Since her centenary in 2013 Vivien Leigh has been enjoying an extended moment in the spotlight and I am sure I’m not alone when I say it’s pretty great. She has been recognised through exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, V&A, and Topsham Museum. Several one-woman plays have been staged. Actress Natalie Dormer is adapting my own book into a TV series. Vivien’s family made millions from a Sotheby’s sale of belongings from her estate. And Manchester University Press published a compilation of essays examining various facets of her life and career. It’s wonderful that, despite having died half a century ago, interest in Vivien is still going strong.

Category: reviews

My 90 Minutes with Michelle Williams and Kenneth Branagh

Vivien Leigh, marilyn Monroe and Laurence Olivier in London, 1956. The real deal.

Almost everyone who knows me and my taste in films/my appreciation for Laurence Olivier and Vivien Leigh predicted I’d hate My Week with Marilyn, the debut film by director Simon Curtis based on the diaries of Colin Clark. They were right – to a point. The film as a whole is pretty entertaining. I laughed quite a bit (although not always during moments that are supposed to be funny). But I also found myself saying, “what?” and “really?” more often than not. You see, I gave an honest go at having no, or at least low, expectations. I knew it wasn’t going to be a masterpiece of cinema, so it was better than I expected. But from a fan perspective, I wouldn’t call it a “good” film. Not by a long shot.

Clark’s diaries, published as The Prince, The Showgirl and Me (see the documentary made from the book) and My Week with Marilyn were combined to form the basis of the script. Clark (Eddie Redmayne) had family connections to the film industry. His father, Kenneth, was a famous and very wealthy art historian who was the director of the National Gallery and head of the Ministry of Information Films Division during the war. He was also good friends with the Oliviers. When Colin expressed interest in going into filmmaking, Vivien Leigh (Julia Ormond) persuaded Laurence Olivier (Kenneth Branagh) to give him a job on her husband’s next picture, The Prince and The Showgirl, in which he was set to co-star with Hollywood’s it girl Marilyn Monroe (Michelle Williams). Clark details his time working as 3rd assistant director to Olivier. His job consisted of doing whatever anyone told him to do. Somehow he ended up becoming a confidant of the notoriously problematic and troubled Monroe, and My Week with Marilyn covers the week Clark spent in fantasy land with his favorite blonde bombshell.

Michelle Williams and Kenneth Branagh as Marilyn Monroe and Laurence Olivier

Colin Clark had a knack for words and his books make for fun, light reads. This is the sort of reading one might do at the beach, or, in my case, by the pool at my old apartment in southern CA. I quite enjoyed the little insights he gave into the world of my favorite celebrity couple. To be honest, I’ve never cared much for Marilyn Monroe. I recognize her overwhelming star quality, but she’s never moved me as an actress, and the fact that she dominates the pop culture market from beyond the grave (rather like James Dean and Elvis) is off-putting. Therefore, whether Clark’s claims of love on a sunny afternoon near Windsor are true or not is of little interest to me. What his books aren’t are very serious or in-depth. Consequently, the film isn’t very serious either and what we are treated to is a bunch of over the top caricatures of larger-than-life celebrities.

Michelle Williams gives the best turn of the entire film. She doesn’t have the charisma or the curves that the real Marilyn possessed, but she gives an honest attempt at projecting the troubled vulnerability beneath the sex symbol exterior. As the film seems to be a showcase for a possible Oscar nomination, it would make sense that she was allowed to give a deeper exploration of her character. There are times when I did feel sorry for “Marilyn” but everyone around her was so over the top and silly that it was hard to take anyone seriously. Judi Dench phoned in as Sybil Thondike and will probably get an Oscar for her 3 minutes of screen time. Emma Watson is a pointless space-filler as Lucy the wardrobe girl in her first post-Harry Potter role. Dougray Scott was a guy with a cliche and silly New Yorker accent – oh, I’m sorry he was supposed to be Arthur Miller (anyone remember him from Ever After with Drew Barrymore?). Julia Ormond is a lady named Vivien Leigh who thinks she’s no longer loved because she’s 42.

