It was with sadness that I learned last week of the death of Suzanne Farrington, Vivien Leigh’s only child. She passed away presumably at home in Lower Zeals, Wiltshire, of unstated causes at age 81. Many people know of her, but few outside her family and immediate circle seem to know much about her. The death announcement in the Telegraph told us that she lived a life of love and laughter and is survived by her three sons, 12 grandchildren and numerous friends, while a longer obituary in the same paper focused more on Suzanne’s tenuous relationship with her famous mother than her individual accomplishments as a woman, wife and mother.

Who was Suzanne Farrington, really? While conducting research for Vivien Leigh: An Intimate Portrait, meeting Suzanne was like trying to reach the summit of Mount Everest when I wasn’t an experienced climber. There was a shroud of protective secrecy surrounding her that was carefully held in place by several gatekeepers.

“Have you talked to Suzie?” many people asked me. I had not, I said, but I hoped to. I questioned everyone I interviewed about her. Is she nice? What’s she like? She was indeed nice, they said, but she never talks about Vivien, “I mean, she was basically abandoned by her mother.” And there was often the added reminder that “she doesn’t look much like Vivien.” Trader Faulkner told me of an embarrassing gaffe he made when he met Suzanne once at Notley Abbey. “You’re not like your mother, are you?” he said to her, without thinking. “No,” she responded. “Thank God.”

Whether Suzanne’s reluctance to talk about her life stemmed from lingering feelings of resentment over the atypical relationship she shared with Vivien, or the constant and unfair comparisons to her mother, or some other reason entirely, I was aware from the beginning and respected her want for privacy. And so I explained to my interviewees that my goal was not to push for information about her private life but rather to get her blessing for a project that was very near and dear to me. See, in my experience, I find it better to meet people in person rather than rely on formal letters through lawyers or other intermediaries. I feel that a face-to-face meeting (or even a direct email or phone call) allows people to see what I’m really about and helps me to assure them that I’m not some random crazy person out to write a tabloid-style exposé on their famous relative or friend.

