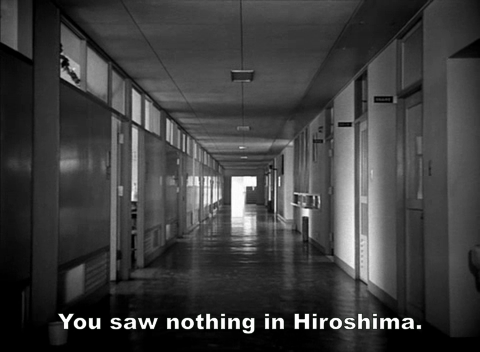

“Listen to me. I know something else. It will begin all over again. Two hundred thousand dead. Eighty thousand wounded. In nine seconds. These figures are official. It will begin all over again. It will be ten thousand degrees on the earth. Ten thousand suns, they will say. The asphalt will burn. Chaos will prevail. A whole city will be raised from the earth and fall back in ashes….”

When I found out Cinema Fanatic and Japan Cinema were collaborating on a blog-a-thon in effort to raise relief money for the recent earthquake and tsunami in Japan, I knew I had to participate.

Admittedly, my expertise in Japanese cinema is lacking, and I can only think of a handful of titles that I’ve seen off the top of my head. You know, the standard Ozu, Kurosawa and Miyazaki films, along with a few other popular imports that could easily be seen in a film class or on the shelf at Blockbuster. So, I decided I would take a different route and re-visit a classic French-Japanese film set in Japan. Hiroshima Mon Amour is French auteur Alain Resnais’ exploration of memory and trauma in the second world war. In a way, it can be seen as a sort of companion piece to his pseudo-art-documentary about the Holocaust, Night and Fog, but more on the artsy side and less focused on documenting one specific event.

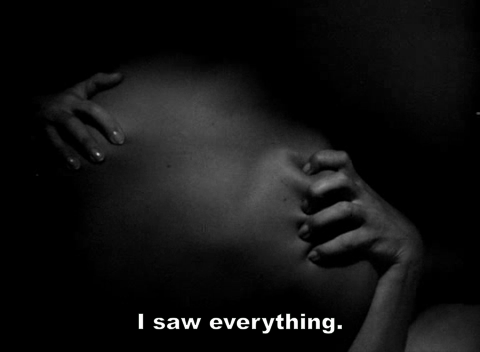

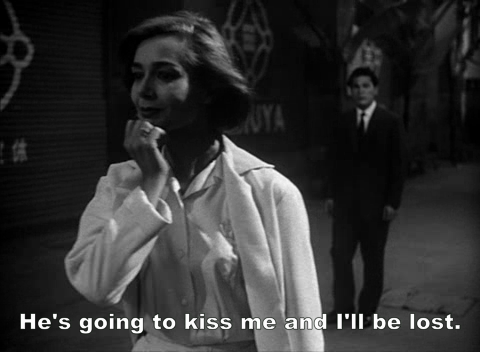

The story is told in a non-linear style and revolves around a 36 hour love affair between a French actress (Emmenuelle Riva) making a film in Hiroshima and a Japanese architect (Eiji Okada) whose family was killed when the atomic bomb was dropped on the city in 1945, effectively ending the war. As the lovers (mostly She) discuss where they were (or where they think they were and are in the present) when the bomb fell and the terrible devastation it brought upon the city, the fictional narrative is inter-cut with brief clips of documentary footage showing mutilated bodies, women’s hair falling out due to radiation, and the physical scars (to say nothing of the mental ones) that the citizens of Hiroshima would carry for the rest of their lives. We later learn that She had suffered similar humiliation and degradation back in her hometown of Nevers, France, when she fell in love with a German soldier. As a punishment, her hair was cut off and she was forced to spend months living in the cellar at her parents’ home after her lover is assassinated and she is discovered with his body. Now in the present, She struggles to find meaning and longevity in her relationships with men, and both try to reconcile the anxieties and traumas of the past.

Kent Jones writes in his essay Hiroshima mon amour: Time Indefinite:

Perhaps it’s not so surprising that Hiroshima mon amour began not as a fiction, but as a documentary. [Anatole] Dauman had successfully pitched the idea of a project about the bomb and its impact to Daiei Studios, and it was to be the first Japanese-French co-production. The title would be Picadon, the “flash” of the A-bomb explosion. It was only after months of reflection that Resnais settled on the idea that Picadon should be a fiction, and that the impact of Hiroshima would be refracted through the viewpoint of a foreign woman. It was Resnais who brought Duras to the project, at the end of the decade when she had achieved literary stardom with Un barrage contre le Pacifique and Moderato Cantabile. It took Duras all of two months to turn out a finished script, all the while working closely with her director. Although Resnais’ links to Eisenstein seem obvious, Griffith’s Intolerance was the film he and Duras had in their heads. “Marguerite Duras and I had this idea of working in two tenses,” he told Parisian journalist Joan Dupont in a recent interview. “The present and the past coexist, but the past shouldn’t be in flashback…. You might even imagine that everything the Emmanuelle Riva character narrated was false; there’s no proof that the story she recites really happened. On a formal level, I found that ambiguity interesting.”

The first time I saw Hiroshima Mon Amour was for a film history class I took as an undergrad. It really is a compulsory title for anyone studying film, and at the time I thought it interesting but pretentious and all but dismissed it. Perhaps this was because I had found Night and Fog incredibly well done and effective, but Hiroshima left me cold. It was not until recently that I learned that Night in Fog was made as more than just a documentary, it was also an artistic experiment. Knowing more about Resnais’ style, I was much more appreciative of the poignancy of Hiroshima this time around.

• • • • • •

Please consider helping the victims of the recent earthquake and tsunami in Japan. Click here to donate.