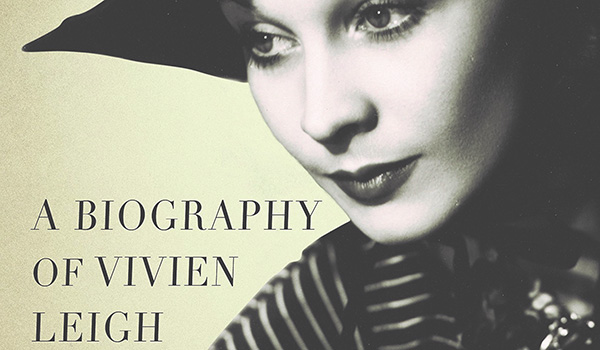

Few 18th century women other than royalty have managed to capture the public imagination quite like Emma Hamilton. Hers is a true rags-to-riches-to-rags story made popular through the media of her time and revived every so often through books about Horatio Nelson and, more recently, serious biographic studies of her own person. There have also been films, the most notable of which was Alexander Korda’s That Hamilton Woman (1941) starring our own Vivien Leigh.

Emy Lyon (also called Emily, Amy, and later Emma Hart before she became Emma Hamilton) was born into poverty in Cheshire on April 26, 1765. Little is known about her life as a child, but we do know that socioeconomic prospects for females of Emma’s station were very slim. In order to improve those prospects, Emma and her mother moved to London in 1778. They settled in Covent Garden, a central hub of art and theatre – but also an area of paupers and prostitutes. Emma found employment as a domestic servant first for physician Richard Budd and then for the household of composer Thomas Linley. It was during her time with the Linleys that Emma likely first developed skills as a performer of the “attitudes” that would make her famous.

One of the Linley daughters was married to playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan who, together with Linley, purchased the Drury Lane Theatre. When Mrs. Linley took up the position of wardrobe mistress at the theatre, Emma became her assistant, mending costumes and dressing actresses, thus gaining a foothold in the storied world of the theatre. Unfortunately, her employment with the Linleys did not stop destitution from nipping at her heels. Emma later admitted to her friend, the painter George Romney, that she did prostitute herself on occasion during that time.

At age sixteen, Emma became the mistress Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh (pronounced Fen-shaw). Being a kept woman to a rich man offered fineries and a sense of security, but it was a precarious existence, as Emma would soon find out. According to curator Quintin Colville, Fetherstonhaugh spent much of his European Grand Tour “in sexual and hunting adventures.” He continues, “Such was the man who betrayed Emma.”

When Emma fell pregnant with Fetherstonhaugh’s child, she was sent back up north to Chester, her money cut off, her security rescinded. Here began the segment of Emma’s life as told in the film That Hamilton Woman. Desperate, Emma wrote to Fetherstonhaugh’s friend, Charles Greville and begged to be taken in. He agreed, on the condition that she gave up her baby. Emma pleaded, to no avail. Faced with the difficult choice of the poor house or financial security, Emma gave her baby daughter to her great grandparents and she was fostered by a family in Manchester.

It was Greville who sent Emma and her mother to Naples to live with his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, British Envoy to the Kingdom of Naples. Believing Greville would soon join them, Emma happily set up shop with Hamilton. But she soon learned that Greville wanted to wash his hands of her, and when she received a letter urging her to “go to bed with” William Hamilton, a spurned Emma responded to Greville: “If I was with you, I would murder you and myself boath [sic].” Emma by then had become resourceful in effort to control her own destiny. She threatened to marry Hamilton, rather than be kept as his mistress, knowing that if the union produced a son, Greville would not receive his inheritance.While in Naples she met Vice-Admiral Horatio Nelson and began a love affair that would propel her into the history books and solidify her as a figure of public fascination.

Now, London’s National Maritime Museum has staged a major exhibition focusing on Emma’s spectacular rise and fall. Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity draws from an impressive array of loaned objects as well as the NMM’s own large collection of Emma ephemera to tell her story in detail and to bring her out from behind Nelson’s far-reaching shadow.

