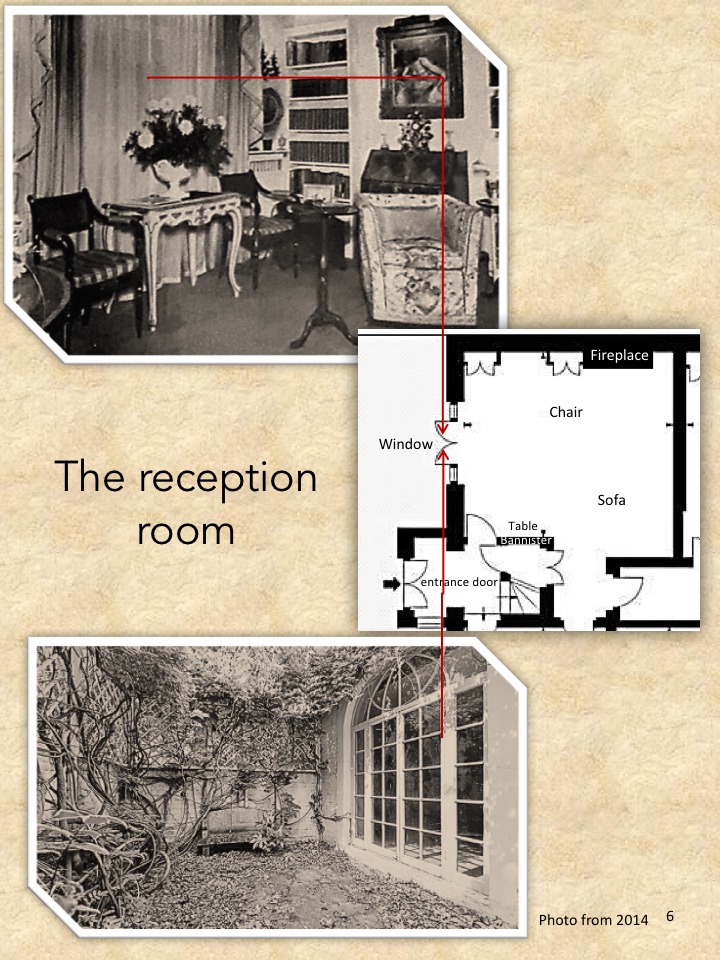

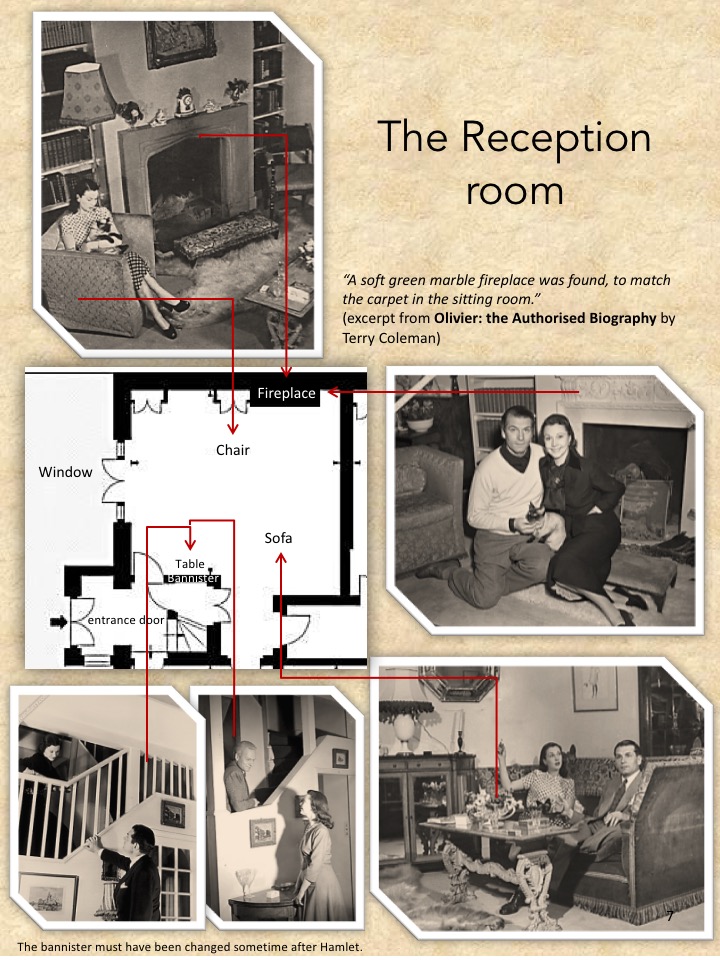

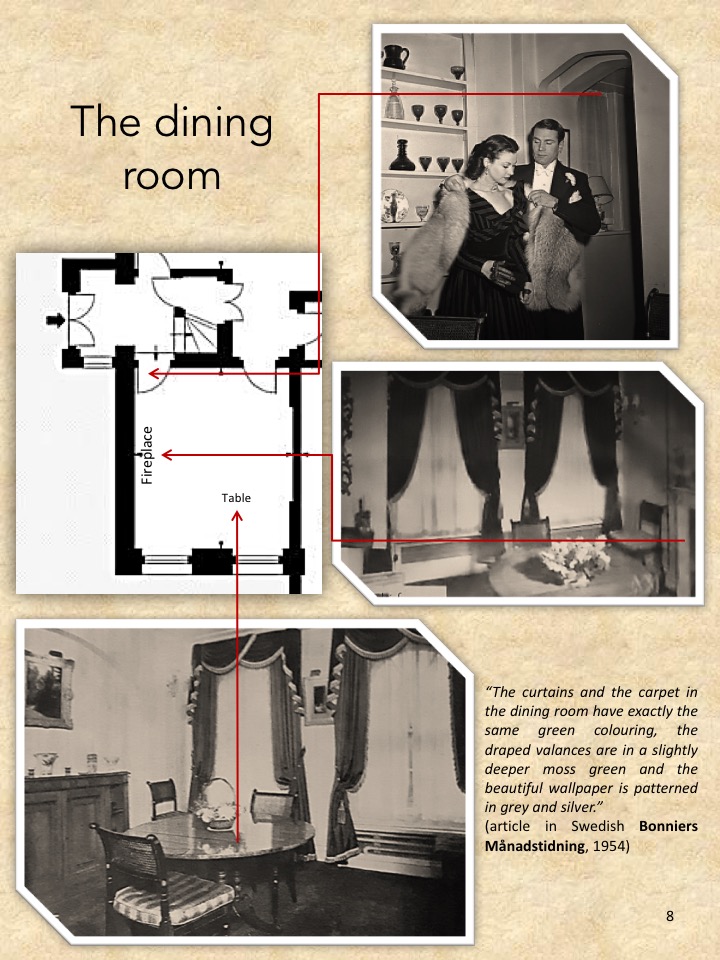

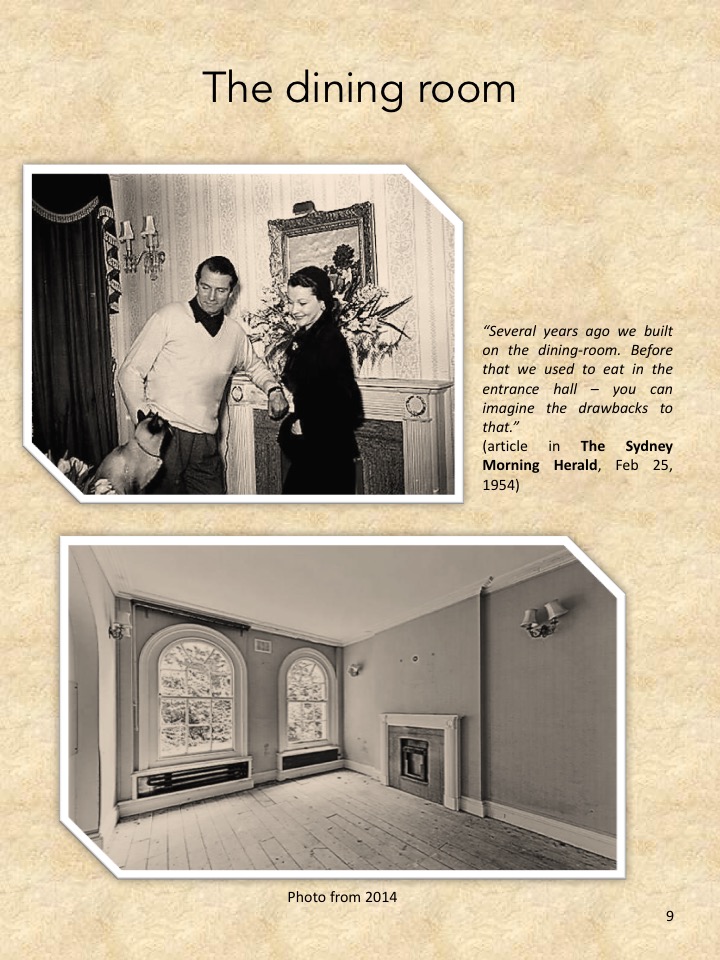

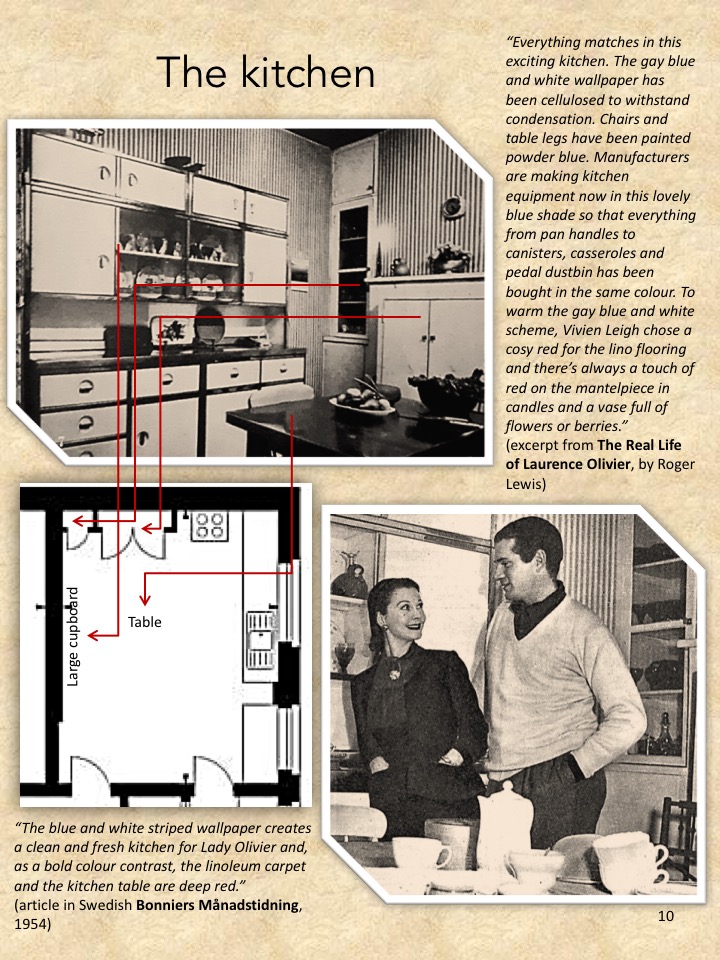