A hot mess

The worst performance was given by Kenneth Branagh. Let me rephrase that, my least favorite performance was given by Kenneth Branagh. All the critics seem to be wetting themselves, saying how he’s a shoe-in for an Oscar and how brilliant he is at capturing the hammy essence of Sir Laurence Olivier. Hammy is right. One could glaze him up and set him on the table for Christmas dinner. I’m sure he’s been waiting to play Olivier on screen his entire life, so now that he’s finally gotten his chance, he went all out with it. In constructing the character, Branagh took some cues from Olivier himself, using facial prosthetics such as a fake chin to give him the famous Olivier cleft (not to mention enough make-up to make him look like a drag queen in training), although he only really looks like Larry in some instances; he simply doesn’t have the fantastic bone structure. He also tries on various voices and dramatic gestures as if to prove he is an actor.

Play acting

The real Laurence Olivier once said of people in his profession, “We ape, we mimic, we mock, we act.” This is exactly what Branagh does. He plays Olivier as a camp, completely over-the-top buffoon, out to steal the show by being loud and obnoxious and trying to get all the laughs. He mimics Olivier but never attempts to get beyond the surface. This is not entirely his fault. There are some instances where he might have had the opportunity to dig a little deeper, such as those involving Vivien Leigh. For example, there is one scene that takes place in a screening room at Pinewood. Larry and Vivien are watching the daily rushes from the film. Seeing the young and beautiful Marilyn flounce around on screen makes Vivien upset and she begins degrading herself (how cliche can this portrayal of Vivien Leigh get, honestly?). Larry, using the nickname he lovingly bestowed on his second wife, takes Vivien in his arms and says, “Oh, Puss, you’re ten times the actress she is.” In a flash, her mood changes (she was crazy, don’tcha know?). “If you could see the way you look at her,” Vivien passionately emotes. “I hope she makes your life hell,” she concludes before storming out of the room. Colin, who witnesses the scene from the doorway, comes in and offers Larry a cigarette, which he takes with slightly shaking hands. In real life, Laurence Olivier’s marriage to Vivien Leigh was on the rocks at this time, and she suffered a miscarriage during the making of the film, adding an extra layer of misery to the stress of dealing with an unprofessional co-star. When he takes the cigarette offered him by Colin in the screening room, we get the tiniest glimpse of what could possibly have been the human side of Laurence Olivier, but the film cuts to the next scene before Branagh can go any deeper. It’s a pity, because in this film Larry comes off as not only cliche but also as a complete tit. What’s so disappointing is that these really are the common perceptions of Laurence Olivier today–that he was camp, a hammy actor and a mean person–and Branagh’s performance, as well as the way this film is scripted and directed, serves only to enhance rather than dispel these views.

For the average viewer who knows nothing about the real people being depicted, My Week with Marilyn probably seems like a good film, or at least some fun, light entertainment. For fans, however – particularly those of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier – it will probably be a disappointment. This film is extremely shallow. The real Monroe, Olivier and Leigh were legends in their own time and they embodied an aura of glamour and mystique that was so essential to classic Hollywood cinema. The actors playing these people completely pale in comparison. For me, My Week with Marilyn just proved that they really don’t make ’em like they used to. If you’re looking for pure, cliche entertainment, this may be the film for you. If you’re hoping for an in-depth glimpse into the secret lives of some of the most famous personalities of the 20th Century, best head elsewhere.

Grade: C

Margaret Mitchell: American Rebel

Margaret Mitchell has been enjoying a second (or 75th?) wind recently due to the fanfare surrounding the anniversary of the publication of her only novel, Gone with the Wind. Atlanta threw a big party and the Windies, a close-knit group of hard-core GWTW fans (think Trekkies in hoop skirts) even made it into the New York Times. As part of the celebration, GPB Media in Georgia produced a new documentary called Margaret Mitchell: American Rebel. It tells the fascinating life story of the woman who would write the most beloved novel in American history.

A progressive, pseudo-feminist yet still very much a woman of her time, Margaret Mitchell was born into Atlanta’s high society in 1900 and was raised on stories told by a generation still sore about losing the Civil War. A tomboy with a creative side, Mitchell always loved writing. At age 16 she penned a novella called Lost Laysen which was discovered and published decades after her death and reveals a sensibility for romance and adventure that would later blossom into a Pulitzer Prize-winner. At 18, Mitchell enrolled at Smith College, the ivy league women’s school in Massachusetts, but dropped out her freshman year (1918) when her mother died of Spanish flu.