I visited the exhibition a couple months ago and was impressed by the scope of Emma’s story as well as the exhibition design. Disclaimer: when an exhibition leads with an introductory panel featuring a giant image of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier, it’s pretty much guaranteed to capture my interest. This blend of fascinating history and the way the Oliviers were used to represent Emma Hamilton’s portrayal in modern pop culture made me want to know more about Emma and how Vivien Leigh’s screen portrayal compared to the real thing. To find out, I sat down before Christmas for coffee and a conversation with NMM curator Sarah Wood.

KB: Why did you decide to do an exhibition on Emma Hamilton?

SW: It was slightly before my time here, but the research curator, Quintin Colville, was working on the Nelson, Navy, Nation permanent gallery a few years ago and part of that gallery has information about Nelson’s relationship with Emma Hamilton. It’s an interesting story and the scope of what we could do with it in that gallery was quite small. We had a bigger story to tell. At that time, the museum really wanted to do something that celebrated a female life in history. Given the amount of material that we’ve got for Emma here, and the obsession with Nelson, it felt like a good idea.

KB: It’s a great show and I enjoyed it a lot. I love all the objects that you were able to get and I’m wondering, why does the museum collect objects on Emma – is it specifically collecting objects related to her and Nelson or do you collect on her separately as well?

SW: It’s all wrapped up in that section of history and how people know Emma. Historically, the museum has collected on her because of her association with Nelson. Actually, a lot of the things we’ve collected in the past are, sort of, of dubious provenance. They could have belonged to or were possibly associated with Emma. I think her fame was so great and Nelson’s fame was so great that people wanted to attribute something to her. It’s part of the folklore and celebrity surrounding her.

KB: Why do you think people are still so fascinated by her?

SW: I think the context of women in the 18th century and 20th century is obviously extremely different. We have immense freedom in comparison but there are still really interesting parallels that you can draw about fame, about how women are perceived in the media, about celebrity, and about female achievement being still, in some ways, not appreciated in some circles of the media. This is something Emma struggled against – class and gender barriers which, in today’s world of celebrity, may have a different context but on some level may not be that different. She was beautiful as well. And there was something more than her beauty that I think still captures the imagination.

KB: From what I understand, she had some kind of charisma as well. Kind of like what a lot of film stars and theatre stars have.

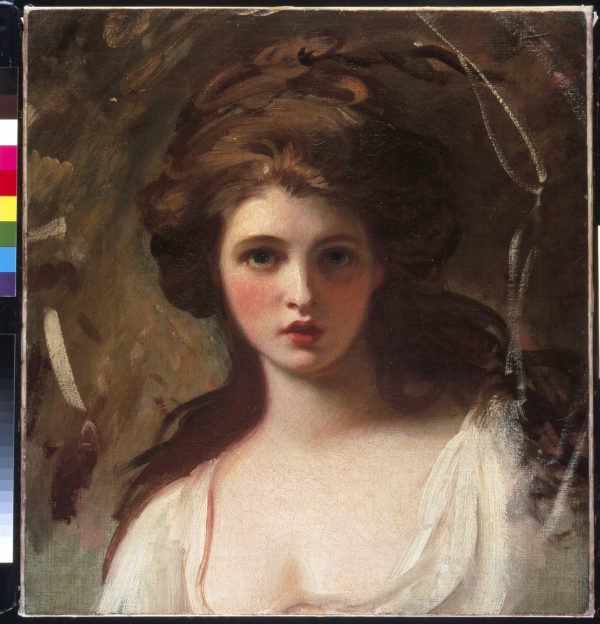

SW: Absolutely. She was beautiful, she was intelligent, she had a drive within her. She started life arriving in London, age twelve, as a servant with nothing and by the age of twenty she was one of the most painted faces, one of the most famous faces in printshop windows, and celebrated by Romney. A few years later she’s an international celebrity because of her own performances of the “attitudes” [poses of historical and mythical women that Emma performed before audiences]. So she was able to negotiate her world that was dominated by men but she obviously managed to go the extra mile. She had an extraordinary trajectory up, and then also down as well. I think that’s the thing that really draws you to the story and to the exhibition. Her life sounds like fiction. You just couldn’t make it up.

