I have a bunch of magazine and newspaper articles left over from my dissertation research, so I’ve decided to do “31 Days of the Oliviers.” Each day I will post a new article or blog post, ending with Vivien Leigh’s birthday on November 5. These articles (most of which have Vivien as the main subject) span the years 1937-1967 and come from both American and British sources. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I do!

I have a bunch of magazine and newspaper articles left over from my dissertation research, so I’ve decided to do “31 Days of the Oliviers.” Each day I will post a new article or blog post, ending with Vivien Leigh’s birthday on November 5. These articles (most of which have Vivien as the main subject) span the years 1937-1967 and come from both American and British sources. I hope you enjoy reading them as much as I do!

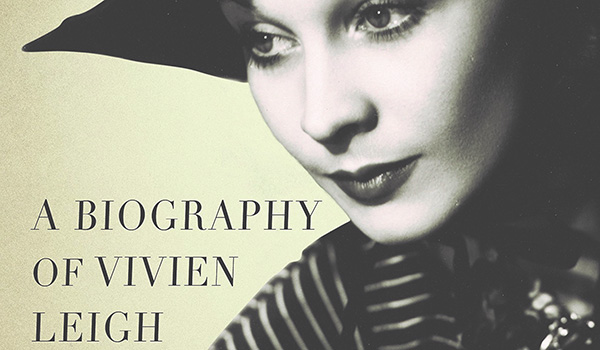

{Day 4} When Vivien Leigh landed the role of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind after a much-publicized search, she officially became studio property. As such, she was kept under close watch by Selznick. Details of her private life, particularly her relationship with Laurence Olivier, were kept under wraps as the publicity department generated stories–some true, some embellished–to build her new star persona. Journalists for various fan magazines were not granted one on one interviews with Vivien until after GWTW had finished filming.

This article, from Motion Picture magazine, shows how both star and studio collaborated to paint Vivien as woman as unconventional as the character she had just finished playing.

****

The Woman Behind Scarlett

by Roger Carroll

Motion Picture, February 1940

Just seven days before, on Friday the 13th of january, David O. Selznick had announced that Vivien Leigh–an English actress virtually unknown to America–would play Scarlett O’Hara. Ever since, Hollywood reporters had been clamoring to see for themselves whether or not she fitted Scarlett’s description. Now, at last, they were getting their wish.

The time was late afternoon. The place was the large reception room of the Early American cottage that Selznick provided as studio dressing quarters for his stars.

There, by appointment, a score of reporters had gathered–for a mass introduction. She was late. She was having a costume fitting but she was expected momentarily. Meanwhile, they were given a chance to fall under the spell of the setting. The room was early American, beautifully furnished. The lights were low. A low fire flickered in the fireplace.

Suddenly, an inner door opened and there, framed in the doorway, like a life-size Early American painting, stood a girl in white crinolines. The reporters hadn’t known what to expect but they hadn’t expected this. She stood there only for a moment before she stepped into the room to be introduced. But that moment was long enough. They all had time to be startled into the realization that here, in the flesh, was Scarlett.

There wasn’t any doubt about it. She had Scarlett vivid all over her face…the mischievous eyes…the tilt to her chin…the dark hair flecked with auburn…the slight, well-rounded figure. The crinolines only heightened the effect.

After the introductions, she perched on the arm of a chair answering questions–as unaware of being unconvetional as Scarlett would have been. She was as herself possessed as she was animated. As quick witted as she was frank. Like Scarlett. Someone asked her if she could talk with a Southern accent. Her answer, with the r’s softly slurred, sounded straight from Georgia, suh. That made the likeness complete.

Every reporter came away with the feeling that he had just met Scarlett O’Hara. I know, I was there. Ever since, I’ve wondered–as you will after you see Scarlett–just what it was like to be Vivien Leigh. The other day I went back to find out.

The setting was the same. The time was again late afternoon. Only the girl was different.

The girl sat curled up on a divan, her legs drawn up under her. And unquestionably shapely legs they were–unhidden by hoops. She was wearing a gray wool sports dress, within an inch of being knee high; unmistakably 1939. It had semi-military shoulders.

The girl wasn’t concerned with being dazzling. She was frankly natural.

She didn’t draw attention to her hair with an elaborate coiffure. She was wearing her hair loose in a long bob. This soft frame had en effect of making her face less severely oval than Scarlett’s.

She had a pert tilt to her chin, but it was a tilt of alertness, not coquettishness. There was a smile in her clear green eyes–but it was a smile of straightforward friendliness, not of mischievous challenge. She was animated–but her animation had no tense drive behind it. She was relaxed.

She was amused by these noticeable differences. “I’ve even lost my Southern accent,” she said, piquantly. “That took a bit of doing. I still find myself saying things like eether, when before Gone with the wind I said eyether. I suppose that will wear off in time.”

