Since her centenary in 2013 Vivien Leigh has been enjoying an extended moment in the spotlight and I am sure I’m not alone when I say it’s pretty great. She has been recognised through exhibitions at the National Portrait Gallery, V&A, and Topsham Museum. Several one-woman plays have been staged. Actress Natalie Dormer is adapting my own book into a TV series. Vivien’s family made millions from a Sotheby’s sale of belongings from her estate. And Manchester University Press published a compilation of essays examining various facets of her life and career. It’s wonderful that, despite having died half a century ago, interest in Vivien is still going strong.

Tag: book corner

books interviews laurence olivier

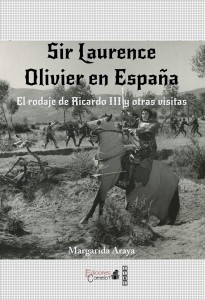

Interview with Laurence Olivier author Margarida Araya

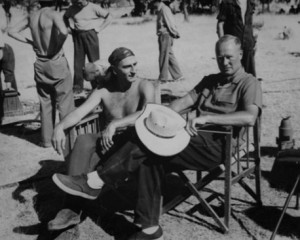

Richard III is one of Laurence Olivier’s most critically acclaimed films, both as an actor and director. Filmed in Spain in 1954 with interiors shot in England, it is the third film in what is now known as the Olivier Shakespeare Trilogy (out on Criterion Collection). While information about Olivier’s life in England is abundant, his time in Spain is less well-known–until now.

Here, Tanguy Deville interviews theatre historian, author, and Laurence Olivier expert Margarida Araya about her debut book, Sir Laurence Olivier in Spain.

*****

Tanguy Deville: Can you introduce yourself briefly and tell us how you became interested in Laurence Olivier?

Tanguy Deville: Can you introduce yourself briefly and tell us how you became interested in Laurence Olivier?

Margarida Araya: I’m from Barcelona and I’m a translator and an Air Navigation Technician. I started to get really interested in Laurence Olivier (I had seen some films before) when I watched The Entertainer. It contained everything I liked: theatrical references, a looser character and a great performance. Then I started to look for information/photos of him on the Internet and discovered what a glamorous couple he and Vivien Leigh made.

TD: How did the idea of the book come about?

MA: I always love to investigate things. I started to investigate (through newspaper libraries) if LO had even been to Barcelona. Then I started to find about the shooting of Richard III near Madrid and the Oliviers’ holiday in Andalucia.

When I had compiled a lot of information I decided to create a small site to share it. I kept on investigating (travelling to Madrid and to the British Library in London) and after discovering some interesting facts I thought that they deserved to be published in a book. So I sent my proposal to different publishing houses and then a friend put me in contact with Camelot.

When I had compiled a lot of information I decided to create a small site to share it. I kept on investigating (travelling to Madrid and to the British Library in London) and after discovering some interesting facts I thought that they deserved to be published in a book. So I sent my proposal to different publishing houses and then a friend put me in contact with Camelot.

TD: We know a lot about the Oliviers in Italy, and in France. Their stay in Spain is less well-known; very few biographers have investigated it. Why is that?

MA: They only came to Spain on holiday once so there is much more documentation of them in Italy.

TD: How did you work on the research?

MA: My main research has been through Spanish newspaper libraries (online and physical). I travelled to Madrid to visit the zone where they shot Richard III and I contacted several towns in the zone, but just one (Torrelodones) gave me feed-back and helped me answer a couple of questions. I also went to the British Library in London where I could read Olivier’s personal diaries.

MA: My main research has been through Spanish newspaper libraries (online and physical). I travelled to Madrid to visit the zone where they shot Richard III and I contacted several towns in the zone, but just one (Torrelodones) gave me feed-back and helped me answer a couple of questions. I also went to the British Library in London where I could read Olivier’s personal diaries.

TD: Were the Oliviers big stars in Spain at the time?