KB: She had a nice narrative arc. That’s probably why people like to write about her. I think that’s why I like Vivien Leigh so much. She had a life like that as well. But was Emma really unique in that she became a famous rags-to-riches person at that time, or did that happen to other people too?

SW: In the mid- to late-18th century there are women who achieve. They’re rare cases and it obviously took a certain tenacity. During Emma’s first years in London she works as a servant, but part of the contact of that servant role is that she gets behind the scenes in the Theatre Royal at Drury Lane. So she is, as a young girl, being influenced, we think, by actresses who are making a name for themselves in the world. And being an actress is one of the ways that you could upgrade, claim your own money, and actually have your own career. So there were lots of people like Mary Robinson and Sarah Siddons who were famous in their own right. There were a lot of actresses and that was one way you could achieve, but there were few options for women from poor backgrounds.

KB: It’s extraordinary that she was so seeped in popular culture at the time. What was your favorite part of working on the exhibition? Did you know a lot about her when you started?

SW: No, I didn’t. At the time, I represented a fairly typical person who knows about her, which is that I knew that she was in a relationship with Nelson. I also knew about her through watching a lot of Blackadder; I think there are at least three references to Lady Hamilton, none of which are very flattering and all of which highlight the stereotype of the seductress, the woman who lured Nelson away.

We spent a lot of time at the beginning of the exhibition wondering how we can project this great story to people who don’t know who she is, because once people know even the nutshell of the narrative arc of her life, they’re hooked. It was just getting through that perception. We decided to turn it on its head and actually play to the fact that people know her as being Nelson’s mistress and actually challenge that stereotype and rescue her from the myth. That’s why the exhibition starts with the image of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier as Emma and Nelson – to show people one of the most familiar and more modern representations of them as a couple – and then say, “There’s actually a less film-like story behind this or maybe a filmic and theatrical quality to her whole life.

KB: I think there was. Like you said, it is almost like fiction, but stranger than fiction.

SW: Yeah, and we borrowed that in terms of how we structured the exhibition as well. We deliberately made the visitor’s journey quite long and convoluted so you’re almost following the journey that she makes, including the major geographic transitions from her time in London to her time in Naples and back again when she’s met Nelson and is coming home.

KB: The design is really great, especially that part where you walk through and it’s like you’re sailing across the sea.

SW: The story does have these emotional and geographical places and that’s what we tried to play on.

KB: That was really creative. How did you track down all of the objects that you didn’t have at the museum? There are a lot of paintings from private collections.

SW: Yeah, there are about 240 objects in the exhibition and about 40% are from the National Maritime Museum’s collections here, and there are various connections with institutions in the UK. We borrow from places like the Tate, the National Portrait Gallery, V&A, British Library, so a lot of the paintings are quite well documented. We’ve been working with Alex Kidson, who is a George Romney scholar, to understand more about that relationship because he’s written the definitive Romney catalogue. We’ve also been working quite closely with a private collector in America – the Jean Kislak collection. She is an Emma fanatic and has her own sort of Emma museum of material. It’s a private museum collection but it’s catalogued so we’ve been working with them to bring material over.

KB: How did you find that person?

SW: They did an exhibition of Emma a few years ago using their material. They’ve got a lovely collection – a lot of 19th and 20th century material that shows how she’s been represented since her death, which we chose not to include in this exhibition because we wanted to focus on the whole story. But they have a lot of interesting things, lots of film posters.

KB: Concerning the film, how different is it to Emma’s actual life? I know they sort of played up the whole British propaganda angle for the war and I think they portrayed Emma as a very patriotic person. I think that had a lot to do with Hollywood mores at the time.

