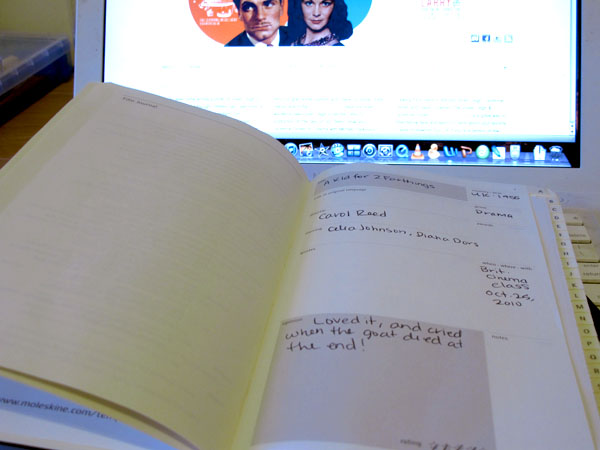

One of my resolutions for 2011 is to keep a film diary. I did well for a good portion of 2010 by posting the films I’d seen on facebook, but stopped after I went back to school. This year, I’m determined to keep up with it. I’ve got my Moleskine Film Journal, which is a great little diary for any film fan (they also have passions journals for recipes, music, literature, wine, and wellness), and I’m going to keep a running list at this blog as well. Hopefully it will spark discussion among fellow film fans as well as provide recommendations! Check out the full list here.

Category: classic film

cinema experiences classic film london vivien leigh

Cinema Experiences: Alfred Hitchcock’s Blackmail

Consider this a new feature here at the vivandlarry.com blog. I’m going to write about my classic-film-going experiences here in London; not films I watch as part of my course, but films I see at the BFI or elsewhere on my own time for fun!

Halloween always brings a handful of classic horror films back onto the big and small screens. This Halloween, I went with my friend Riikka to see Alfred Hitchcock’s last silent film/first sound film Blackmail at the Barbican Centre. The film stars Anny Ondra as a saucepot named Alice who ends up murdering a suitor after he tries to rape her. Her boyfriend, a detective at Scotland Yard, finds one of her gloves at the crime scene–a piece of evidence that would prove her involvement. The couple is then blackmailed by an ex-convict who saw Alice that night. Also appearing in the film are Charles Paton and Sara Allgood (whom fans of Vivien Leigh may remember as Emma Hamilton’s silly mother in That Hamilton Woman).

Blackmail was the last film Hitchcock directed in the 1920s, and was also filmed for sound around the same time, as talkies were just coming into existence. Like many early films of directors who would turn out to be the best in the business, Blackmail was very popular at the box office, but not so much with critics. However, the film uses techniques and motifs that would later become standard in Hitchcock films: staircases, chase scenes, people falling off buildings, etc. It also featured several well known locations in London such as the British Museum and Whitehall (complete with view of Trafalgar Square).

Currently, the British Film Institute (BFI) is raising money to restore all 9 of Hitchcock’s remaining silent films, with Blackmail getting one of the first digital make-overs. The print was gorgeous and crisp. Audience members also got a huge extra treat: the BBC Symphony Orchestra played Neil Brand’s complete new score for the film live on stage while the footage ran behind them. It was extraordinary! Usually silent films are accompanied with a guy and his piano, but this was the real deal. Brand, an expert in scoring silent films was inspired by the music of frequent Hitchcock collaborators Bernard Herrmann and Miklos Rozsa. I think the most mind blowing thing for me was that the orchestra managed to keep exactly on track with the film, without being able to see the images in front of them. The live music really added an extra dimension of excitement to the film and made it seem very of-the-moment.

I wouldn’t be lying if I said this was the best cinema-going experience of my life up until this point. It was absolutely fabulous!

academia classic film general discussion

Fandom and Academia

I had an epihpany today.

I came to London to study for my MA in film because I’m currently interested in British cinema of the 1940s, and of course I got into the whole subject area through my fascination of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier: two of Britain’s most famous film stars. However, I’m always hesitant to incorporate my interest of these two into my written work at school because, well, I’m always afraid professors will take one look at my paper and say “What are you doing? This isn’t ‘academic’ enough. This isn’t what film studies is about. How did you get into this school?” Shouldn’t I be writing about the French New Wave or Italian Neo-Realism and the real “artsy” stuff? Is talking about Vivien Leigh the equivalent of talking about Lord of the Rings or Twilight? I’ve always been afraid that might be the case since film students and scholars seem to keep the notion of fandom on the hush. It’s like, let’s talk about Godard and not mention how much we love Star Wars.