MA: The Spanish press was quite disconnected from the rest of the world; they hardly  knew anything about the Oliviers. They only knew them from being the stars of Hamlet and Gone With the Wind. In my book I reproduce some original interviews and they are very naive.

knew anything about the Oliviers. They only knew them from being the stars of Hamlet and Gone With the Wind. In my book I reproduce some original interviews and they are very naive.

TD: Why did Olivier decide to film Richard III in Spain?

MA: After filming Henry V in Ireland, he looked for a location with better weather. Spain was cheap and had a lot of sun. The only problem he found was that the grass was too yellow to look like Bosworth…

TD: The Oliviers made many trips to Spain. What did they do and who did they meet there?

MA: There isn’t much information about their visits in the Spanish press. These were pre-paparazzi times! They met Lola Flores, the flamenco dancer, during the shooting of Richard III. During their holiday in Andalucia they also meet Antonio, another flamenco dancer, so we can guess they really liked flamenco! They visited several Andalucian towns and they even went to the cinema to see a Spanish movie.

TD: At the time of Richard III and later in the ’50’s, Spain started to become a great place for filming…

MA: Yes, and Olivier claimed his was the first international production to do it. After him came Orson Welles, the Samuel Bronston productions and Kubrick’s Spartacus*, for example.

(*Olivier didn’t come to Spain for the Spartacus filming. They used a body double during the battle scene.)

TD: During the writing of your book and the research did you make some interesting discoveries?

MA: I can’t tell you about the main discovery, it’s a secret! (It will surprise Spaniard readers.) But I can tell you that in many interviews LO said he had been in Spain before August 1954, and I couldn’t find any reference of this trip. One day, by chance and through a Marilyn Monroe book, I saw a photo of him standing in front of a Spanish sign. I was lucky to find the Spanish magazine that had published that photo. They even interviewed him. This visit was confirmed in his diaries.

MA: I can’t tell you about the main discovery, it’s a secret! (It will surprise Spaniard readers.) But I can tell you that in many interviews LO said he had been in Spain before August 1954, and I couldn’t find any reference of this trip. One day, by chance and through a Marilyn Monroe book, I saw a photo of him standing in front of a Spanish sign. I was lucky to find the Spanish magazine that had published that photo. They even interviewed him. This visit was confirmed in his diaries.

TD: Richard III is considered to be the greatest part of Olivier’s (specially on stage). What is your opinion of that movie today?

MA: When I first saw the movie it surprised me to see it had a comical tone and I immediately fell in love with Richard. I think it’s a combination of his two previous Shakespearean films. The first part is very theatrical and then, we have the ‘Spanish’ part with a lot of real action. The cast and the rhythm are great. I’ve seen other Richard III versions but I stick with Olivier’s.

TD: After their divorce, did Larry go back in Spain? What about Vivien?

MA: Yes, Larry came back to Spain many times, with Joan Plowright, to spend different summers in the Balearic Islands. He was also in Costa Brava for two days filming Nicholas and Alexandra.

I centered my research on Larry so I can’t tell you for sure if Vivien came back to Spain, but I haven’t seen her name in any subsequent document.

*****

Sir Laurence Olivier en España tells us why the British actor and director Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) chose “those stunted Spanish trees and the silver grass” to shoot part of his film Richard III near Madrid in 1954. Despite its secrecy, and thanks to certain documentation such as Olivier’s personal diaries, some mysteries of the shooting are revealed. We also have access of several interviews given by Olivier and his then wife, the actress Vivien Leigh, to the Spanish press in 1954 as well as on his later visit, on holiday in Torremolinos, in 1957.

Sir Laurence Olivier en España tells us why the British actor and director Laurence Olivier (1907-1989) chose “those stunted Spanish trees and the silver grass” to shoot part of his film Richard III near Madrid in 1954. Despite its secrecy, and thanks to certain documentation such as Olivier’s personal diaries, some mysteries of the shooting are revealed. We also have access of several interviews given by Olivier and his then wife, the actress Vivien Leigh, to the Spanish press in 1954 as well as on his later visit, on holiday in Torremolinos, in 1957.

