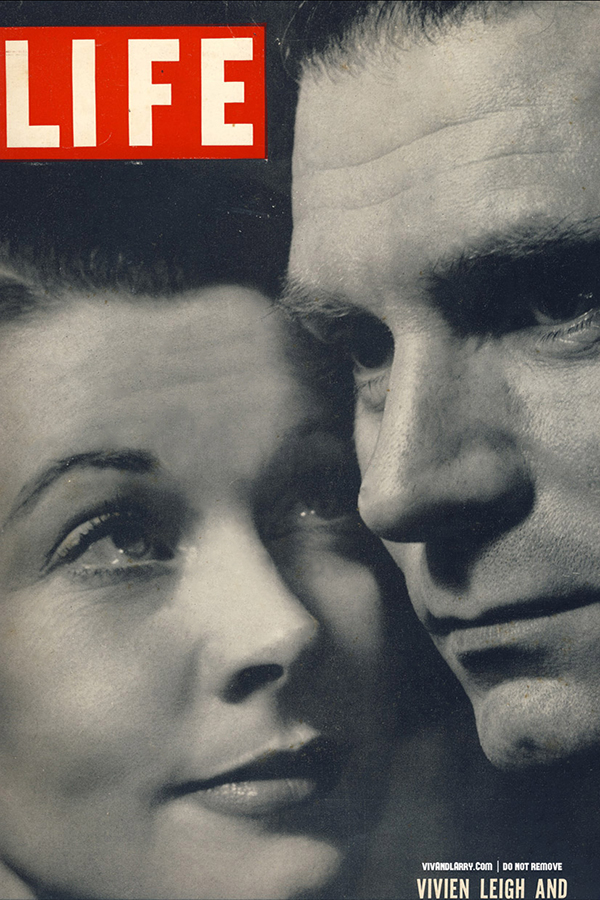

The Romantic Truth about Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier

by Ruth Waterbury

Photoplay, December 1939

What happened to romance in Hollywood?

Oh, I know that love, love, love is shouted from the Beverly Hilltops; that caresses are recorded by scores of news cameras; that people are proclaimed “this way” and “that way” in headline type. But most of these are mere flash flirtations quickly entered into and even more quickly forgotten.

But what has happened to the old-time romance that defied the studios, challenged the conventions – and diverted the public? What has happened to the love that laughs at locksmiths, that must find a way to happiness in the face of every obstacle society can place in its path?

True, there have been many recent Hollywood marriages founded on abiding love. But they are, most of them, quite definitely marriage of convenience, mergers of affection blended with a keen consideration of the future. Hollywood, built upon the quicksands of public approval, dedicated to one of the most precarious professions in the world, has grown shrewd and cautious. That’s why, today, Hollywood is startled at the sudden intrusion of real romance into its present calm.

For the greatest love story in town today is far from cautious and calm. The love between Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier is romance – that high, tumultuous romance that laughs at careers, hurdles the conventions, loses its head along with its heart, and laughs for the exhilarating joy of such wildness.

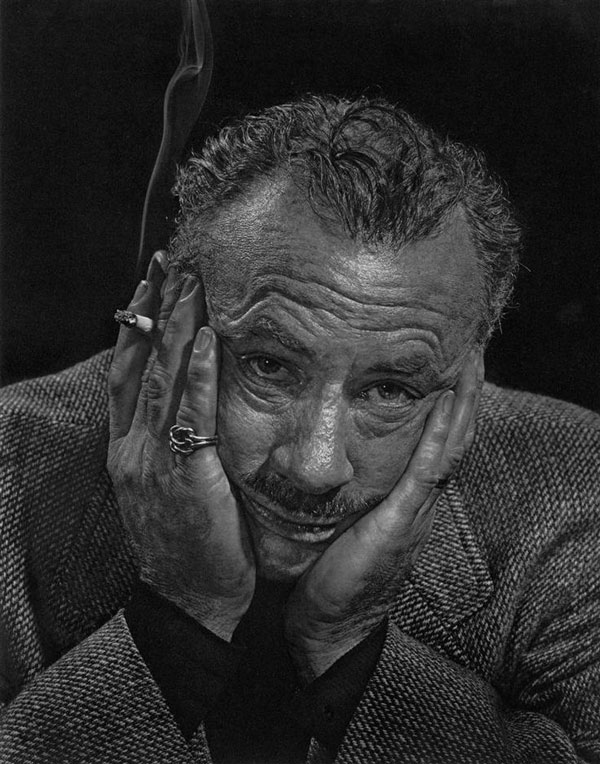

These two are the most provocative, least known, most potential personalities now exciting filmdom. The lucky insiders who have already seen “Gone With the Wind” are afire with enthusiasm over Vivien Leigh’s Scarlett O’Hara. They proclaim that her work therein makes her one of the greatest stars in the entire film firmament. And the surly, smoldering Heathcliff of “Wuthering Heights” that Olivier revealed last winter, backed up by his later going to the opposite extreme and giving a high comedy performance in “No Time for Comedy” on Broadway, makes him the rarest, most valuable of combinations, the handsome man with sex appeal who is also a superlative actor.

