Ruth’s Journey

The Authorized Novel of Mammy from Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind

by Donald McCaig

WARNING: This post contains spoilers

In November of last year, the British Film Institute released Gone With the Wind in cinemas across the United Kingdom. The event was the end cap of a successful season in London commemorating the 100th birthday of the film’s star, Vivien Leigh. It also coincided with the theatrical release of Steve McQueen’s critically acclaimed film 12 Years a Slave. Finally, many said, the film business was ready to tell a story that showed one of America’s most shameful institutions in harsh and uncomfortable detail. Why then, would the BFI re-release a film that whitewashed the treatment of slaves during the antebellum era? Guardian contributor John Patterson, who completely missed the point, asked, “Are they looking to generate coattail ticket receipts from the controversy attending Steve McQueen’s harrowing and violent epic? Do they think some retirement-home demographic of faded southern belles and elderly white racists will emerge, stooped and wrinkled, to reclaim it one last time?”

The comparisons to McQueen’s film reared their heads again during the 2014 Oscars when the Academy awkwardly decided to celebrate the glory days of 1939 by ignoring the film that swept the awards that year – and continues to be the highest grossing film of all time – and instead paying homage to the more family-friendly and non-controversial classic The Wizard of Oz. But here’s the thing: Gone With the Wind won’t go away anytime soon. This doesn’t mean that the book and film (both produced upward of 100 years ago) shouldn’t be open to controversy and discussion, or even outrage and disgust. But none of that will stop people from seeking it out and probably even enjoying it. It’s too entrenched in popular culture.

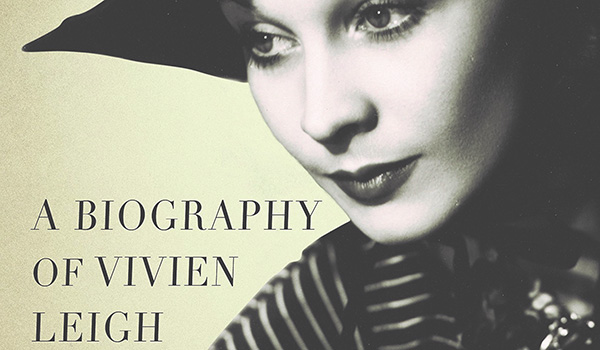

Gone With the Wind is more than a single novel or a single film – it’s an ongoing industry. The Mitchell estate understands that more than anyone, which is why, just a month after 12 Years A Save picked up the Academy Award for Best Picture, Simon & Schuster announced that they would be publishing a new, authorized prequel to Margaret Mitchell’s novel. Ruth’s Journey, authored by Donald McCaig (Rhett Butler’s People, also authorized), would tell the story of Scarlett O’Hara’s faithful Mammy (played by Hattie McDaniel in the film – a performance that made her the first African American Oscar winner). It was strategic timing. The Mitchell estate seemed to be capitalizing on the continued popularity of Gone With the Wind, as well as the controversy surrounding it. In theory, anyway…

On the island of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) at the turn of the 19th century, a slave rebellion threatens French occupation. Solange Escarlette Fornier has left the mother country with her new husband, Augustin, to claim a once-prosperous sugar plantation. “Though Solange was young, she wasn’t beautiful.” (If you haven’t guessed already, Solange is Scarlett O’Hara’s grandmother) She wears the pants in the family and doesn’t care for her husband’s weak countenance (Charles Hamilton, anyone?). While on a scouting mission to capture the runaway, rumored lover of General Rochambeau’s nephew, Captain Augustin’s troop comes across a small shack where they find a slaughtered African family and one lone survivor. The little girl is taken home and presented to Solange who proclaims her beautiful and gives her a name.

Thus begins Ruth’s journey. She follows her new master and mistress to Savannah, stays with Solange through the death of her first husband and marriage to her second, and falls in love with free coloured stair builder Jehu Glen. With Solange’s permission she moves to Charleston, marries and has a daughter, Martine. She finds work as a housemaid at the Ravenel plantation where she is treated kindly. There’s just one problem: Jehu neglects to emancipate Ruth and Martine (because he bought Ruth from Solange, she’s is technically his property and seems strangely okay with that). Unfortunately Jehu dies just before South Carolina makes emancipation a legislative decision, so Ruth and Martine are sent to the auction block. This is not the end of Ruth’s story, of course. She is saved by Master Ravenel and continues to serve as Mammy of the household – until Jack Ravenel becomes a widower and tries to drunkenly take advantage of his indentured servant, at which point Ruth gathers her gumption and tells her Master she’s leaving (he seems strangely okay with that). She returns to Savannah just in time for Solange’s wedding to Pierre Robillard, rejoins the family, and from there goes on to Tara where she serves as Mammy to the three O’Hara girls.