Sir Laurence Olivier en España is published by Camelot and is available in Spanish, with an English language version coming soon.

Margarida Araya also runs the Sir Laurence Olivier Stage Work website and the wonderful Sir Laurence Olivier Fan Page on Facebook.

Book Diary 2015

*Header image by Nina’s Clicks

I’ve got a few New Year’s resolutions, although some of them are New Years hopes. But one of the things I’m determined to achieve from the outset is to read more books for fun. Last year was the first time I was able to do this in ages, although I neglected to keep a written list. (Highlights included Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild by David Stenn, In The Woods by Tana French, The Romanov Sisters by Helen Rappaport, Garden of Dreams: The Life of Simone Signoret by Patricia DeMaio and Brando’s Smile by Susan Mizruchi) That changes this year, dammit! I’ll be keeping track on Goodreads, Instagram and will do my best to keep this log updated here.

So far, so good!

1. Alice + Freda Forever: A Murder in Memphis by Alexis Coe (historical non-fiction; true crime)

2. My Name Escapes Me: The Diary of a Retiring Actor by Sir Alec Guinness (memoir)

3. Neverhome by Laird Hunt (historical fiction; American Civil War)

4. Of All Places! by Patience, Richard and Johnny Abbe (memoir)

5. The Romanovs: The Final Chapter by Robert K. Massie (non-fiction; Russian history)

6. Wild by Cheryl Strayed (memoir; travel)

7. All the Pretty Horses by Cormac McCarthy (fiction)

8. Stiff: The Curious Lives of Human Cadavers by Mary Roach (non-fiction; science)

9. Spook: Science Tackles the Afterlife by Mary Roach (non-fiction; science)

10. All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr (fiction)

11. Nicholas and Alexandra by Robert K. Massie (biography; Russian history)

12. Swamplandia! by Karen Russell (fiction)

13. The Great Hollywood Portrait Photographers by John Kobal (film studies; photography)

14. A Girl Walks into a Bar by Rachel Dratch (comedy; memoir)

15. Follies of God: Tennessee Williams and the Women of the Fog by James Grissom (memoir; theatre)

16. In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex by Nathaniel Philbrick (historical non-fiction)

17. An Anthropologist on Mars by Oliver Sacks (psychology; neurology)

18. Leaving Time by Jodi Picoult (fiction)

19. The Natty Professor by Tim Gunn (memoir)

20. The Revenant: A Novel of Revenge by Michael Punke (historical fiction)

21. The Girl on the Train by Paula Hawkins (fiction; thriller)

22. In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin by Erik Larson (historical non-fiction)

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠

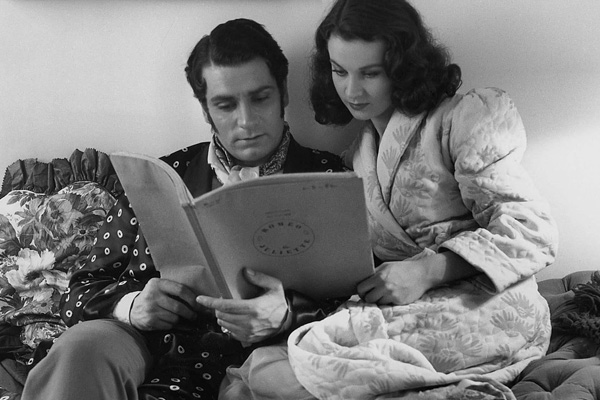

Commonplace Books of Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier

In December 1946, Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier were chosen by Strand magazine in London to contribute literary quotes from their personal Commonplace Books. Commonplace Books (commonly referred to today as “inspiration journals”) are blank notebooks that differ from traditional diaries in that they’re not meant to record life events in a chronological order. Rather, they’re a random hodgepodge of thoughts, quotes and passages from books, sketches, recipes, etc. that made an impression in the moment.