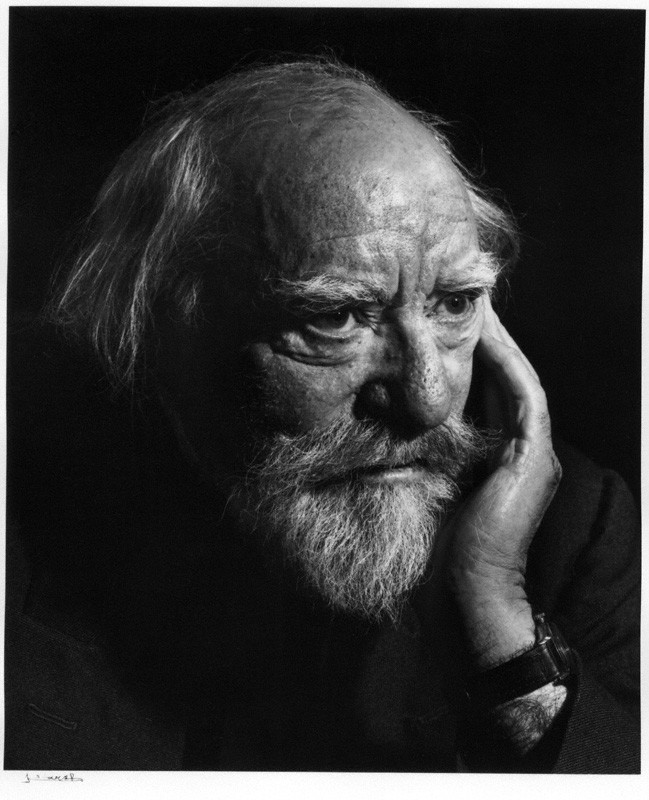

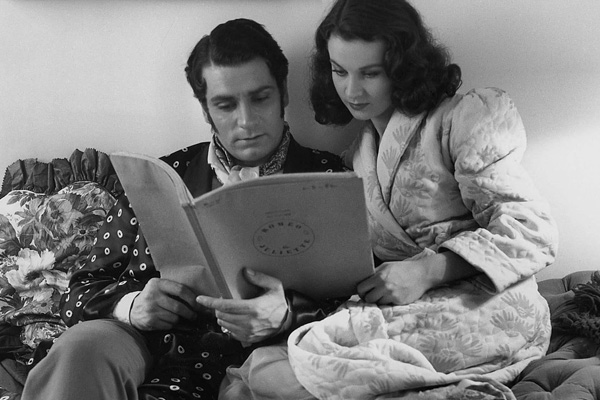

Vivien and Suzanne at Suzanne’s wedding to Robin Farrington, December 1957

Vivien and Suzanne at Suzanne’s wedding to Robin Farrington, December 1957

There were several of Vivien Leigh’s letters in the Laurence Olivier Archive that I was determined to use; I felt that even if I couldn’t quote the letters in full, extracts would add something special to my book. This being my first foray into book writing, I wanted to make sure I did everything the right away. I figured the powers that be would recognize that if I had wanted to write some sort of trashy tell-all about Vivien, I wouldn’t even bother asking permission for anything. Right? So I carefully drafted a letter to Suzanne stating my mission and telling her about myself and the work I’d done so far. Then I sent the letter via her lawyer, who passed it on for me (though not, I strongly suspect, with any sort of word of encouragement. It is, after all, a firm that represents high profile clients like Rupert Murdoch). Then I waited. And waited, and waited some more. There were moments of great stress thinking about what she might say, if anything. I even remember dreaming about it once – of receiving a letter that said yes, you can use my mother’s letters! After about three months, I received a curt email from the lawyer saying he regretted to inform me that neither Suzanne nor Joan Plowright (who I hadn’t enquired about) was willing to let me use anything under their copyright. No explanation as to the reason why. Just a swift “No, sorry.” I was at the BFI Library going through Vivien’s letters in the Jack Merivale papers at the time, and I went into the bathroom and cried. It seemed like the worst thing that could happen; that possibly all the time and effort I’d already put in to research and making contacts was for nothing and this book would never come to fruition.

It was a crushing blow, but I refused give up.

Some of my interviewees, after our meetings, were eager to help. Vivien’s sister-in-law, Hester St John-Ives (who sadly passed away just after Christmas last year), was friendly with Suzanne and offered to phone and vouch for me. She wasn’t able to reach her, but I greatly appreciated the kind effort. Others flat out told me that Suzanne wouldn’t want to meet with me; and there were also those who didn’t feel like they could even talk about Vivien because they were good friends with Suzanne and had already talked to x biographer ages ago.