I had a meeting with my British film professor this afternoon to discuss my final paper for the class. I said I was interested in looking at some films (Olivier’s Hamlet and Michael Powell’s The Red Shoes) as related to concept of film as art and “quality” cinema in the 1940s. In talking it through, I realized that it might be a lot to handle for a 15 page paper. My tutor asked whether I was interested in textual analysis of certain films or more interested in a historical approach. I immediately said historical approach. What really fascinates me is the whole notion of how and why these films were made, the political and social constructs of the time, and how they were received. And stardom, let’s not forget stardom.

When I talked to my personal tutor last week, and told her of my purpose for coming here and what I wanted to do with my degree and my life career-wise, she said I totally should incorporate my passion for certain films and stars into my work if I can (well, I was definitely planning to incorporate them into my dissertation, anyway). But I’ve always been a bit sketchy about it. I mean, it’s popular cinema. But when I was discussing my British Cinema paper today, I kept referring to my interest in certain films and the Oliviers in that context, and my course tutor said he didn’t understand why I was acting like my academic work and my obvious passion for the Oliviers had to be two different things. Because they don’t. If I want to write a paper about Vivien Leigh, why shouldn’t I? I said “I don’t know, I always thought it wasn’t academic enough.” And he said it IS academic, and I know a lot about these things, so what I need to do is make sure I focus on specific questions that I can make arguments about in my writing so that it doesn’t end up being a biography, and if I want to use “Larry and Viv” as the means through which to answer these questions, that’s perfectly well and good.

It was so nice to get confirmation about it being okay to write about the things I’m passionate about in an academic setting! HUZZAH! So instead of writing about Hamlet and The Red Shoes, I think I will write about Henry V, Hamlet, and Shakespeare in British film in the 1940s–how J. Arthur Rank marketed these two films, the differences in reception and how they were made. Or something. I’m hoping this Olivier colloquium on Saturday will give me some good ideas. I’m so glad it’s acceptible to be both totally nerdy and smart (har har) at the same time!

I also got to borrow a neat little book called J. Arthur Rank and the British Film Industry! I’m off to go read!

classic film essays friends of the oliviers

Spotlight: Michael Redgrave

I’m mainly writing this post because I’m doing a presentation on Michael Redgrave in the Traditions of British Cinema course tomorrow, and I find that writing things helps me retain information better. The topic we are focusing on in class this week is the Victorian Theatre and Adaptation, and the screening is The Importance of Being Earnest (Anthony Asquith, 1956). But Michael Redgrave and Rachel Kempson were also good friends with the Oliviers, so, huzzah, relevancy for this website! Apologies in advance for this being more like an academic paper than a random blog post.

Michael Redgrave came from a theatrical family (both parents were actors), but acting wasn’t his first ambition. Educated at Cambridge, Michael wanted to be a poet, and after graduating he worked as a teacher before ending up on the stage in the early 1930s. He quickly established himself as a formidable classical actor and counted among his peers Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, and John Gielgud, all of whom would be later regarded as theatrical giants.

British theatre stars of the 1930s were critical of working in film, and considered the stage the foremost place to showcase their talent. In their minds there was a big difference between being an actor and being a film star: acting was solely about the craft whereas being a movie star was more about making money. But it was precisely because the theatre offered such a small salary that many of these actors started doing films in the 30s. Films offered a supplemental income to continue honing their craft on stage.

Michael Redgrave became a matinee idol after playing in Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Lady Vanishes opposite Margaret Lockwood and Dame May Whitty, and unlike some of his fellow theatre actors, he seemed to merge seamlessly into film acting. In the 1940s he had a brief but failed career as a Hollywood screen star, and in the 1950s he started playing character parts on screen with the exception of two major films for director Anthony Asquith: The Browning Version (1951), adapted from Terrence Rattigan’s play, and The Importance of Being Earnest (1956) by Oscar Wilde. Also during this time Michael was lauded as one of the foremost classical stage actors of his generation, and newspapers suggested a “rivalry” between him and Laurence Olivier.