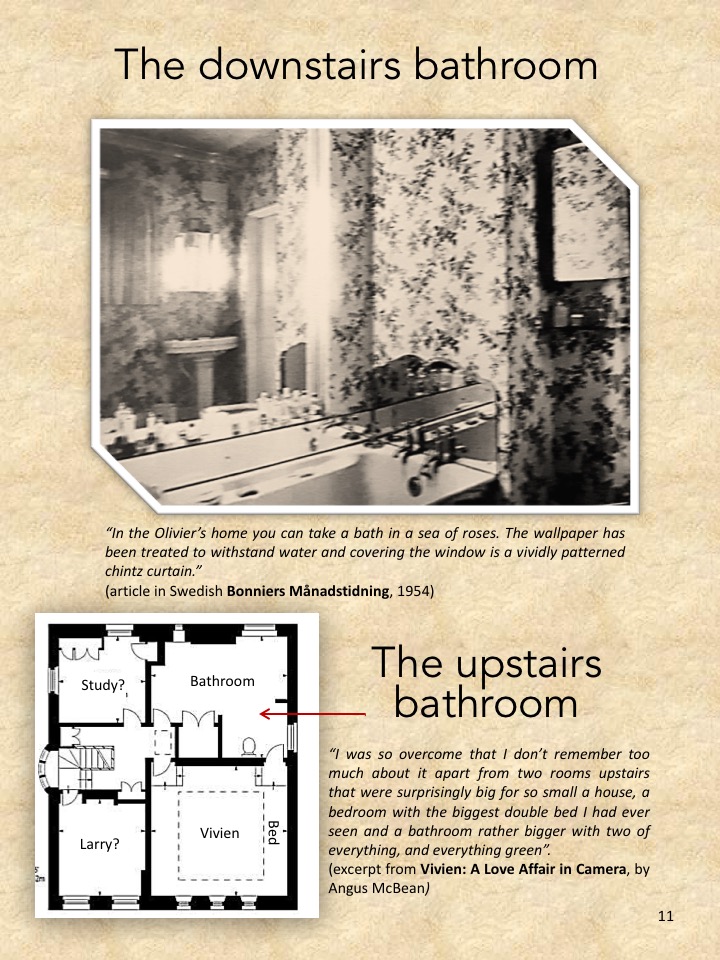

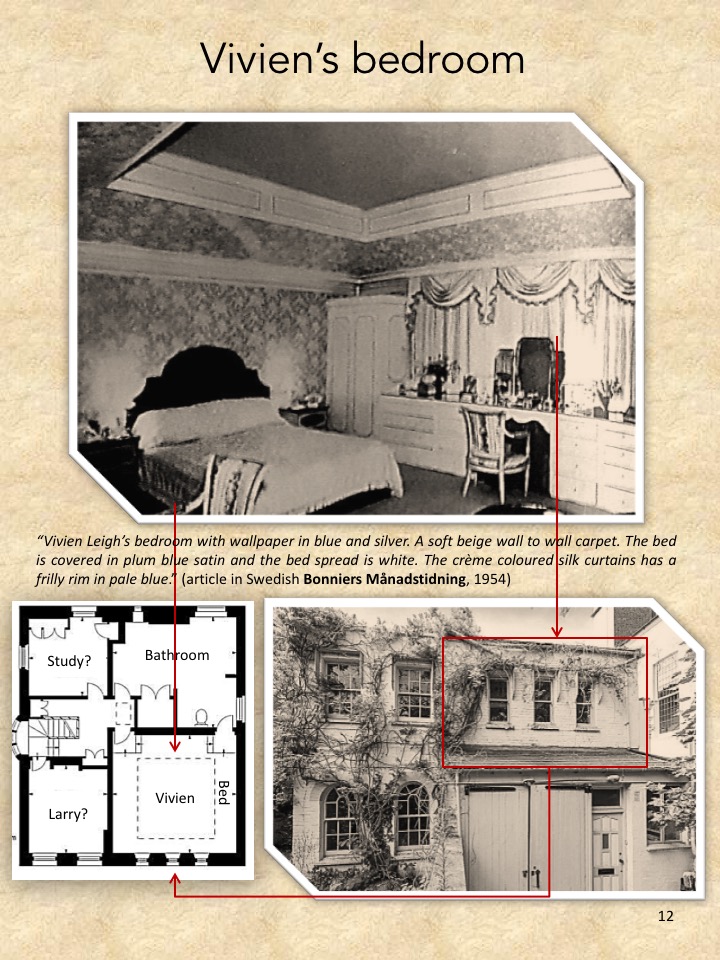

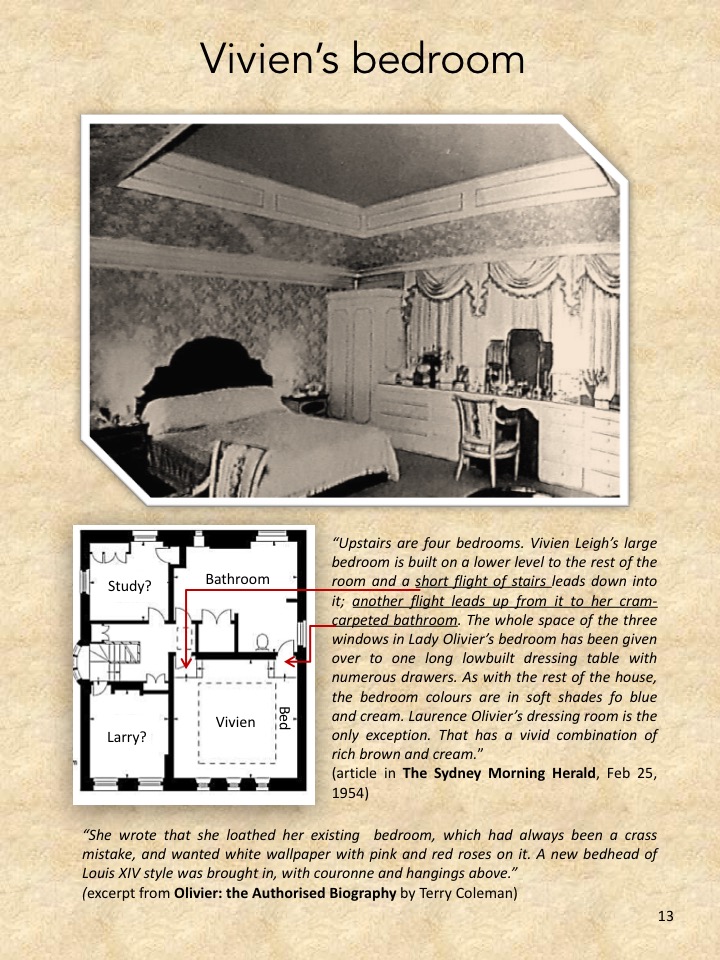

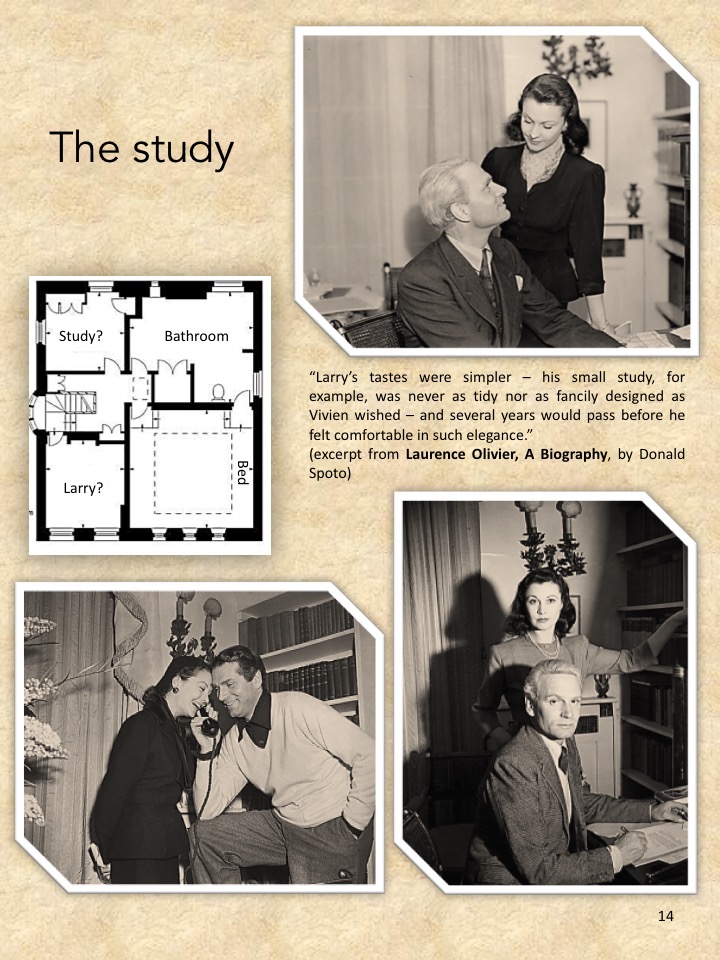

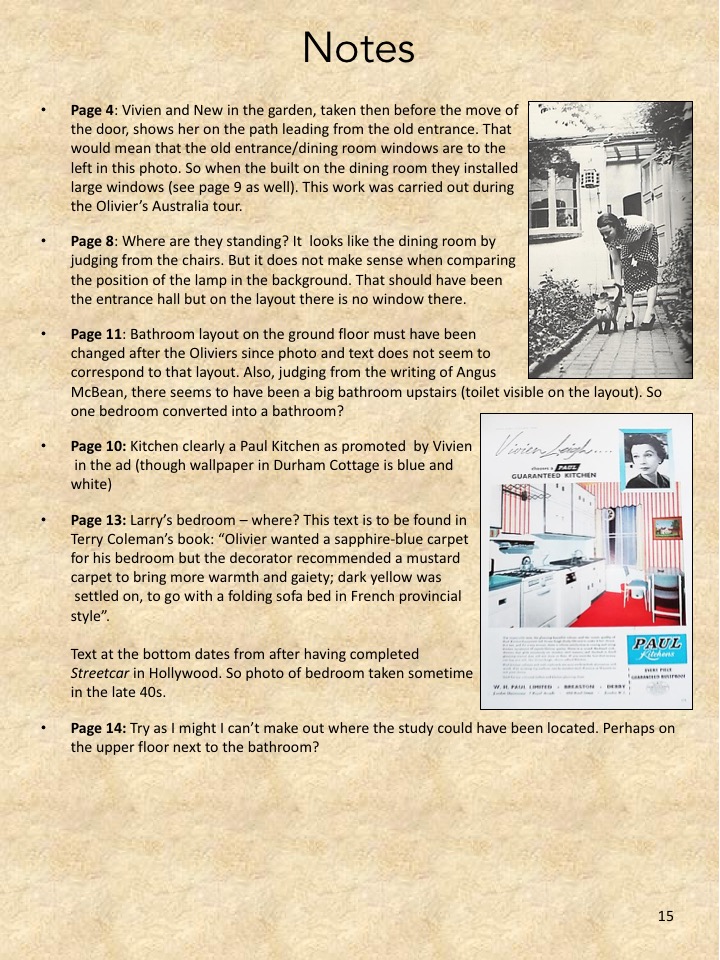

Recently, Lena did some extended research into Durham Cottage, the Oliviers’ love nest in Christchurch Street, Chelsea, west London. Laurence Olivier bought the house (the former coach cottage belonging to the larger Durham House next door) as a London base for he and Vivien Leigh. Using quotes from biographies and excerpts and rare photos from vintage Swedish magazines, Lena was able to plot out what the house looked like when the Oliviers lived there from 1937-1956.

Below is Durham Cottage as we’ve never seen it, but there are some lingering questions: where, exactly, was Laurence Olivier’s study? When did they decide to have separate bedrooms (or were there always two)? Can you help us with the answers?

Thanks for the job well done, Lena!

If you’ve got a unique idea for a guest post and would like to contribute to the content at vivandlarry.com, please get in touch.