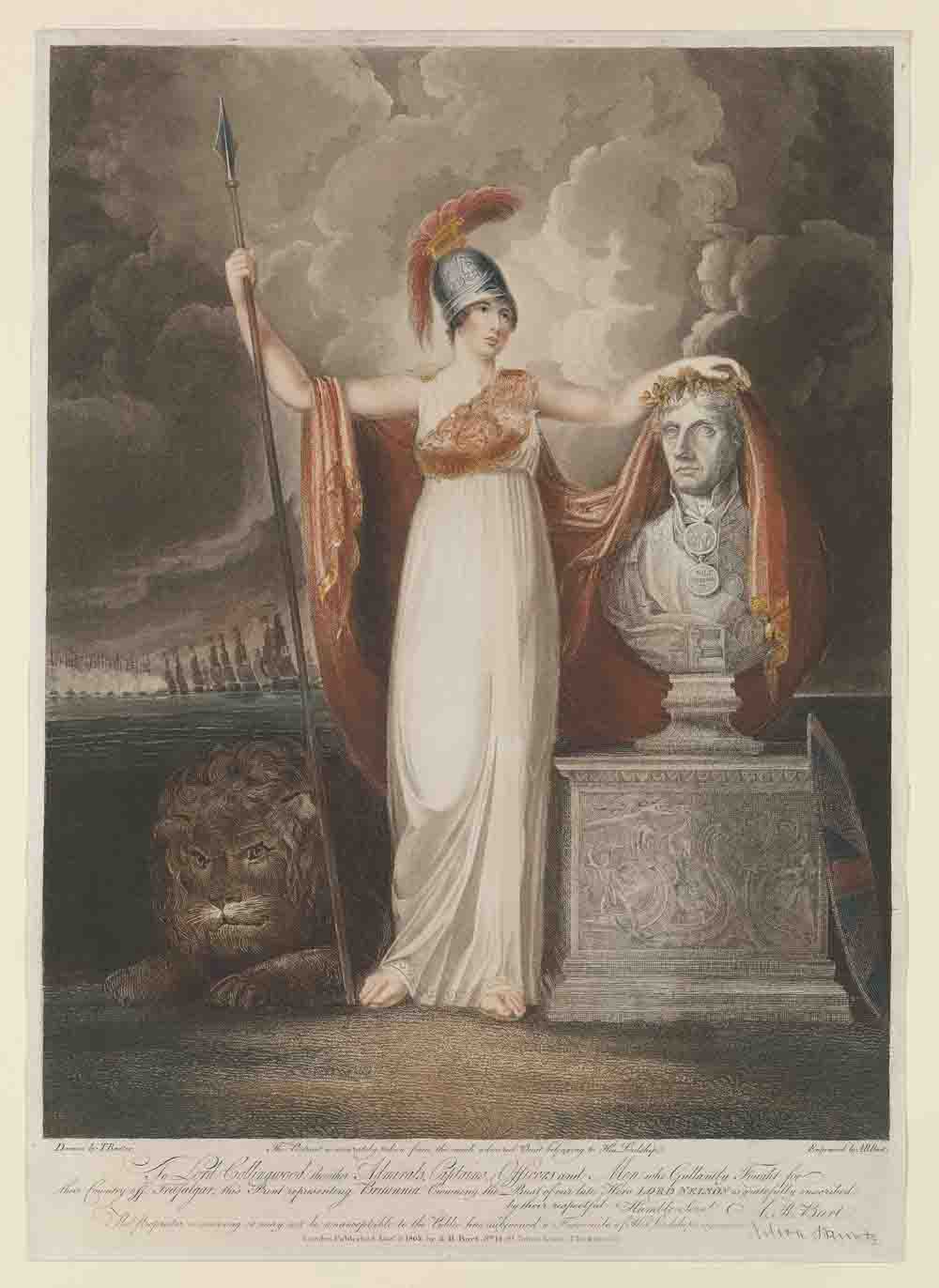

SW: I think she was a patriot and a loyal person both to her friends and the men in her life, and to her country. The time she spends in Naples, after she’s married Hamilton in 1791, she becomes very closely connected with the Queen of Naples – Queen Maria Carolina – and becomes almost like best friends with her and earns her place at court. And because it’s during the French Revolution she is in quite a unique position to be able to negotiate [Maria Carolina was the sister of Marie Antoinette, then Queen of France]. She’s the wife of the Envoy to Naples. By this point she has also met Nelson so she has links to the Royal Navy and is writing to different people. Also, because of the education Hamilton gave her, she’s become fluent in French and Italian, so there are a lot of letters -some of which are included in the exhibition-that show her translating letters on behalf of people from the Admiralty and the Queen. She’s almost like a go-between negotiator, using her skills to be able to do that. Some of the language she uses in those letters is very patriotic. How she refers to Nelson and his victory at the Battle of the Nile – she’s full of admiration for him.