I asked her how it felt to be herself again, not Scarlett. Was she conscious of a let-down?

She shook her head. “All I’m conscious of is a blessed relief,” she said crisply. “I adore not working. I’m beginning to feel sane again–almost normal. For five months, except for five days and Sundays off, I had to work at being Scarlett from nine every morning to nine at night. Then, when I would fall into bed exhausted, I couldn’t sleep. Every nerve in my body was pounding. The last month or so, I had to take tonics to keep going. At the end, I was quite raving mad–ready for a lunatic asylum…I still wonder when I’ll have caught up on my sleep. Even now, every evening around nine, my eyelids start drooping.”

There are people that feel sorry for Vivien, on the grounds that, after Gone with the Wind, everything else will be an anticlimax for her. They are wasting their pity. She is getting a bigger kick out of ordinary living than she ever did before.

These people feel sorry for her because she will never again have such a triumph as Scarlett–the most coveted role in screen history. Ironically, she hasn’t yet had any sensation of triumph. What she had while she was making the picture was worry. And that’s what she still has, with the picture still to be released to the world at large.

She was about to go to Atlanta for the premier. “I dread it,” she said. “I’d like to be a million miles away, and not have to wonder how much of the applause is inspired by the picture, and how much is generated by the glamour of the event and the presence of the stars.”

Now, Scarlett wouldn’t feel that way. Scarlett would like nothing better than entering a theatre on a red carpet, conscious that all eyes were upon her. It would be a night of nights.

Here was a big psychological difference between Scarlett and Vivien. Were there any other big differences? Were there any ways in which they were alike?

“Well, Scarlett wasn’t the placid, easy-going type. Neither am I. I can’t let well enough alone. I get restless. Very. I have to be doing new and different things. I’m a very impatient person. And headstrong. If I’ve made up my mind to do something I can’t be persuaded out of it. My becoming an actress is an example of that.

“When Scarlett wanted something from life, she schemed about how to get it. That was her trouble. I just plunge ahead without looking. That’s my trouble. Every so often, I bump into stone walls–and have to pick myself up and climb over them.

“I’ll never be able to save like Scarlett. Money meant everything to her. Life was empty without it. It dominated everything she did. To me, time is what’s important. I’d rather have time to do many things than the money to do any one thing. It’s fortunate I feel that way, because the more I make, the less I’m able to save. When I first started on the stage and was making very little money, I seemed to get along all right. Now I’m earning the biggest salary I’ve ever earned, and I have to be strict with myself to get along. If I had come to Hollywood for the money, I’d have been better off to stay in England. What with the three income taxes I have now, I’m actually seeing less money as a star here than I did as a featured player at home. But–I want to stay.

“Scarlett had a strong sense of property. I have that a little. I like my own things around me very much. That’s one thing I have missed very much, being in Hollywood. Particularly my books, I collect them.

“She didn’t get along with other women. I do. At least, I think I do.

“She could take care of herself, when she had to. I think I could, too. Without such painful effort, I went to school for a time in Germany. That meant that, being a girl, I had to learn What Every Hausfrau Should Know. And hated it. That was one of the things that helped me make up my mind to become an actress.”

Vivien mused for a moment.

“I hope I have one thing that Scarlett never had–a sense of humour. I want some joy out of life. She never knew what joy was, except when she was very young.

“And she had one thing that I hope I never have–selfish, blind egotism. I understand that that’s something people sometimes get in Hollywood. I’m watching out for it.

“Scarlett was a fascinating person, nomatter what she did. But she was never a great person. She was too petty, too self-centered. She could never consider another person, for that person’s sake. She promised Ashley that she would look after Melanie. But she didn’t make that promise for Melanie’s good. She made it as part of her scheme to win back Ashley’s love.

“In may ways, she wasn’t a very admirable person. But one thing about her was admirable–her courage. She had more than I’ll ever have.”

That statement was open to question. How about her daring to invade Hollywood, test for the role of Scarlett though she was English, and play the role in the face of the uproar over Selznick’s having chosen her?

“But I didn’t come to Hollywood to try for the role. I came on a visit. When a test was offered me, it was a challenge. Was it something I was equipped to do? When the role itself was offered me, that was another challenge. I wasn’t the least bit surprised or annoyed by the resentment against me. I thought of it as something I could overcome, if I tried hard enough. During the picture, many times, I would ask myself, half-paralyzed, ‘What have I got myself in for?’ But I had gone too far then to turn back.”

What was the most difficult scene? That required several minutes of thought.

“The one in which Scarlett realizes that for eight years, while she has been telling herself she loved Ashley, she has really loved Rhett. Margaret Mitchell needed thirty or forty pages in the book to convince the reader of the reasonableness of her sudden realization. I had to try and persuade audiences of the same thing in one scene. Nothing I had to do was more difficult than that.”