Strand printed a running series called “The Commonplace Books of…” where “Every month [they] publish quotations from the Commonplace Books of people whose names you know and whose wide reading you envy.” While the choice of works the Oliviers quote from may seem familiar from what we have read about them in biographies, what is interesting is what these particular quotes reveal about their individual personalities. To me, Vivien seems like a dreamer, whereas Larry Olivier comes off as a romantic.

What do you think of this list?

Vivien Leigh

Entries in my Commonplace Book are very varied and I am continually adding to them. My favorite quotations include “The Cloths of Heaven” by W. B. Yeats:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths

Enwrought with gold and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths,

Of night and light and the half light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet;

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams

And that memorable sentence on the death of William III, the last sentence in J. L. Motley‘s “Rise of the Dutch Republic”:

As long as he lived, he was the guiding star of a brave nation, and when he died the little children cried in the streets.

In humorous prose I like the entry of April 23rd in “The Diary of a Nobody” by George and Weedon Grossmith:

Mr. and Mrs. James (Miss Fullers that was), came to meat-tea, and we left directly after for the Tank Theatre. We got on a bus that took us to King’s Closs, and then changed to one that took us to the Angel. Mr. James each time insisted on paying for all, saying that I had paid for the tickets and that was quite enough.

We arrived at the theatre, where, curiously enough, all our bus-load except and old woman with a basket seemed to be going in. I walked ahead and presented the tickets. The man looked at them, and called out “Mr. Willowly! Do you know anything about these?” holding up my tickets.

The gentleman came to, came up and examined my tickets and said: “Who gave you these?” I said rather indignantly: “Mr. Merton, of course.” He said: “Merton? Who’s he?” I answered rather sharply, “You ought to know, his name’s good at any theatre in London.” He replied: “Oh! is it? Well it ain’t no good here. These tickets, which are not dated, were issued under Mr. Swinstead’s management, which has since changed hands.”

While I was having some very unpleasant works with the man, James, who had gone upstairs with the ladies, called out: “Come on!” I went up after them, and a very civil attendant said: “This way, please, Box H.” I said to James: “Why, how on earth did you manage it?” And to my horror he replied: “Why, paid for it, of course!”

This was humiliating enough, and I could scarcely follow the play, but I was doomed to still further humiliation. I was leaning out of the Box, when my tie – a little black bow which fastened on to the stud by means of a new patent – fell into the pit below. A clumsy man not noticing it, had his foot on it for ever so long before he discovered it. He then picked it up and eventually flung it under the next seat in disgust. What with the Box incident and the tie, I felt quite miserable. Mr. James, of Sutton, was very good. He said: “Don’t worry – no one will notice it with your beard. That is the only advantage of growing one that I can see.” There was no occasion for that remark, for Carrie is very proud of my beard.

To hide the absence of the tie I had to keep my chin down the rest of the evening, which caused a pain in the back of my neck.

Of many favorite passages in Shakespeare, I like best of all the last speech of Oberon in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” from which these lines are taken:

Never more, hair, nor scar,

Nor mark prodigious, such as are

Despised in nativity,

Shall upon their children be.

And the 29th Sonnet, beginning,

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s

eyes,

I alone be weep my outcast state…

I have read a great deal of Thomas Hardy and Dickens. The chapter on sheep-shearing in “Far from the Madding Crowd” ranks, I think, among the finest descriptive writings. With these I also place the beginning of “The Battle of Life” from Dickens “Christmas Books” – the description of the field from which “the painted butterfly took blood into the air upon the edges of its wings.”

For pure joy of reading I choose the reunion scene at the end of “Pickwick Papers”:

…. The coaches rattled back to Mr. Pickwick’s to breakfast, where little Mr. Perker already awaited them.

Here, all the light clouds of the more solemn part of the proceedings passed away; every face shone forth joyously, and nothing was to be heard but congratulations and commendations. Everything was so beautiful! The lawn in front, the garden behind, the miniature conservatory, the dining-room, the praying room, the bedrooms, the smoking room, and above all the study with its pictures and easy chairs, and odd cabinets, and queer tables, and books out of number, with a large cheerful window opening upon a pleasant lawn and commanding a pretty landscape, just dotted here and there with little houses almost hidden by trees; and then the curtains, and the carpets, and the chairs, and the sofas. Everything was so beautiful, so compact, that there really was no deciding what to admire most.