Such being the case, it would be sensible for Miss Leigh and Mr. Olivier to forget each other or to avoid going, as they are about to, through the British divorce courts (which are not nearly so polite as our own).

Yes, indeed, it would have been much more sane if they had let the bright flame burning between them die down, dampened by the demands of their careers and of smug respectability. It would have been sensible, but it would not have been glory and fever of the blood and the intensity of living. And therefore it did not, and it will not, happen with Larry and Vivien.

Shortly before the approaching new year, unless something goes seriously amiss, their respective mates will go to court to free them. They have waited many months for this moment, and they don’t know yet what freedom may cost them. They each have a child which perhaps they will never be permitted to see again. They may have to listen to some pretty severe things said about them, the English not being inclined to mince such matters. Larry and Vivien care terribly about all that. There is a passion and vitality that touches both of them, that makes them care terribly about all things. But they care more for each other. They care more for each other than they do for money or careers or friends or harsh words or even life itself. And this is the story of why they do.

They met, three years ago, when they were cast opposite in a London play called “The First and the Last Time” [KB The First and the Last, released in the US as 21 Days Together]. Three years ago, Vivien Leigh aged twenty-four, wife of Herbert Leigh Holman, distinguished barrister, was a promising young actress. Three years ago, Laurence Olivier, aged twenty-nine, husband of Jill Esmond, was London’s most distinguished young actor. Their artistic lives were in a mess, but they were very British, both of them, brought up in the best traditions of the Empire, of a good school tie and all that, so they never discussed such subjects.

Mr. Olivier, leading man, was presented to Miss Leigh, leading lady, and they said nothing more on that momentous occasion than any other well-bred English pair would have said, which means saying nothing whatsoever in a very brittle way. Nevertheless, one pair of exotic, green eyes looked deep into a pair of passionate, hungry brown eyes and forthwith said more than the entire unabridged Oxford dictionary.

Even at that, nothing might have come of it had not their work and their families and even fate itself tried so hard to keep them apart, thereby bringing out the rebellious determination within each of them, making everything about each other seem glamorous indeed if for no other reason save that to experience this happiness was forbidden.

For they came together at the exact psychological moment when each was seeking freedom and self-expression.

Both of them, initially, had married too young. Vivien, who had taken her husband’s name for her stage work, had been born Vivien Hartley, the most respectable and beautifully brought up young daughter of a British Cavalry officer stationed in India. She had absorbed the best education money could and social position could buy. At eight she had been sent to a convent school just outside London and stayed there until she was fourteen, when she was transferred to a school on the Italian Riviera. That was followed by a year in art school in Paris and another at the Royal Dramatic Academy in London. She left that, confident of conquering the world and all the London managers, but the best she got was “walk-ons.” Thus, when Herbert Leigh Holman came along and proposed to her, her unemployed dramatic instinct told her that it was most fascinating to think of being a married woman before she was twenty, and later, before she was twenty-two, to be a mother.

Laurence Olivier’s wife was Jill Esmond, the actress. The Olivier-Esmond love had been much written about. Larry was originally very much in love with Jill, but he was undoubtedly much in love with the actress as he was with the woman. He had always adored the theater. Coming up in London, getting the occasional bits to play, he was enormously impressed with meeting Jill Esmond, daughter of a famous acting family, and almost overcome when he realized that she was falling in love with him. Jill was all that he was not – important, established, well-trained theatrically. When she got an opportunity to come to America for a show, Larry made his debut with her in “Private Lives” on the New York stage. When she went back to England, he returned, too. Then he got a chance at a movie test for RKO, but Jill stood in with him on it, and when it came time to draw up the contracts, it was Jill they wanted most, although they both signed up.

It was Larry’s good luck, in disguise, that made everything turn out badly. RKO advertised him as a “second Colman” and since he was nothing of the sort both the studio and the public were disappointed upon seeing him. Jill didn’t set the screen on fire, either, so when their options weren’t taken up the Oliviers went back to London.

Then Hollywood beckoned again. Laurence was needed for the lead opposite Garbo in “Queen Christina.” The rush was so great that he had to cable his measurements so that his costumes could be ready for him on landing. He came across the ocean on the fastest boat, across the country on the fastest plane. Everything was ready for him except Garbo. Garbo insisted on John Gilbert for the role.