Mitchell seemed to take after her mother, a suffragette, and was never content to be complacent within the gender roles society placed on women of her generation. In a time when women were meant to be seen and not heard, Mitchell was more interested in playing sports and hanging around with the boys than she was to be in the kitchen and having babies. When the 1920s rolled in, she made the picture-perfect flapper. She accepted a journalist position at the Atlanta Journal using the pen name Peggy Mitchell and took to the streets, covering important issues of the day and even interviewing Rudolph Valentino.

Mitchell married twice. Her first husband, Berrien ‘Red’ Upshaw, was a violent alcoholic and a bootlegger who commentators on the documentary think may have been the inspiration behind the character Rhett Butler. After the marriage failed, Mitchell wed Upshaw’s best man, John Marsh, whom she remained with for the rest of her life. It was while married to Marsh and convalescing from a broken ankle that Mitchell began work on her magnum opus. She started with the last chapter and wrote sporadically over the course of the next decade.

“If the novel has a theme, it is that of survival. What makes some people able to come through catastrophes and others, apparently just s able, strong and brave, go under? It happens in every upheaval. Some people survive; others don’t. What qualities are in those who fight their way through triumphantly that are lacking in those who go under? I only know that the survivors used to call that quality ‘gumption’. So I wrote about people who had gumption and people who didn’t.”

The fame that came along with the success of Gone with the Wind was overwhelming. Mitchell refused a direct role in helping David O. Selznick with his screen adaptation and became somewhat of a recluse due to the incessant writing and phoning from people wanting to know what happens to Scarlett O’Hara and Rhett Butler after the end of the novel. She never wrote another book and died in 1949 after being hit by a car while crossing Peachtree Street in Atlanta with her husband on their way to see the Powell and Pressburger film A Canterbury Tale. She was 49 years old.

The documentary itself was surprisingly well made and offered commentary from a host of film historians and Margaret Mitchell biographers including Molly Haskell and John Wiley, Jr., co-author of the new book Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind: A Bestseller’s Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood (which I look forward to finally reading once I’m finished with school. I also have a very nice Q&A with the authors to post here, which I also hope to get up soon). The historical re-enactments which are always the bane of TV documentaries were pleasantly unobtrusive. I also learned a lot about Mitchell that I hadn’t known before, such as her role as a secret financial benefactor for the private, historically all-black Morehouse College. This documentary would have been even better if Ken Burns of David McCullough had added their narrative gravitas, but alas. Beggars can’t be choosers, and it was wonderful as is.

If you haven’t yet seen Margaret Mitchell: American Rebel, you can order a copy from GPB. Recommended!

*Screencaps courtesy of Skye Bugs

cinema experiences laurence olivier reviews

Cinema Experiences: Term of Trial

In the 1960s, Laurence Olivier successfully bridged the gap from studio films to the British New Wave with his performance as Archie Rice in the 1960 Tony Richardson film The Entertainer. Two years later he continued his string of “ordinary” characters by playing Graham Weir in Peter Glenville’s Term of Trial, which was screened at the BFI last night as part of their Projecting the Archive series. Jo Botting, the curator of fiction at the BFI archive, gave an introduction before the film. She read excerpts from Sarah Miles’ autobiography and talked about how the film was received upon its initial release.

Term of Trial is one of Olivier’s lesser-known films and, much like in William Wyler’s Carrie (1951), he delivers a quietly powerful and underrated performance as an alcoholic school teacher in gritty northern England who becomes the object of one of his female students’ affection. Graham Weir, despite being a genuinely nice man who wants to change students’ lives for the better through his teaching, is accused of sexual assault when he rejects the advances of young Shirley Taylor (played brilliantly by an 18 year old Sarah Miles in her first film role), his prized pupil. Shirley is so enraged and hurt by Mr. Weir’s rejection that she brings false claims against her once revered teacher. Graham is in a lose-lose situation all around. At home, his nagging, selfish wife (Simone Signoret) accuses him of not being man enough to give her the life she thinks she deserves. He is frustrated at school by the defiance of a trouble-making student (Terrence Stamp), and the accusations brought against him cost him the coveted job of head schoolmaster.