And in the midst of all this stood Mr. Pickwick, his countenance lighted up with smiles, which the heart of no man, woman, or child could resist: himself the happiest of the group, shaking hands…over and over again with the same people, and when his own were not so employed, rubbing them with pleasure; turning round in a different direction at every fresh expression of gratification or curiosity, and inspiring everybody with his looks of gladness and delight.

And, finally, a quotation from Plato which is, I think, particularly appropriate at the present time:

Then tell me, O Critias, how will a man choose the ruler that shall rule over him? Will he not choose a man who has first established order in himself, knowing that any decision that has its spring from anger or pride or vanity can be multiplied a thousand fold in its effects upon the citizens?

Laurence Olivier

Nearly all of my leisure reading is Shakespeare. May passages from the works of that greatest of poets come to my mind, notably Burgundy’s speech in “Henry V,” Act V, and part of the concluding chorus in the Epilogue, which runs:

Thus far, with rough and all-unable pen,

Our bending author hath pursued the story,

In little room confining mighty men,

Mangling by starts the full course of their glory.

Small time, but in that small most greatly

lived

This star of England: Fortune made his sword;

By which the world’s best garden he achieved,

And of it left his son imperial lord.

Here are four other of my favorite sonnets from Shakespeare’s plays:

Brutus in “Julius Caesar”

(Act IV, Scene iii)

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such full sea we are now afloat;

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

The Boy’s Song in “Measure for Measure”

(Act IV, Scene i)

Take, O, take those lips away,

That so sweetly were forsworn;

And those eyes, the break of day,

Lights that do mislead the morn:

But my kisses bring again, bring again;

Seals of love, but seal’d in vain, seal’d in vain.

Holofernes in “Love’s Labour’s Lost”

(Act IV, Scene iii)

This is a gift that I have, simple, simple;

a foolish extravagant spirit, full of forms,

figures, shapes, objects, ideas, apprehensions,

motions, revolutions: these are begot in the

ventricle of memory, nourished in the womb

of pia mater, and delivered upon the mellowing

of occasion. But the gift is good in those

to whom it is acute, and I am thankful for it.

The First Murderer in “Macbeth”

(Act III, Scene iii)

The west yet glimmers with streaks of

day:

Now spurs the lated traveller apace

To gain the timely inn; and near approaches

The subject of our watch.

I am also very fond of the two songs dedicated to Spring and Winter which come at the end of “Love’s Labour’s Lost.” Of other poets, Keats has always been one of my favorites. There is a delightful stanza from his “Ode to a Grecian Urn”:

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

In prose, I share with my wife a liking for both ‘The Diary of a Nobody’ and Hardy’s “Far from the Madding Crowd.” I am an admirer of Rupert Brooke, especially the first half of that poem “The Great Lover,” which begins:

I have been so great a lover: filled my days

So proudly with the splendour of Love’s praise,

The pain, the calm, and the astonishment,

Desire illimitable, and still content,

And all dear names men use, to cheat despair,

For the perplexed and viewless streams that bear

Our hearts at random down the dark of life.

My favorite quotations would be incomplete without the first stanza of Gray’s “Elegy”

The curfew tolls the knell of a parting day

The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

– an this memorable verse by William Allingham:

Four ducks on a pond,

The blue sky beyond,

White clouds on the wing.

What little thing

To remember for years,

To remember with tears.