The bitterness engendered in Larry Olivier by this went toward making him the great performer he was in “The Green Bay Tree.” To act magnificently now became an absolute compulsion. Through frustration, his brilliant mind developed a sardonic twist. His naturally pleasant personality became fierce and rebellious. When he met Vivien Leigh, also disillusioned and revolutionary at heart, it was flame meeting flame. A conflagration was bound to result and did.

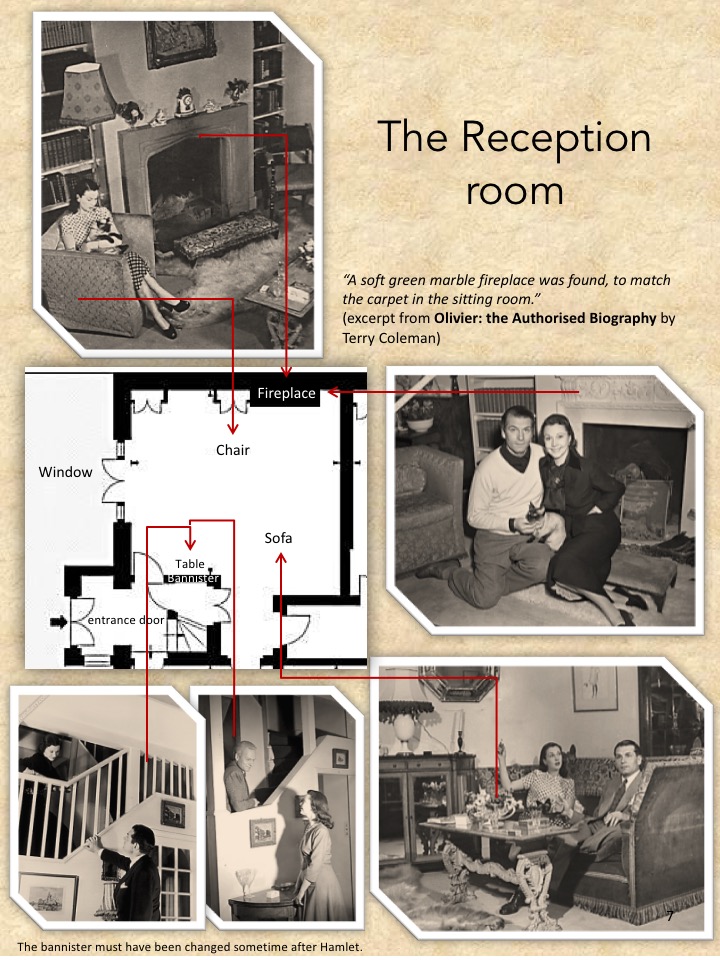

They instantly discovered each other and the ambitions and dreams they had in common. The bright sun of mutual success shown upon them. They were triumphant artistically and commercially. They even did a production of “Hamlet” together, Vivien playing Ophelia to Laurence’s melancholy Dane. Long before that they had known that they were in love, but after that production all London and their respective mates knew it.

When Laurence Olivier came to Hollywood for the third time last winter, everyone saw the change in him. He was no longer shy or inhibited. He did not mingle with the few friends he had made out here on his previous visit. He did exactly as he pleased, staying by himself because he was so much in love he needed no companionship.

The Vivien Leigh came visiting Hollywood, and met Myron Selznick, brother of David, and through the accident of that meeting got the test that resulted in her being chosen as Scarlett. That was thrilling, but actually she lived through a lonely winter because almost as soon as she arrived, Larry’s stage play took him away from her. But he left the play as soon as he possibly could to come westward to be near her, since “Gone With the Wind” was not yet finished.

They still don’t see many people. They dine a lot with director George Cukor and see a few members of the English colony but they are still at that stage where they prefer to be alone together. And therein, too, they act not at all like the lovers of Hollywood who always seem to make their vows at the Troc or to exchange their first kiss Frida night at the fights. The emotion between them is too intense and sincere for any of that calculated demonstration. They dine in the quietest restaurants and do no calling save upon each other. They are moody, too, with the moods of true romantics – all laughter and joy one moment, all fiery intellect or fierce conversation the other.

They will have to wait at least another full year before they can marry. So during that year watch for some very great performances, Larry’s as Max de Winter in “Rebecca” and Vivien in any one of the several big productions Selznick is planning for her. They will inevitably give great acting portrayals, living as they are now through those exciting, vivid moments of human life that breed true artistic creativeness.

As for what will happen to them after they wed – well, we were talking of romance – and matrimony is quite a different story.

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