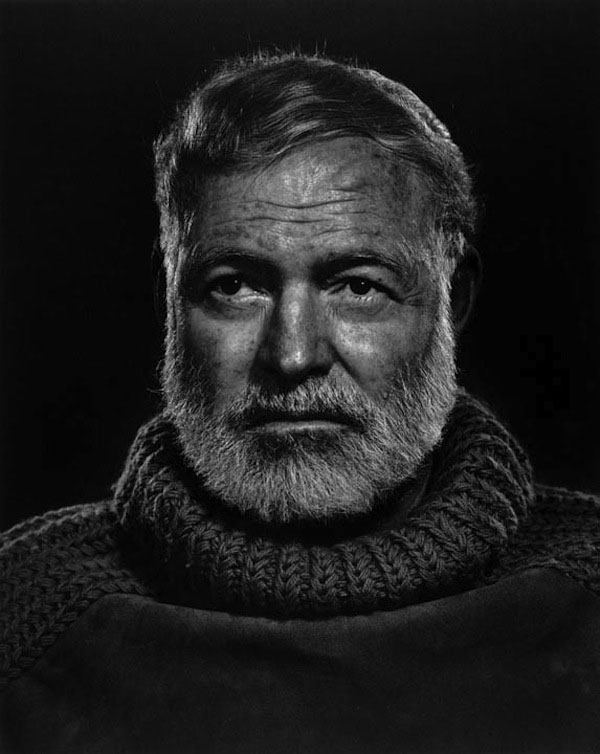

Vivien with Suzanne and first-born grandchild, Neville Farrington, 1958

Vivien with Suzanne and first-born grandchild, Neville Farrington, 1958

“I wish you had been doing this when Peter Hiley was still alive,” Hester said to me while we had lunch at her house in Devon one January day back in 2013. Hiley, who had worked for both the Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier estates since the two of them were still alive and married to one another, had been the link between biographers like Hugo Vickers (and I assume others) and Suzanne. Alas, Hiley died in 2008, just a year after I launched this website and a year before I decided I was going to embark on the journey of publishing a book about Vivien. Full disclosure: in 2009 I hadn’t the slightest idea how to go about getting a book published so even if Hiley had still been with us, I probably wouldn’t have known to get in contact anyway.

In the end, I never got to meet Suzanne. But as Mick Jagger once aptly pointed out, “You can’t always get what you want. But if you try, sometimes you just might find you get what you need.” Days before my submission deadline, I was contacted by Hugo Vickers who had encouraged my enthusiasm from the beginning. Having presented Suzanne with second a letter I had written, she finally said yes. For that I’m eternally grateful.

This brings us back to the question “Who was Suzanne?” As a Vivien Leigh fan, I know I speak for many when I say that it would have been great if she’d opened up about her mom in a documentary or something. As a writer, in the absence of a direct interview, I relied on interviews and quotes she gave to the press in the years before Vivien’s death (this one continues to be one of the most popular posts on this site for some reason).

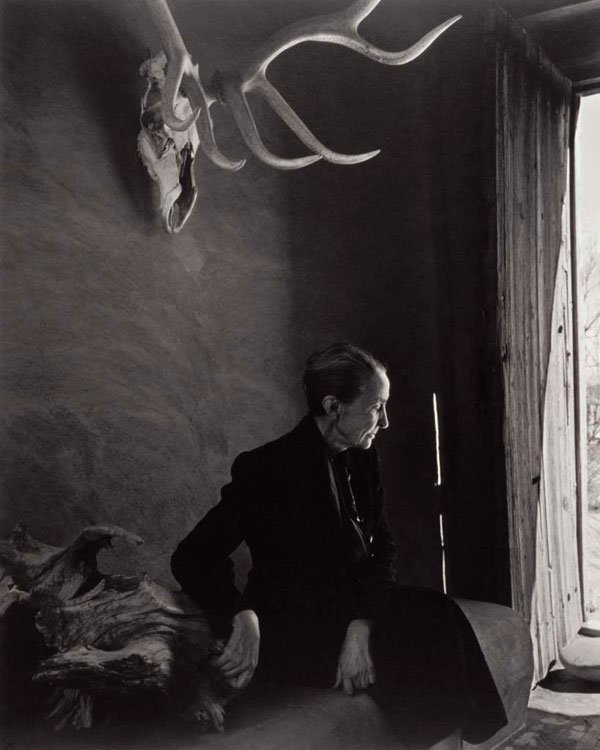

Suzanne and her grandmother, Gertrude Hartley, early 1970s

Suzanne and her grandmother, Gertrude Hartley, early 1970s

I think it’s natural for us fans to wish Suzanne had spoken more about her relationship with Vivien, but I also believe her silence is to be equally respected and admired. By keeping herself from the spotlight, Suzanne was able to live her own life away from Vivien’s ever-present shadow. She put her family and friends first, and reaped the benefits. Those of us who never had the privilege of meeting her may never know who she really was. But she did bequeath us with an extraordinary gift in the form of her mother’s papers, now safely ensconced at the Victoria & Albert Museum in London. And that, I think, is more than enough.

If any of you had the privilege of meeting Suzanne, please feel free to comment. I’d love to hear your story!

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