Add these books to your shelf:

- The Collected Poems of William Butler Yeats (Wordsworth Poetry Library)

- The Rise of the Dutch Republic by John Lothrop Motley (Free on Kindle)

- Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith (Wordsworth Classics)

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (The Oxford Shakespeare)

- The Sonnets and A Lover’s Complaint by William Shakespeare (Penguin Classics)

- Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy (Penguin)

- A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Writings by Charles Dickens (Penguin Classics)

- The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (Penguin Classics)

- Timaeus and Critias by Plato (Penguin Classics)

- Henry V by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library)

- Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library)

- Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare (Modern Library)

- Love’s Labour’s Lost by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library)

- Macbeth by William Shakespeare (Pelican)

- The Complete Poems of John Keats (Penguin) | Bonus material: Bright Star (Jane Campion, 2010)

- The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke (Pomona Press) | Bonus material: Song of Love: The Letters of Rupert Brooke and Noel Olivier by Pippa Harris (Crown)

- The Poetry of Thomas Gray (Portable Poetry)

- The Collected Poems of William Allingham (CreateSpace)

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠

Book Corner: Ruth’s Journey

Ruth’s Journey

The Authorized Novel of Mammy from Margaret Mitchell’s Gone With the Wind

by Donald McCaig

WARNING: This post contains spoilers

In November of last year, the British Film Institute released Gone With the Wind in cinemas across the United Kingdom. The event was the end cap of a successful season in London commemorating the 100th birthday of the film’s star, Vivien Leigh. It also coincided with the theatrical release of Steve McQueen’s critically acclaimed film 12 Years a Slave. Finally, many said, the film business was ready to tell a story that showed one of America’s most shameful institutions in harsh and uncomfortable detail. Why then, would the BFI re-release a film that whitewashed the treatment of slaves during the antebellum era? Guardian contributor John Patterson, who completely missed the point, asked, “Are they looking to generate coattail ticket receipts from the controversy attending Steve McQueen’s harrowing and violent epic? Do they think some retirement-home demographic of faded southern belles and elderly white racists will emerge, stooped and wrinkled, to reclaim it one last time?”

The comparisons to McQueen’s film reared their heads again during the 2014 Oscars when the Academy awkwardly decided to celebrate the glory days of 1939 by ignoring the film that swept the awards that year – and continues to be the highest grossing film of all time – and instead paying homage to the more family-friendly and non-controversial classic The Wizard of Oz. But here’s the thing: Gone With the Wind won’t go away anytime soon. This doesn’t mean that the book and film (both produced upward of 100 years ago) shouldn’t be open to controversy and discussion, or even outrage and disgust. But none of that will stop people from seeking it out and probably even enjoying it. It’s too entrenched in popular culture.

Gone With the Wind is more than a single novel or a single film – it’s an ongoing industry. The Mitchell estate understands that more than anyone, which is why, just a month after 12 Years A Save picked up the Academy Award for Best Picture, Simon & Schuster announced that they would be publishing a new, authorized prequel to Margaret Mitchell’s novel. Ruth’s Journey, authored by Donald McCaig (Rhett Butler’s People, also authorized), would tell the story of Scarlett O’Hara’s faithful Mammy (played by Hattie McDaniel in the film – a performance that made her the first African American Oscar winner). It was strategic timing. The Mitchell estate seemed to be capitalizing on the continued popularity of Gone With the Wind, as well as the controversy surrounding it. In theory, anyway…

On the island of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) at the turn of the 19th century, a slave rebellion threatens French occupation. Solange Escarlette Fornier has left the mother country with her new husband, Augustin, to claim a once-prosperous sugar plantation. “Though Solange was young, she wasn’t beautiful.” (If you haven’t guessed already, Solange is Scarlett O’Hara’s grandmother) She wears the pants in the family and doesn’t care for her husband’s weak countenance (Charles Hamilton, anyone?). While on a scouting mission to capture the runaway, rumored lover of General Rochambeau’s nephew, Captain Augustin’s troop comes across a small shack where they find a slaughtered African family and one lone survivor. The little girl is taken home and presented to Solange who proclaims her beautiful and gives her a name.

