I have a bunch of magazine and newspaper articles left over from my dissertation research, so I’ve decided to do “31 Days of the Oliviers.” Each day I will post a new article or blog post, ending with Vivien Leigh’s birthday on November 5. These articles (most of which have Vivien as the main subject) span the years 1937-1967 and come from both American and British sources. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I do!

I have a bunch of magazine and newspaper articles left over from my dissertation research, so I’ve decided to do “31 Days of the Oliviers.” Each day I will post a new article or blog post, ending with Vivien Leigh’s birthday on November 5. These articles (most of which have Vivien as the main subject) span the years 1937-1967 and come from both American and British sources. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I do!

****

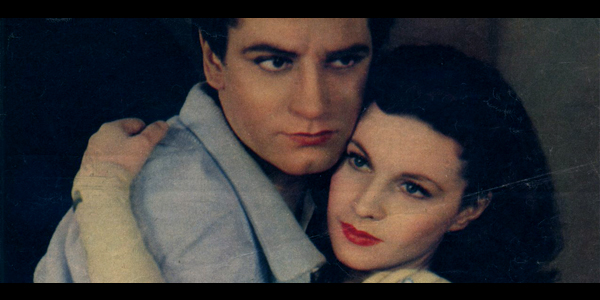

Laurence Olivier’s snobishness toward filmmaking, particularly in the early years of his career, has been well documented. He always regarded theatre as the true actor’s medium but was not singular in his opinion. This was an attitude shared by many British thespians of his generation, including Ralph Richardson, John Gielgud, Michael Redgrave and even Vivien Leigh. Movies were made to boost the bank account and gain wider recognition, but not for developing one’s craft. Therefore it comes as no surprise that Britian’s most popular film fan magazine would attempt to take him, and others of his kind by association, down a peg or two. This is exactly what Picturegoer did in 1937.

An Open Letter to Laurence Olivier

by The Editor

Picturegoer, 1937

Dear Laurence Olivier,

May we be permitted perform the pleasant task of paying a tribute to your performance in Fire Over England before proceeding to the real business on the agenda which may not be so pleasant?

Your success in the new British film, as a matter of fact, lends special point to the issue which we wish to raise here.

Frankly, it is disturbing to find a young actor whom we have some reason to regard as one of the White Hopes of the British screen, going into the old stage artist routine of being superior about “the films”.

“Given a suitable story,” we read in a recent interview, “and no need to sacrifice the stage work he prefers, Laurence Olivier will consent to act in one or two films a year.” The life of a film star, you add does not appeal to you because you wish to develop as an actor, and successes on the screen, except in rare cases like Laughton’s, means doing the same thing over and over again.

“In the theatre,” you point out, “an actor obeys the producer, but he is left alone on the stage.”

Whatever merits this theory may possess, originality is not one of them. It has for years been both the formula of the film failures and the heartcry of every stage actor who has ever considered his art something too delicate to be entrusted to the mechanical medium and too rare to be offered to movie audiences.

One is inclined to be doubtful of its validity now, but if we concede that there may be some justice in some of your complaints, we are still left wondering what a professionally ambitious artiste who can see no chance of development in films is doing in films at all.

We appreciate that your previous experience in pictures has not been an entirely happy one. In Hollywood you had the misfortune to be labelled as “the man who looks like Ronald Colman,” and none of your earlier British films could be called masterpieces.

We recall, incidentally, at Ealing during the production of Perfect Understanding:

The occasion has remained in our memory because our choice of day for a visit was not a particularly felicitous one. Gloria Swanson, who was already beginning to see the danger signals of failure facing her first British production, had just received a cable from America announcing the secure of a valuable collection of furniture over a debt dispute. Michael Farmer (then Mr. Gloria Swanson) was noticeably in the somewhat irritating throes of development into a film star, and Laurence Olivier was at the moment of our arrival the centre of one of those minor storms that blow up even in the best regulated studios.

The point at issue was not, as might be imagined from some of your later pronouncements on the kinema, a delicate question of artistic conscience, but, if we remember rightly, a pair of pants–a pair of short pants–for a Riviera scene, which, we gathered, failed to show off the stalwart Olivier frame adequately.

Perhaps we should be grateful that wardrobe men are also included in your recent enumeration of film hazards for stage actors who take themselves seriously.

Now we do not, for a moment, question the sincerity of your own attitude toward the films, and in any case, you are to be congratulated for speaking your mind so honestly.

Wha we do object to is that the British studios are already full of “spare time” stars. They like the big film money, of course, but they are always in a hurry to get the job over with and collect their pay envelope so that they can dash back to the West End.

And if, owing to the fact that they have given all their energy to their stage performance the night before, their work is not up to form–well, after all, it is only the movies, what does it matter?

One of the reasons why, although money has been poured into the studios, the late lamented bid to capture the world market for British films has failed, is that neither courage nor enthusiasm has been mixed with it.

Hollywood’s enthusiasm is tremendous, even to the point of obsession, but it makes for good films, and in the long run good films make your Laughtons.

The up and coming young artistes one meets there are ambitious to make good in films. They have faith in films as a career, not merely as a stepping stone to personal to personal pyrotechnics, to the applause of hand-picked audiences of sycophants in the repertory theatres and an opportunity for picking up a little easy money.

While we respect your attitude we do not believe you are past praying for. We hope that Fire Over England may enable you to change it.

If, however the worst comes to worst, we can only wish you luck in your choice of “suitable stories” for the vehicles of your future rare appearances on the screen.

You may need it. That artistes are notoriously poor judges of dramatic material should at any rate be known to an actor who once selected the lead in Beau Geste in preference to the lead in Journey’s End.