This post was written for the Classic Movie History Project Blogathon co-hosted by Movies Silently, Once Upon a Screen and Silver Screenings.

*****

Since January, I’ve been employed as the Archivist for the estate of photographer James Abbe (I mentioned this a couple posts ago). With approximately 5,000 items including negatives, original prints, letters, scrapbooks and more, it’s a big and exciting job scanning and cataloguing this treasure trove. But we’re making headway and eventually the estate hopes to transform it into a searchable, online archive dedicated to selling prints and providing information to researchers.

James Abbe grew up in Newport News, Virginia where he became interested in photography at an early age. In the 1900s Newport News was a busy shipping town and Abbe was often found wandering the streets with his handheld fold out Kodak, capturing events of local interest. He became so prolific that he was dubbed “The boy photographer of Newport News.”

In 1917, after a successful breakthrough into professional photography for the Washington Post, Abbe moved to New York where he set up his own studio on West 67th Street. It was there that he was introduced to the film world. His first film star subject was Marguerite Clark whose screen credits included The Crucible (1914), The Seven Sisters (1915) and Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1918). He also photographed several actors who appeared on the New York stage before making a break in films, including Fred Astaire (and his sister/dancing partner Adele), Talulah Bankhead and Mae West.

As National Portrait Gallery curator Terence Pepper has noted, Abbe’s “most enduring relationship in the film world” was with Lillian Gish and her sister Dorothy. Indeed, many original prints of the sisters taken separately in New York, London, and Paris during the 1920s have surfaced in the archive. He first photographed Lillian in his New York studio for the 1917 D.W. Griffith film Broken Blossoms in which Gish played Lucy, the poor girl in London’s gritty East Wend who falls in love with a Chinese man. Abbe’s sittings with Gish led to a working relationship with director D.W. Griffith who produced films out of his studio in Mamaroneck, New York. At Mamaroneck, Abbe worked as a portrait photographer or stills photographer (sometimes both) on several of Griffith’s films.

In 1920, Abbe moved on to Hollywood where he worked closely with Mack Sennett at Keystone Studios, and contributed photographs to several fan magazines. He even had his own feature, “The Photographer Takes the Stage,” in Motion Picture Classic, a sister publication of other popular fan magazines like Shadowland and Beauty. Several future Hollywood big shots were employed by Sennett during Abbe’s tenancy in Hollywood. Among Abbe’s future-famous subjects were Gloria Swanson, Carole Lombard and Wallace Beery. He also captured legends of their own time like Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood, Charlie Chaplin during The Pilgrim, and Mary Pickford for Tess of the Storm Country and Suds.

Abbe’s film photography was not limited to the United States. He was first and foremost a freelance photojournalist and as the years went on he built up a roster of big name magazines and newspapers that accepted his photographic essays and often kept his photographs on file. In London, he contributed to The London Magazine, The Tatler and The Sketch. A notable essay that we’ve come across thus far was one he did about his time spent with director Herbert Wilcox at Elstree Studios where Dorothy Gish was employed for several films during 1925-1926. In Berlin, he photographed luminaries like F.W Murnau and Emil Jannings at UFA, frequently contributing to Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung. In Moscow, his subjects included Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein.

Although the breadth of Abbe’s work spans several decades and subjects ranging from theater to ballet, politics to war photography, his involvement in filmmaking during the era of silent cinema is significant enough to warrant discussion on its own. Here, then, is a selection of film-related images scanned from the archives of James Abbe.

I’d love to know your thoughts on these photographs, and if you’re big into silent film and recognize people or dates that we have yet to identify, please let me know!

Learn more about the Abbe Archive on Facebook.

Charlie Chaplin in The Pilgrim (1922), signed by Abbe in his signature crayon

Abbe (right) with friends Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford in France circa 1924. Photographer unknown.

Tom Mix wearing his trademark cowboy attire, photographed in his suite at the Aldon Hotel in Berlin, 1925. Abbe managed to get Mix to pose with theatre impresario Max Reinhardt in another photo, despite him having never heard of Mix.

Pre-Hollywood: Tallulah Bankhead photographed on her arrival in New York in 1918. She made her debut in The Squab Farm that year.

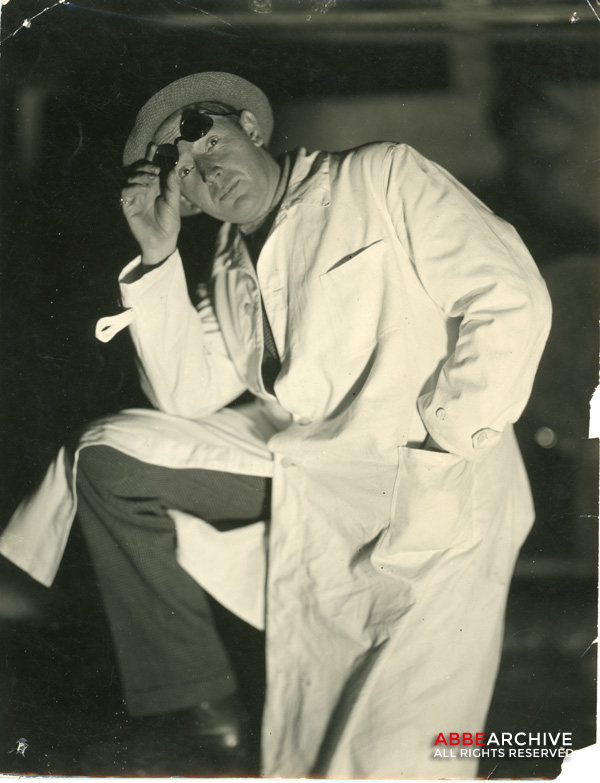

Legendary German film director Friedrich Wilhelm (F.W.) Murnau photographed at UFA studios in Berlin cira 1926