KB: Was she recognized by people back in England as being patriotic, or is she still seen as an interloper with this great hero?

SW: It seems that the only time that Emma is truly accepted as “one of them” in terms of society is really during her performances of the “attitudes.” No one can really accept her in any other walk of life. The marriage to Sir William Hamilton is severely doubted by his close family and friends but also publicly through satirical prints and magazines. There’s a lovely quote from Admiral Keith from the Admiralty toward the end of her time in Naples where it’s acknowledged that she has power because he says, “Lady Hamilton has had control of the Fleet for too long.” In a way it’s a back-handed compliment because they know she has influence, but is it because of their perception that it’s her feminine wiles over Nelson that’s causing this role over any wider skills that she has? But she gets awarded the Cross of Malta from the Czar of Russia – the first woman to ever get that award – for the work she does. She’s involved in rescuing the royal family from French revolutionaries on the mainland and helping them, along with Nelson, to take them to safety in Sicily. So she’s definitely patriotic but there’s a judgmental lens that people view her through because of her relationship with Nelson.

KB: Do you think the film, as a whole, is accurate when it comes to those two characters, or was there a lot of artistic license?

SW: I think when I first watched it quite early on in the research I thought, “Oh, no, this is very silly.” But actually, I’ve watched it a few times since when we’ve gotten more into the subject and although there are some things that are wrong, on the whole, it deals with some of the events quite well. The key of the film is the relationship between Nelson and Emma, so it’s a shame that they largely omit her earlier years, for which there is less documentation but there are over 70 portraits done by Romney. That’s one of the big “wow” moments of the exhibition, those key Romney portraits done between 1782 and 1786, a good ten, 12 years before she’s even met Nelson and she’s famous in her own right. So obviously [the filmmakers] have taken a particular slice which people love to consume, but there are other things that are very exciting. There’s also the interesting thing about the flashback is used in the film. I suppose what we’ve tried not to do is punish. In the film the flashback is her in prison, looking back on her life as this washed up, alcoholic, fallen woman, and yes, she did end her life in prison but we don’t want to punish her as the fallen woman; we want to celebrate her life. The film doesn’t touch on her early years and there’s not much I can remember about the “attitudes”.

KB: No, I think some of the publicity material for the film dealt with that. The photographer for the film, Bob Coburn – he was a freelancer who worked for Sam Goldwyn Studios – he took pictures of Vivien in those “attitudes” for Vogue magazine. So those exist.

SW: Arguably it’s the “attitudes” that cement Emma’s fame and allows the marriage to Sir William Hamilton. Before that she’s been his mistress for five years, but because she is genuinely acclaimed for what she does, she has level of respect among people even if they disapprove of the marriage. It paves the way for it to become allowable, certainly in Hamilton’s eyes. He’s very impressed with her, not just her beauty but her intellect: how she’s picked everything up, how she uses those skills. So he’s more than happy to marry her.

KB: You mentioned earlier that you were thinking of doing a section on how Emma is represented in popular culture today. Were there any specific objects that you were planning to use at the time or did you not really get to that stage?

SW: We hadn’t really developed it to that level. We have a section in the exhibition that looks at legacy but it’s really about how she has been perceived through the lens of Nelson. We did look at how we could bring in different representations of how she was viewed through time because it’s a little bit like what happens to her in her early years where there are shady historical facts about her involvement in the world of prostitution within the world of Covent Garden, none of which are provable, but it’s probable that this was a world in which she had to negotiate. It’s interesting, those 19th and 20th century representations and prints often draw on those early years, they don’t forget that past, even if it’s an imagined past. I think there’s something interesting about those prints of her – lots of naked prints which never actually existed in her lifetime.

KB: So it sort of made her into this character that she may not have been?