I’ve spent a fair bit of time these past few weeks in the V&A and British Library going through fan letters written to Vivien Leigh. It’s research for my chapter in the upcoming V&A/Manchester University Press book Vivien Leigh: Actress and Icon, but I’m also getting pleasure from reading these letters. As a fan who interacts with a lot of other fans on this crazy platform called the Inter Web, I know that we come in all ages, shapes, sizes, nationalities, sexualities, religions, etc. We are all bound together by our mutual interest in Vivien Leigh.

Yet despite my admittance to being a fan, I’ve never written a fan letter to anyone (save for the one I drafted to Leonardo DiCaprio at age 14 and recorded in my middle school diary that I was too nervous to send as my mom probably wouldn’t approve because she thought I was ‘obsessed.’ I was). And I’m not sure, if I had been alive during Vivien’s time, that I would have written one.

The fan letters in Olivier’s and Leigh’s respective archives bring out a range of feelings – wonder at the poetic, eloquent language used by even young people, and the far corners of the globe from which they were sent (India, Japan, Korea, South Africa, Australia); shock at the audacity of some of the writers; happiness at the little gifts of affection sent from around the world and the truly astonishing drawings included in some of the letters. One thing is clear: Vivien was adored by film lovers and theatre-goers far and wide, and they thought her accessible. And while they were just temporary blips on her radar, Vivien meant everything to her fans.

I’m posting the transcribed text from two letters here which have emerged as my favorites thus far. They’re wildly different. The first was penned by a young soldier in the National Service just after the war. The other, by a seven-year-old boy in Australia whose mother, Flora Griffiths, was a frequent correspondent.

What do you think of these letters? I’d love to read your responses below.

November 9, 1946

Dear Miss Leigh, Lady Olivier, what you will,

I am sorry that it has come to this: I despise all fan mails and all fans as a general principle and so I despise myself for writing; tomorrow I shall regret it and say what a fool I have been. What is it that makes me write to night, I do not know: perhaps it’s loneliness, perhaps it is the remains of an adolescent crush, perhaps, and I hope, it’s just a foolish, youthful impulse – for I’ve tons of these and I am, thank God, young.

Then what one should say in a fan mail I don’t know: I could tell you that you are the best actress and the most beautiful thing in this hurly burly world, I could compare you with the sheer beauty of the pale moonlit hills: all these things would be true perhaps – true at least in my mind, but I’ve no doubt Mr. Olivier and others have imaginations too. I’m not jealous, for I have a little sense in my young head. But I would like to tell you one thing and if you haven’t already torn this up, just listen a moment and I’ll let off steam.

Here am I, a conscript in an ugly camp, remote from all the folk and things I love, watching all my principles of art and pure thought get dashed and square bashed to the ground: just now and then I look back home, as every soldier does, and then when the others look back to their respective sweethearts — I don’t. I look to an ideal of culture, of physical beauty and of intellectual [illegible]. I see you very clearly: I don’t want to dash and throw myself at your feet and say ‘Vivien, I love you’ or anything: I just want to see you and know that beauty, real active living beauty is still in the world. And all I want to do now, is tell you that you give me great confidence in the world. You are one of my loveliest memories: One day I’ll marry and love someone, perhaps with dark hair and light expressive eyes, but I promise you now that you’ll still hold a place in my memory box. So thank you.

You’ve probably lost interest so I’ll let off more steam: You realize, I suppose, why Romeo and Juliet failed? Because you thought you could do it without acting to the satisfaction not only of yourselves but of the public. You were wrong and maybe then you decided not to act Shakespeare together again – for I don’t think you have, have you? So by one failure you are disheartened and you are coward enough, the pair of you, to quit a possible production of absolute and complete perfection. Do you not realize that only once in a million years could such a pair as you and Mr. Olivier meet and act? Do you not realize that you have a chance of setting up a romantic masterpiece, the like of which has never been seen? And yet you create only good performances singly, throwing away this chance of perfection. I like to think of you smiling, but only because I know your talent: I like to think of Mr. Olivier as the brave Henry V, but only because I realize he could be other things.