Thus begins Ruth’s journey. She follows her new master and mistress to Savannah, stays with Solange through the death of her first husband and marriage to her second, and falls in love with free coloured stair builder Jehu Glen. With Solange’s permission she moves to Charleston, marries and has a daughter, Martine. She finds work as a housemaid at the Ravenel plantation where she is treated kindly. There’s just one problem: Jehu neglects to emancipate Ruth and Martine (because he bought Ruth from Solange, she’s is technically his property and seems strangely okay with that). Unfortunately Jehu dies just before South Carolina makes emancipation a legislative decision, so Ruth and Martine are sent to the auction block. This is not the end of Ruth’s story, of course. She is saved by Master Ravenel and continues to serve as Mammy of the household – until Jack Ravenel becomes a widower and tries to drunkenly take advantage of his indentured servant, at which point Ruth gathers her gumption and tells her Master she’s leaving (he seems strangely okay with that). She returns to Savannah just in time for Solange’s wedding to Pierre Robillard, rejoins the family, and from there goes on to Tara where she serves as Mammy to the three O’Hara girls.

The real challenge any author faces in writing a derivative work of Gone With the Wind is trying to be original within the parameters set down by Margaret Mitchell so that fans recognise it as part of the same canon. Prior to the release of his previous book Rhett Butler’s People, McCaig admitted to not having read Gone With the Wind. It’s clear that he has by now, and he creates backstories of some of the characters mentioned in Mitchell’s novel. For example, we learn that Pierre Robillard is Solange’s third husband and that their daughter Ellen is only the half-sister of Solange’s other children, Pauline and Eulalie. We meet Philippe Robillard, the half-Indian rogue who sweeps his cousin Ellen off her feet, and whose death in a bar fight in New Orleans prompts Ellen to marry Irishman Gerald O’Hara. Real historical characters make appearances (Rochambeau and Andrew “Old Hickory” Jackson), as do beloved fictional ones (Rhett Butler, Beatrice Tarleton, Ashley Wilkes, Frank Kennedy).

As I was typing the above potted summary, I thought “Well, that sounds pretty interesting.” Unfortunately, that’s not really what Ruth’s Journey actually conveys. Back in March, McCaig and Atria editor Peter Borland told the New York Times that they wanted to give Mammy a story and a voice. They have, but it’s largely used as a lens through which to project the saga of Scarlett O’Hara’s ancestors. This wouldn’t be cause for complaint except that these other characters emerge as more interesting than Ruth does, and that’s a shame. It’s unrealistic to expect any derivative work to match up to Gone With the Wind. And authors are entitled to their own writing styles. However, one of the things that certainly draws readers in to Gone With the Wind is Margaret Mitchell’s languid, illustrative prose. I remember first reading it as a teenager and feeling like I could step through the pages and be in the story; Rhett Butler, Scarlett O’Hara, and even Mammy seemed so lifelike. Of course, Mitchell did allot 1,000+ pages for her original tome, and Gone With the Wind only spans about 20 years, but she took the time to describe everything from the land surrounding Tara to the elaborate clothes women wore, all of which has allowed readers to fully immerse themselves in the story. In contrast, McCaig attempts to cram nearly 60 years into less than 400 pages. This, combined with his stilted prose, results in flat characters and a plot that hastily skips from one event to the next without giving much weight or depth to any particular incident (when Scarlett’s first period is more memorable than Ruth’s trip to the slaver’s auction house, there might be an issue). Therein lies the central problem of Ruth’s Journey. It doesn’t really focus on Ruth or the experiences of slaves during the antebellum era (or indeed any of the characters therein). And when it does touch on issues like discrimination and cruel treatment at the hands of white people, it’s not written with enough attention or detail to make us feel for these characters. McCaig attempts to make Ruth stand out a bit by revealing that she has second sight – she can predict the future and knows when people aren’t long for this world because she can see their auras (voodoo magic?). But because this isn’t a dynamic characteristic until the end of the book, it ends up seeming gimmicky.

Ruth’s Journey isn’t a terrible book. It’s readable, and it will likely appeal to fans who love anything and everything related to Gone With the Wind. But it doesn’t do much in the way of righting the wrongs in the original story, and sadly, although Mammy may have a voice, she remains largely in the shadows.

I think I’ll re-read Gone With the Wind.

Ruth’s Journey by Donald McCaig is available from Atria Books

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