Russian actor Erast Pavlovich Garin in Gogol’s Revisor, directed by Vsevolod Meyerhold. Moscow, 1927. Abbe called Garin “A cross between John Barrymore and Harold Lloyd.”

American director D.W. Griffith photographed at his Mamaroneck studios in New York while filming Orphans of the Storm, 1919.

American film and stage actress Jeanne Eagels in David Belasco’s “Daddies,” 1919. A variant pose from this sitting was the first photograph to be published on the cover of the Saturday Evening Post.

Ivor Novello and Gladys Cooper in a still from Bonnie Prince Charlie (Charles Calvert, 1923)

Theatrical producer C.B. Cochran with British songstress Jessie Matthews, star of Rogers and Hart’s “Ever Green,” photographed on stage at the London Pavilion circa 1930. Matthews would later make a smash hit singing “Over My Shoulder” in Victor Saville’s film adaptation.

Abbe’s (3rd) wife, former Ziegfeld Folly Polly Platt (Shorrock) as an extra in the 1922 film The White Sister. The photograph was taken on location in Italy.

American actress Dorothy Gish (seated, center) and the crew of Herbert Wilcox’s London (1926) take a break during location shooting in England.

Irene Bordoni and Jack Buchanan take a smoke break on the set of their first talking picture, Paris (1929). Director Clarence Badger can be seen in the sound recording box behind them.

Portrait of American silent film star Theda Bara. Photo is undated.

Still of Richard Barthelmess and Lillian Gish in Way Down East (D.W. Griffith, 1920)

Louise Fazenda, Wallace Beery and unidentified woman in a publicity portrait for Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios. Fazenda (left) is in costume for her 1920 film Down on the Farm.

Undated portrait of Marion Davies who was then starring in a revue at New York’s Amsterdam Roof.

The Latin Lover Rudolph Valentino and wife Natacha Rambova in a publicity portrait for their celebrated dance tour for Mineralava Clay Company, 1923.

America’s Sweetheart Mary Pickford photographed in Paris circa 1924.

Bobbie Vernon, Gloria Swanson and an unidentified Mack Sennett player. The photo has been marked up for publication alongside a three-column story on Swanson’s life in an unspecified magazine or paper.

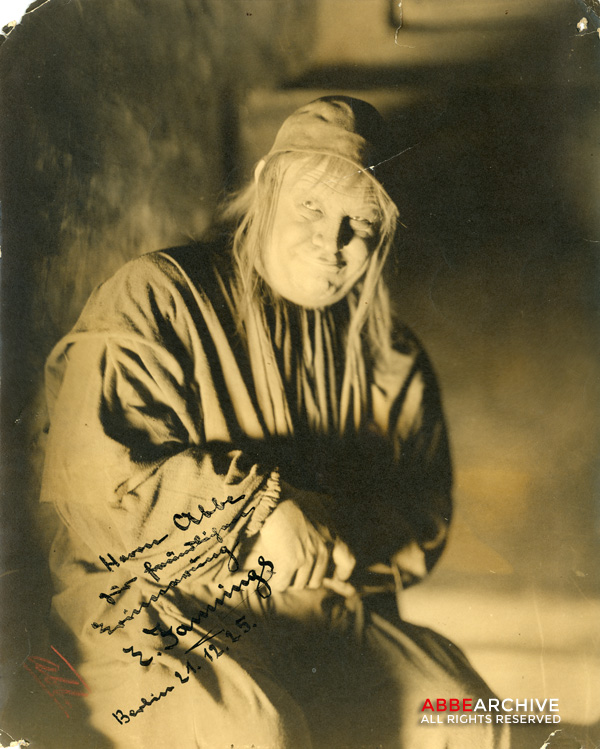

Emil Jannings in costume as Faust, photographed at UFA studio in Berlin, 1925.

Lillian Gish in costume for her role in The White Sister. Photographed on location in Italy in 1922. Notice the grates in the pavement.

Undated portrait of American actress Constance Talmadge.

Behind the scenes on a film shoot with director Herber Wilcox and crew (likely the 1926 film London at Elstree Studios). The man in the top hat on the right appears to be Adelqui Millar (Adelqui Migliar).

American actress Betty Compson and British actor Clive Brook in The Royal Oak (Maurice Elvey, 1923)

Dorothy Gish publicity portrait for Nell Gwyn (Herbert Wilcox, 1926)