For days at a time, during the making of the picture, the set would be closed to visitors–at her request. That sounded to Hollywood like temperament. Was it?

“No. Pure and simple jitters. Days at a time, we had no fixed script. Mr. Selznick was constantly working on the script, you see, to make it as perfect as possible. often we would get our dialogue practically page by page. Difficult scenes would come up, and I would have little preparation for them–no confidence, even, in my being able to remember my lines on such short notice. Having strangers on the set, on those days, was like having onlookers in the theatre during rehearsals for a stage play. You don’t want an audience until you are sure of what you are to do. At least, I don’t.

“One reason why Pygmalion was so good was that it was rehearsed in its entirety before the camera ever turned. If the principal players of every picture could rehearse before production started, performances couldn’t help improving. The more you rehearse any play, the better it becomes.”

Gone with the Wind or no, Vivien still likes working on the stage better than working on the screen. The theatre’s devotion to rehearsals is one reason. The other reason is: “You have the whole day free, to be out in the air and the sunshine. Working all day on a movie set, you never see the sun. Think of what you miss.”

She hasn’t found picture making in Hollywood much different from picture making in England. She hasn’t felt like a stranger here. “People have been very kind–very quick to be friendly.” She has a knack for making friends, herself.

The make-up experts look upon her with deep, dark suspicion, wondering if she doesn’t trust them. She insists on putting on her make-up herself. It isn’t a matter of trust. It’s a matter of habit, carried over from the stage. Also, if she can come to the studio in the morning, all made up for a day’s work, she doesn’t have to arrive much before nine o’clock.

She is one English star who doesn’t take tea. SHe doesn’t like tea. Neither does she like coffee. She drinks milk, with honey in it. (The honey is a bit of an energy tonic.) She doesn’t diet. She has a “ravenous” appetite. For practicaly everything except salads. She doesn’t enjoy those. There isnt enough rabit in her.

She is wildly crazy about clothes, all kinds, from bustles to slacks. She likes furs (as what girl doesn’t?) All kinds of furs, except chinchilla. “Thats a good thing, what with chinchilla costing about $25,000 per coat.”

She rents a small, furnished stucco house, typically Californian–and likes it. Although she does complain bitterly that she hasn’t room in it for her books she has collected, just since her stay in Hollywood.

The house has a small swimming pool, which she uses. She plays tennis–“very badly.” She plays darts–ditto. Her favorite sport is golf–“but I’m not good at that, either.” All-around-athlete Leigh, they call her. She plays piano. She does a great deal of reading. She likes dancing but she doesn’t like nightclubs. “They’re crowded and hot, and I get sleepy in them.” She dances well. She used to do the aesthetic kind. She likes large parties only at her own house–where she knows everybody.

In person, she talks just as crisply and briskly as she does in Gone with the Wind. There have been a few scattered criticisms of her rapid dialogue delivery. “But the impression that Southerners talks slowly is a misimpression. Listen sometime to educated Southerners talk, as I had to, to get their manner of speaking. That soft slur of the r’s fools you into thinking of them as drawling.”

She won’t talk crisply or otherwise, about Laurence Olivier–who, the columnists say, she is going to marry. The columnists are decidedly premature. Neither of them has yet taken steps to divorce their present mates. That makes Vivien still officially married to Leigh Holman, London barrister. They have a five-year-old, Suzanne.

As soon as she finished the last scene of Gone with the Wind, Vivien hopped a plane east and raced across the Atlantic to see her little girl, check up on the war rumors. England was calmer than it had been before the Munich conference. No one thought there was going to be a war. Reassured, Vivien came back alone. No matter how much she wanted Suzanne with her, Suzanne was happy in England. She didn’t want to tear the little girl loose from the security and surroundings she had always known…Then, three weeks after Vivien’s return, war was declared. And Suzanne had to be uprooted from familiar scenes. “Her father has her now in Devonshire, which is safe. There are no industries there, no targets for bombs.”

Vivien seems destined to stay in America for a long, long time. She has made good as Scarlett. Also, she has a long-term contract with David O. Selznick who regards her (rightly) as a very valuable property, and will loan her out when she has nothing to do on the home lot. She also has a one-picture-a-year contract with her old boss, Alexander Korda. But, until further notice, he is making pictures for the British government and cant use Vivien. That makes her America’s exclusively. Except that she is doing her bit for England with that chunk of income tax.

She is about to go to work again–on loan to MGM, for Waterloo Bridge. And she’s happy about it, and the chance to play a character completely different from Scarlett. “Only, I do with it were a bit lighter story. People will go out in blackouts to see a light comedy and laugh, but will they go out to cry?”

That’s Vivien Leigh–the woman behind Scarlett.

thank you for posting these articles all this month! i have been enjoying them immensely!! 🙂

This was a very good read. Thank you for sharing:)

Thank you so much for this wonderful article!!!