In his article “Postwar Films 2: Adaptation and the Theatre,” Tom Ryall observes that many classical British stage actors in the first half of the 20th Century had difficulty transitioning from stage to screen. They often appeared wooden or “stagey” when they were supposed to be natural. I don’t think Michael Redgrave really had as much of a problem with this transition than someone like Olivier. Michael understood the difference between acting for a physical audience and acting for the camera. He understood that the camera is intimate; that it can frame the actor and show subtle nuances and changes in expression that one would miss sitting in the theatre watching a live performance.

Even though The Importance of Being Earnest was closely adapted from Oscar Wilde’s play and Asquith frames it as a play within a film (as we can see by the opening and closing scenes), there is still a major difference between stage acting and more realistic acting within the film. This film was made during the period when Method acting was becoming really popular in the United States, and actors such as Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift were making waves for digging for emotions within themselves to add realistic depth to their performances. Dame Edith Evans, who had just started acting in films after a long career on the stage, gave a performance in Earnest that is widely called “theatrical,” whereas Michael Redgrave gave a more subtle, quiet, natural performance to try and make it seem more like a film and less like a filmed stage performance (although it should be noted that Michael’s performance in Earnest is still theatrical compared to his performances in The Browning Version or The Lady vanishes). Unfortunately for Michael, Edith Evans’ extremely over-the-top Lady Bracknell is the character that’s most remembered today.

Finally, a major part of Michael Redgrave’s life and work was his homosexuality, and Stephen Bourne suggests that both The Importance of Being Earnest and The Browning Version contain homosexual undertones that probably passed over many critics and viewers in the 1950s. Both Oscar Wilde and Terence Rattigan were gay, as was director Anthony Asquith in times when homosexuality was illegal and punishable by going to prison (as was experienced by Oscar Wilde shortly after the play was published and later Redgrave’s colleague John Gielgud). Theatrical circles were one of the only places that homosexuality was accepted at the time.

It could be argued that the scenes from Earnest and The Browning Version that are most mentioned by scholars can be read as a form of liberation from the oppressive and homophobic societies these artists lived in. According to Bourne, the homosexual undertones in Earnest are closer to the surface than in any other Oscar Wilde Play, and the scene most referenced is the one in which Algernon and Jack/Earnest talk about bunburying. Bunburying meaning inventing another identity with which to pursue pleasures that are unconventional. In The Browning Version, some scholars argue that Taplow’s liking and sympathy for Mr. Crocker-Harris (Redgrave) was actually homosexual in nature.

Whether Earnest and The Browning Version were intended to be read in this way or not, Michael Redgrave’s personal life often affected his stage and screen performances. To the theatre and film-going public, he was a heterosexual leading romantic actor. He was married to Rachel Kempson for over 50 years, but it was widely acknowledged by his wife and his acting peers that he preferred men, however he was never publicly open about it, and it didn’t come out until his son Corin published his book Michael Redgrave My Father after Michael passed away. Still, he often displayed a sensitivity in his roles that was missing from the interpretations of characters that his peers made. His biographer Alan Strachan mentions how Michael usually infused a sense of guilt into his characters and performances that reflected the inner turmoil of his off-screen/stage life. In this way, I think he was more of a method actor than perhaps even he realized.

++++

Of course, Michael appeared opposite Laurence Olivier in several stage plays and films, but he and Rachel Kempson were friends of both Larry and Vivien Leigh in real life. Larry was even godfather to Michael and Rachel’s eldest daughter, Vanessa. The Oliviers were invited to Beford House in Chiswick Mall to watch the Oxford-Cambridge boat race every summer, and the Redgraves often visited Notley Abbey. Rachel was one of Vivien’s closest friends and confidants, especially during Vivien’s affair with Peter Finch. Michael always admired Larry as an actor and though there may have been a few scrapes here and there, I don’t think there was any real rivalry between them. Michael was also set to star opposite Vivien in Edward Albee’s play A Delicate Balance but she died before the first performance.

classic film gone with the wind laurence olivier the oliviers

Now Playing: Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier in September

This month on TCM… Vivien Leigh is being featured as Star of the Month (watch the amazing promo they put together to celebrate her talent and beauty here) and they are also featuring films that deal with the theme of revenge. That being said, there is going to be a plethora of amazing films on TCM in September and I encourage you to tune in! The full schedule is below:

The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone (1962) | September 4, 3:30 am & September 28, 8:00pm … Continue reading

The Roman Spring of Mrs Stone (1962) | September 4, 3:30 am & September 28, 8:00pm … Continue reading