SW: Yes. She was loyal to the men around her, with the exception of the transition from Hamilton to Nelson, but within that relationship it was openly accepted by Hamilton that they would live a ménage à trois in certain aspects and dynamics. Before that she was completely loyal to Greville who was Hamilton’s nephew, and before that to Sir Harry Fetherstonhaugh, and it’s actually the men who let her down rather than her being this scandalous adulterer.

KB: Do you know what happened to her first child?

SW: Yes, she gets pregnant at the age of 16 by Harry Fetherstonhaugh, who is an aristocrat that has taken her under his protection as his mistress and she lives with him on the grounds of Uppark, his house in Sussex. But he is not interested in keeping her as a mistress when she has a child, so she has to give it up. She finds Greville, who is Fetherstonhaugh’s friend, and negotiates with him that he will take her under his wing and protect her as his mistress. But he will only take her under certain and specific terms that he lays out to her. Imagine how desperate she would have been at the age of 16, basically about to be left vulnerable with no money, and pregnant. Greville kind of cuts her a deal and says she must live a retired life and do exactly as he says, and she has to give up her child. The baby [also called Emma, who would go by the name Emma Carew], was given to Emma’s grandmother in Cheshire, and Emma does, in the early years, go make visits and writes quite anguished letters about going to see the child. She still hoped that [Greville] might change his mind and allow the child back. Eventually, in her later life, little Emma becomes a governess and [she and her mother] never really connect again.

KB: My final question is: Do you have a favorite object in the exhibition, or are there one or two objects you think people should pay particular attention to?