The real challenge any author faces in writing a derivative work of Gone With the Wind is trying to be original within the parameters set down by Margaret Mitchell so that fans recognise it as part of the same canon. Prior to the release of his previous book Rhett Butler’s People, McCaig admitted to not having read Gone With the Wind. It’s clear that he has by now, and he creates backstories of some of the characters mentioned in Mitchell’s novel. For example, we learn that Pierre Robillard is Solange’s third husband and that their daughter Ellen is only the half-sister of Solange’s other children, Pauline and Eulalie. We meet Philippe Robillard, the half-Indian rogue who sweeps his cousin Ellen off her feet, and whose death in a bar fight in New Orleans prompts Ellen to marry Irishman Gerald O’Hara. Real historical characters make appearances (Rochambeau and Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson), as do beloved fictional ones (Rhett Butler, Beatrice Tarleton, Ashley Wilkes, Frank Kennedy).

As I was typing the above potted summary, I thought “Well, that sounds pretty interesting.” Unfortunately, that’s not really what Ruth’s Journey actually conveys. Back in March, McCaig and Atria editor Peter Borland told the New York Times that they wanted to give Mammy a story and a voice. They have, but it’s largely used as a lens through which to project the saga of Scarlett O’Hara’s ancestors. This wouldn’t be cause for complaint except that these other characters emerge as more interesting than Ruth does, and that’s a shame. It’s unrealistic to expect any derivative work to match up to Gone With the Wind. And authors are entitled to their own writing styles. However, one of the things that certainly draws readers in to Gone With the Wind is Margaret Mitchell’s languid, illustrative prose. I remember first reading it as a teenager and feeling like I could step through the pages and be in the story; Rhett Butler, Scarlett O’Hara, and even Mammy seemed so lifelike. Of course, Mitchell did allot 1,000+ pages for her original tome, and Gone With the Wind only spans about 20 years, but she took the time to describe everything from the land surrounding Tara to the elaborate clothes women wore, all of which has allowed readers to fully immerse themselves in the story. In contrast, McCaig attempts to cram nearly 60 years into less than 400 pages. This, combined with his stilted prose, results in flat characters and a plot that hastily skips from one event to the next without giving much weight or depth to any particular incident (when Scarlett’s first period is more memorable than Ruth’s trip to the slaver’s auction house, there might be an issue). Therein lies the central problem of Ruth’s Journey. It doesn’t really focus on Ruth or the experiences of slaves during the antebellum era (or indeed any of the characters therein). And when it does touch on issues like discrimination and cruel treatment at the hands of white people, it’s not written with enough attention or detail to make us feel for these characters. McCaig attempts to make Ruth stand out a bit by revealing that she has second sight – she can predict the future and knows when people aren’t long for this world because she can see their auras (voodoo magic?). But because this isn’t a dynamic characteristic until the end of the book, it ends up seeming gimmicky.

Ruth’s Journey isn’t a terrible book. It’s readable, and it will likely appeal to fans who love anything and everything related to Gone With the Wind. But it doesn’t do much in the way of righting the wrongs in the original story, and sadly, although Mammy may have a voice, she remains largely in the shadows.

I think I’ll re-read Gone With the Wind.

Ruth’s Journey by Donald McCaig is available from Atria Books

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠

You did a good job creating a synopsis that made me want to run and get a copy — and then you pulled the chair out from under just as I was about to settle down. Fine — with this thought. Gone With The Wind, excluding back stories, covers ten years, not twenty. Scarlett is sixteen at the opening and twenty-six at the conclusion. Her age is in response to a specific question from Rhett. Otherwise, good stuff, and I will pass on Donald’s book. (I do not believe that there is anything disgusting in the book or film. The institution of slavery was a fact of life and neither the characters nor the author bear any responsibility for it.)