It seems that many people found–and still find–Olivier miscast as Weir, but I thought it one of his best performances. Subdued yet sympathetic throughout most of the film, Olivier the great stage actor breaks free when he is given full reign of the scene when Graham stands accused in court. All of his sublimated emotions and frustrations suddenly explode (we get a glimpse of something boiling beneath the surface in a previous scene when his wife’s comments cause him to violently slap her across the face). Paul Dehn, critic for the Daily Herald said of Olivier’s performance in the courtroom scene:

“Olivier’s own long speech from the dock is a piece of inarticulate agonising as unforgettably delivered as the best of his Shakespearean soliliquies.”

I urge anyone who mistakenly accuses Olivier as being nothing but a hack or ham actor to reconsider his performances in this film as well as in Carrie.

Term of Trial has an all-around strong cast. Simone Signoret was, as always, tough as nails. I had the opportunity to see Henri-Georges Clouzot’s Les Diaboliques the previous evening and was blown away by her performance as a school teacher who helps to murder her colleague’s headmaster husband (with whom she was also having an affair). Sarah Miles was surprisingly very good as Shirley and more than held her own opposite her acting idol. Miles also claims to have had an on and off affair with Olivier that started during filming and lasted for several years. I had only seen her previously in David Lean’s Irish epic Ryan’s Daughter and didn’t think much of her at the time; my mistake. Terrence Stamp (also in his first film role) plays the thug character to perfection, the incarnation of so many angry young men of the period.

What I love about Olivier was his ability to develop his acting style through different filmic periods. From matinee studio idol to Shakespearean expert, everyday average Joe to supporting player in later years. It’s always a pleasure to see the range of his film acting. There are people who insist he was best on stage, and perhaps he was, but he was also a damn good film actor, and that’s all we have left. Let’s appreciate his films while we can.

