All of the posts this week are my contributions to the For the Love of Film: the Film Preservation Blogathon that is being put on by the Self-Styled Siren and Ferdy on Films in effort to raise money for the National Film Preservation Foundation. As film lovers, we should all be aware of how delicate film is and how much of it has been lost due to improper preservation. Luckily for all of us, there are individuals who have made careers out of restoring and archiving movies so that we are able to enjoy them, and so will future generations. To donate to the National Film Preservation Foundation, please click HERE.

——-

Continuing with the Criterion love, today’s film recommendation is very fitting with the theme of www.vivandlarry.com. That Hamilton Woman, Alexander Korda’s propaganda piece involving the real-life adulterous affair of Lord Horatio Nelson and Emma Hamilton, was released in the United States in 1941. It was as much a propaganda picture as an exploitation of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier’s immense popularity and appeal at the time. Watching it for the first time with the commentary track by British historian Ian Christie, I learned quite a bit about the production of the film as well as the fascinating story of the real Nelson and Lady Hamilton.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill supported the film and even sent cables to Korda in Hollywood with suggestions for its title. The main goal of That Hamilton Woman was to make a strong attempt at convincing then neutral America to take up arms with England in the fight against Germany. Christie noted that Hungarian-born Korda was the best person to make such a patriotic British film because he was one of the only people who wanted to revolutionize the British film industry at the time. Korda wanted his production company, the famed London Films, to focus on topics that were essentially British, filming adaptations of British authors and looking at British history–something British producers hadn’t really done up until this point.

Because the crux of the story is the adulterous affair between Nelson and Emma Hamilton, and because it was filmed in Hollywood, Korda had Joseph Breen and the Production Code to contend with. Vivien Leigh’s Emma is a perfect example of how a sinful woman is made to pay the consequences for her lifestyle choices under Breen’s code. This was executed brilliantly by the film’s cinematographer, Rudolph Maté, who played heavily with lighting and the use of shadows to convey mood. There is a great scene toward the end of the film where after dinner in London with the Hamiltons and Nelsons, Lady Nelson (Gladys Cooper) and Emma are talking with one another and we see Lady Nelson bathed in light in the background while Emma, in the foreground, is a silhouette in shadows. We know Emma is the home-wrecker despite being the film’s heroine. The idea that being a bad girl will lead to disastrous consequences is apparent from the very beginning of the film when we see Emma as she was after Horatio’s death, poor and old, stealing wine from a shop in France and being violently arrested and thrown in prison (which really happened). Another facet of the Nelson/Hamilton love story that was tactfully worked around by Korda was the fact that Emma Hamilton had Horatio Nelson’s love child. In the film we know Emma is pregnant when she faints after Nelson’s speech at the House of Lords, but the child is never shown (although according to production stills from the film, at least one scene with Emma and her daughter Horatia was in fact filmed but left out of the final version).

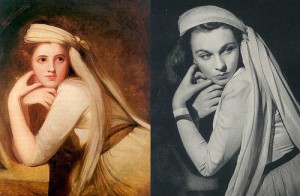

It’s a wonder that this film was able to achieve such a sense of cinematic style, because it was filmed in only six weeks and on a limited budget. The famed art director Vincent Korda (Alex’s brother), can be thanked for making diamonds out of coal. To save money, Alex Korda wanted to have the bulk of the film shot in one interior set. Vincent magnificently designed Sir William Hamilton’s estate in Naples, complete with Mount Vesuvius smoking in the background to give audiences a sense that this was Italy and not a Hollywood back lot (although as Christie explains, Vesuvius couldn’t actually be seen from any such villa in Naples). Vincent Korda also designed the naval battle scenes, which are quite impressive considering this film was made in 1941. Another person who added to the glamor of the film was costume designer Rene Hubert who utilized many paintings of the real Nelson and Emma Hamilton in creating his costumes. Apparently the real Nelson and Emma Hamilton were big fans of making statements with their fashion, and loved dressing up, so this works wonderfully for Leigh and Olivier’s characters in the film.

In 1940/41, Vivien Leigh’s star had eclipsed Olivier’s on screen, due to her popularity after Gone with the Wind. She and Larry had just been married a couple weeks before the start of filming, and after having lost a fortune in their failed production of Romeo and Juliet on stage, accepted the offer to do That Hamilton Woman in large part because it would provide them enough money to go back home to London for the duration of the war. Vivien is clearly the star of the film and is much more natural and luminous on screen than her husband. However, their portrayals give wonderful contrast to one another, and the audience really gets a sense of the fact that despite this torrid love affair, Nelson’s first loyalty is to the British crown, and he is most concerned about saving Europe from the tyrannical Napoleon.

It has been said that That Hamilton Woman was Winston Churchill’s favorite film and that he showed it to everyone, including FDR. It is unclear how much patriotic sentiment his film raised in American audiences upon its release, but my guess is that its greatest appeal was the fact that it starred Hollywood’s dream couple. At any rate, just a month after the film’s theatrical release, the Japanese bombed Pearl harbor and America was thrown into the war.

The London Films library has since been sold to Granada Media, which is where Criterion picked up this film for their collection. I was so glad when I heard Criterion was going to be releasing this movie because my old Sam Goldwyn VHS was not very good quality, and I don’t even own a VCR anymore. The restoration is decent. Although we can still see light scratches in the film, it doesn’t in any way detract from its watchability, and it is suggested that this was part of the original print that was retained when the film was transferred to digital. I have read that there wasn’t much that could be done with Miklós Rózsa’s beautiful score because it was on monotrack.

That Hamilton Woman is a beautiful film on the whole and it is by far the best of the three films that Vivien and Larry did together. If you are interested in Alexander Korda films or the Oliviers in general, I’d highly recommend this film.

Available for purchase on Criterion: yes

Available for streaming on Netflix: no