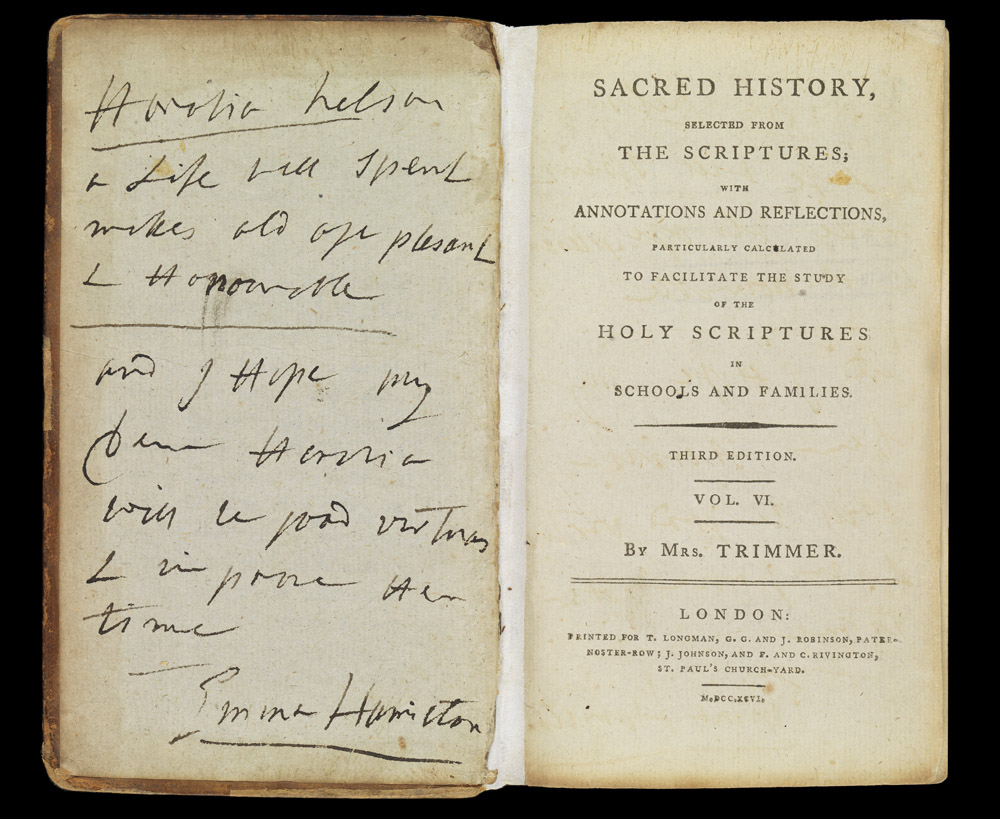

SW: In this exhibition it’s so hard because of how all the objects link together in the story. We’ve got lots of fantastic letters on display. Two letters, maybe, are my favorites. One is not written by Emma but it’s written about her and it’s about class snobbery. It’s a letter written by a man called Heneage Legge to Greville about his uncle Hamilton and the potential threats and rumor that he’s going to marry Emma. We’ve taken an extract that you can listen to – there’s an audio point and the letter in the exhibition – but in a much longer way it talks about how Emma may be good as a mistress and she may be quite good at those “attitudes”, but there’s a general horror in the letter that Hamilton would actually consider marrying someone of Emma’s status and background. He’s completely horrified and he’s writing to Hamilton’s nephew to say, “We must all ban together and stop him making this terrible decision.” So it says something about the class system and about views toward women. It’s such a sneery letter and that’s why we chose it for audio because you can really hear the venom in his voice and the horror of the 18th century class system being illustrated.

The second letter is – we have very very few of Emma’s actual letters. We’ve got a lot of Nelson to Emma but very few of her to him because he, for reasons of discretion, destroyed her letters. But we do have, through another private collector, what we think is the last letter that she wrote to Nelson before he died. It’s on the wall before you go into the fourth section of the exhibition.

In some ways, this is a very normal, everyday letter. Nelson died on October 21st, 1805 in the Battle of Trafalgar, and she’s writing just before then. The letter arrives on the Victory but he doesn’t ever open it because he’s already been mortally wounded. But in that respect she is still full of hope, making plans for the future. And that’s something really nice about their letters; you can glean a lot from the other side of those thoughts. They’re always talking about plans for the house they have together [Merton], how they will, in time, have their daughter [Horatia] come and live with them, how it will be a place for their children and their children’s children. This letter is actually full of incidental things, like her visiting such-and-such a person and going to church and liking the sermon.There is something about the everyday nature of it that’s really nice; the poignancy of what you know comes next. There is a lovely bit where she writes about Nelson coming back to “paradise Merton” and she’s kind of hoping for this moment that never arrives. It’s one of the tearjerker moments of the exhibition.

Emma Hamilton: Seduction and Celebrity is on at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich until April 17, 2017. Tickets are available online or in person. All photos in the post are c/o the NMM. For a glimpse at some of the objects as they are currently displayed, check out this post at Tincture of Museum.

There is also a stunning Emma Hamilton exhibition catalogue, edited by Quintin Colville, that I would highly recommend purchasing along with a copy of Alexander Korda’s That Hamilton Woman, for your viewing pleasure.

Thank you Kendra for this I will reread the article to delve deeper .At present I have just gathered the gist of it.Emma Hamilton a very interesting figure from British History.

Thanks, Audrey, She was very interesting and the exhibition is really enjoyable!

Its funny I just watched the movie over the weekend. How wonderful.

I’m glad I still receive your postings. I love history.

Thank you Kendra.

Thanks, Susan! I am to update more frequently in the future.

Kendra:

That necklace is beautiful!

I flew to London from the States for the exhibition and also to visit an old friend. I’m glad I did! Exhibition is fantastic not least the way they filmed an actress performing Emma’s Attitudes. I hope Kendra you can unearth the Vogue photos of Vivien doing the Attitudes, which I had not known about.

Hi Spencer,

I’m so glad you got to come over and see the exhibition. I also enjoyed the video of the attitudes recreations! I do have the Vogue photos and will post them once I get the photo gallery back up and running!

Thank you for sharing this fascinating article about Emma Hamilton, I really enjoyed it. I just wish I could view the exhibit, but it will be awhile before I visit London. Glad to see Emma is finally getting the recognition she deserves!

I’m glad she’s getting the recognition she deserves as well! A fascinating figure!

It is one one of my favorite films. I saved it on my DVR and will not erase it.

Poor Emma dying in prison,I almost cried and. I never cry.

Emma Hamilton at Naples !

“I am not strong enough to gaze at the light

of that lady, and do not know how to make a screen

from shadowy places, or the late hour:

yet, with weeping and infirm eyes, my fate

leads me to look on her: and well I know

I wish to go beyond the fire that burns me…”