There is a play better than Hamlet; far far better than your Lady Hamilton, and it is time somebody did it properly. It’s called Macbeth: I know it backwards because I’ve studied it (and I mean study) and because I’m a Scotsman and understand. I know I could create a film given the suitable actors and actresses which would be more than a nine days tale. Mr. Olivier has once ruined the part by ranting in the last act but he would know better by now. If I am so confident, surely he could bring the thing about. You could get the experts to give you colorful sets, which would certainly ruin the thing unless they found someone who understood the thing and could control them. But supposing they were careful and were controlled, and deciding you two did decide not to throw away a chance in a hundred centuries, the history of films would be…dated as Before and After Macbeth.

Are you still reading? If so, use your own judgment and choose one of the two courses.

a) leave a passionate adolescent to stew in his own nonsense.

or b) encourage an idealist.

If a) is chosen, stop reading. If b), continue.

When I started this letter I said to myself, I won’t lower myself to asking for a reply: I still don’t. I leave it to you. (But I promise you that this letter was not written for the sake of this final paragraph). You can write me a stereotype letter with photo attached – but for God’s sake don’t autograph it in front, for that would bring you to the same place as Miss Grable’s legs or Miss Lake’s [illegible]. Give me it in the usual way, only untouched and I will keep it as the symbol of the idealist and philosopher of beauty. I will keep it with a picture of the mountains in the rain, that I have, as another side to nature.

But use your motherly judgment, Mrs Olivier. Don’t send it if you think it’s bad for me. I leave the address in the vain hope: some day, some happy day when I see a stage and have the additional fortune of seeing you on it, I’ll come round behind the stage and look sheepish, and say I enjoyed the show, and shift from one foot to the other. No, I don’t think I will.** Anyway, you’re very beautiful as I see you now: as Lady Macbeth you’d look wonderfully villainous though – or can’t I tempt you?

I’ve let off steam, I’ve acted on the impulse: there remains only the question of stamp and address. Then bonsoir, et encore une fois madame, grand merci. Vous étés un joli rêve. Yours with all necessary apologies and with I fear, sincere affection.

1706700 Ptc Kennaway J(ames)

10 pln 2 Coy, 30th training Batt.

Pinefields Camp, Elgin, Morayshire

** It is unknown whether James Kennaway ever saw Vivien perform on stage. The future novelist and screenwriter was 18 when this letter was written. However, it is quite possible that they crossed paths at some point in the 1960s. Kennaway’s first novel, Tunes of Glory, which was partially based on his experience in the armed forces, was made into a film in 1960, starring Alec Guinness and directed by Ronald Neame. Sadly, Kennaway died unexpectedly at age 40 in 1968.

June 17, 1957

Dear Lady Olivier,

I am seven now and I thought I would write to you. Mummy said you live in London where the King lives. Once Prince William and Prince Richard lived in Australia. When I am a man I shall come to London to see you because you are so lovely and Sir Laurence is a beaut sword fighter, he is like a Knight in my King Arthur book. When you come to Australia will you tell me first. Sir Laurence is going to tell the Melbourne boys. The sea is very rough and it is rainy tonight so we have to stay inside. I hope you like your pineapple. I love it. We do not seem to send anything to Sir Laurence perhaps Mummy does not know what he likes, my Dad sometimes likes beer.

I will write again soon,

Love from

Philip Blackburn Griffiths**

Semaphore, South AustraliaWould you ask Sir Laurence if he had time to write me and tell me how to sword fight.

P.S. Later. We have had snow in the hills the most for 50 years. Mummy said we were not here then. I have never seen snow if we had a car we could have got to Mt. Lofty before it melted. Please if you do not save stamps will you keep this one for me and I will get it when I come to London.

**A photograph of Philip, attached in one of his mother’s letters to Vivien, showed a blonde haired boy in a cowboy costume, looking quite like Ralphie from A Christmas Story.

Speaking of Christmas, I’d like to wish you all a merry one, or a happy whatever you celebrate!