classic film laurence olivier reviews

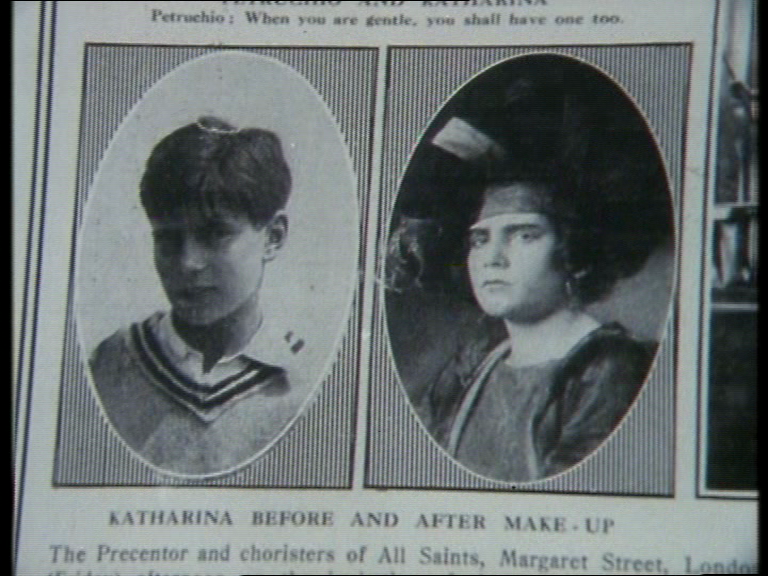

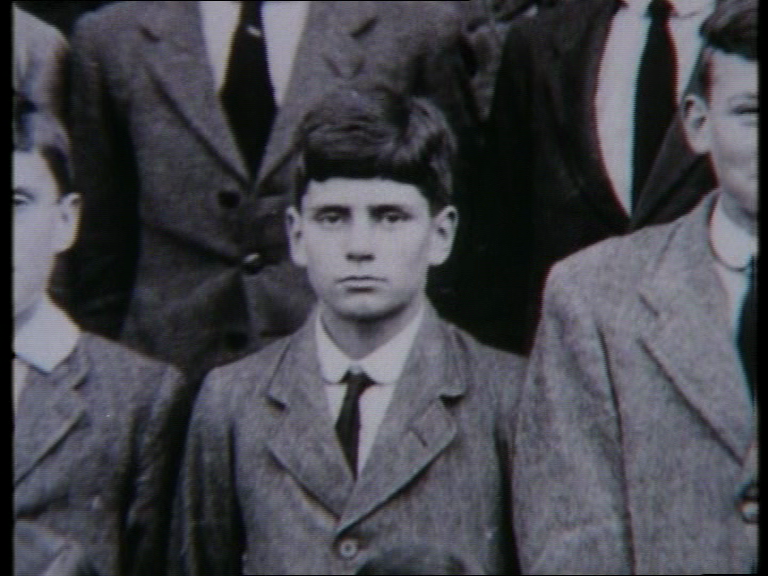

The Curious Life of Laurence Olivier

If you’re looking for a great documentary on England’s greatest actor, look no further than Laurence Olivier: A Life. Well, you can’t look any further because to my knowledge it’s the only documentary made about Laurence Olivier. It also happens to be really good. In the summer of 1982 at the age of 75, to coincide with the publication of Confessions of an Actor, Lord Olivier sat down with reporter Melvyn Bragg over a period of a few days to talk in depth, for the first time, about his life and career.

I had found a VHS copy (2 cassettes) on ebay about 8 years ago and hadn’t watched it in quite some time owing to the fact that I no longer have a VCR, and this doc. isn’t available on DVD. Imagine my happiness when a fellow fan who visits vivandlarry.com sent me a DVD copy all the way from England! Having some spare time last night, I made celery sticks with peanut butter and sat down for some quality time with my favorite old thespian. I was not disappointed.

It’s fascinating to hear Laurence Olivier talk about acting because he was obviously so passionate about it, and confident in his abilities, even if he didn’t always like his work. I do wish he’d talked more in-depth about his personal life, but I have to say I think he gave it quite a good shot in this film. He spoke of how his father terrified and fascinated him at the same time, how he never really got over his mother’s death when he was 12 years old, and how he thought that experience in some way shaped who he had become as a grown man. Larry had a rather rough childhood, but he was determined to make it in acting and he went out and did it, which is very admirable. He didn’t talk much of Jill Esmond, but he did talk a fair amount about Vivien Leigh. He explained how he wanted to marry her before going back to London during the war because they didn’t want to have to deal with leave and special circumstances in a changed environment. He also talks about how he always knew she had what it took to be a great actress, but that it took some years before her talent (on stage) came out and shone as a light on its own. He acknowledged that it was after their divorce that she really hit the mark on her own, and said she was “very remarkable” in the last few years of her life. In the end, Larry turned out to be quite a character.

I thought the way he summed up his life with Vivien was quite interesting and to me, very telling as well, not in what he said, but the way he said it:

“It was a partnership that people felt mighty attracted by…and it involved all sorts of glorious luxuries like Notley Abbey. There were great satisfactions about it, and then various, most unfortunate experiences with illness came upon us–not mine–but things began to become, unfortunately, very very difficult, but I don’t want to talk about that. But on the whole, it was–it was a life. It was a rich experience, but if you’re asking me if I look upon it with a special roseate hue, no. I like my life better now than I have ever liked it.”

Perhaps it is because I’m a hopeless romantic, but every time I hear that clip I can’t help but think he’s lying when he says he doesn’t look back on his marriage to Vivien with a “roseate hue.” It’s his tone of voice, he gets very quiet and sort of far away. I don’t know, maybe he never did, but it’s certainly contrary to people claiming they caught him in his final years watching Vivien films on tv and weeping, saying “This was love. This was the real thing.”

What do you think?

At any rate, I love the intimacy of this documentary, and I love the stories Larry tells. I also love the commentary from a few of his famous friends: a drunken Ralph Richardson, a very eloquent John Gielgud, a very tan Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., and a very classy Sibyl Thorndike. Unfortunately, I don’t think it quite gets tot he bottom of who Larry was as an individual, but I don’t think any biography has every quite gotten there, either. Still, it is a very interesting portrait.

As I said, this documentary is unfortunately not on DVD (even though it should be since it won a bunch of Emmy’s), but perhaps I can make some copies to give away as contest prizes!

Rating: A