I’m mainly writing this post because I’m doing a presentation on Michael Redgrave in the Traditions of British Cinema course tomorrow, and I find that writing things helps me retain information better. The topic we are focusing on in class this week is the Victorian Theatre and Adaptation, and the screening is The Importance of Being Earnest (Anthony Asquith, 1956). But Michael Redgrave and Rachel Kempson were also good friends with the Oliviers, so, huzzah, relevancy for this website! Apologies in advance for this being more like an academic paper than a random blog post.

Michael Redgrave came from a theatrical family (both parents were actors), but acting wasn’t his first ambition. Educated at Cambridge, Michael wanted to be a poet, and after graduating he worked as a teacher before ending up on the stage in the early 1930s. He quickly established himself as a formidable classical actor and counted among his peers Laurence Olivier, Ralph Richardson, and John Gielgud, all of whom would be later regarded as theatrical giants.

British theatre stars of the 1930s were critical of working in film, and considered the stage the foremost place to showcase their talent. In their minds there was a big difference between being an actor and being a film star: acting was solely about the craft whereas being a movie star was more about making money. But it was precisely because the theatre offered such a small salary that many of these actors started doing films in the 30s. Films offered a supplemental income to continue honing their craft on stage.

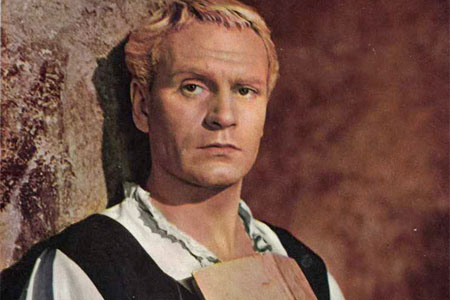

Michael Redgrave became a matinee idol after playing in Alfred Hitchcock’s film The Lady Vanishes opposite Margaret Lockwood and Dame May Whitty, and unlike some of his fellow theatre actors, he seemed to merge seamlessly into film acting. In the 1940s he had a brief but failed career as a Hollywood screen star, and in the 1950s he started playing character parts on screen with the exception of two major films for director Anthony Asquith: The Browning Version (1951), adapted from Terrence Rattigan’s play, and The Importance of Being Earnest (1956) by Oscar Wilde. Also during this time Michael was lauded as one of the foremost classical stage actors of his generation, and newspapers suggested a “rivalry” between him and Laurence Olivier.

In his article “Postwar Films 2: Adaptation and the Theatre,” Tom Ryall observes that many classical British stage actors in the first half of the 20th Century had difficulty transitioning from stage to screen. They often appeared wooden or “stagey” when they were supposed to be natural. I don’t think Michael Redgrave really had as much of a problem with this transition than someone like Olivier. Michael understood the difference between acting for a physical audience and acting for the camera. He understood that the camera is intimate; that it can frame the actor and show subtle nuances and changes in expression that one would miss sitting in the theatre watching a live performance.

Even though The Importance of Being Earnest was closely adapted from Oscar Wilde’s play and Asquith frames it as a play within a film (as we can see by the opening and closing scenes), there is still a major difference between stage acting and more realistic acting within the film. This film was made during the period when Method acting was becoming really popular in the United States, and actors such as Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift were making waves for digging for emotions within themselves to add realistic depth to their performances. Dame Edith Evans, who had just started acting in films after a long career on the stage, gave a performance in Earnest that is widely called “theatrical,” whereas Michael Redgrave gave a more subtle, quiet, natural performance to try and make it seem more like a film and less like a filmed stage performance (although it should be noted that Michael’s performance in Earnest is still theatrical compared to his performances in The Browning Version or The Lady vanishes). Unfortunately for Michael, Edith Evans’ extremely over-the-top Lady Bracknell is the character that’s most remembered today.

Finally, a major part of Michael Redgrave’s life and work was his homosexuality, and Stephen Bourne suggests that both The Importance of Being Earnest and The Browning Version contain homosexual undertones that probably passed over many critics and viewers in the 1950s. Both Oscar Wilde and Terence Rattigan were gay, as was director Anthony Asquith in times when homosexuality was illegal and punishable by going to prison (as was experienced by Oscar Wilde shortly after the play was published and later Redgrave’s colleague John Gielgud). Theatrical circles were one of the only places that homosexuality was accepted at the time.

It could be argued that the scenes from Earnest and The Browning Version that are most mentioned by scholars can be read as a form of liberation from the oppressive and homophobic societies these artists lived in. According to Bourne, the homosexual undertones in Earnest are closer to the surface than in any other Oscar Wilde Play, and the scene most referenced is the one in which Algernon and Jack/Earnest talk about bunburying. Bunburying meaning inventing another identity with which to pursue pleasures that are unconventional. In The Browning Version, some scholars argue that Taplow’s liking and sympathy for Mr. Crocker-Harris (Redgrave) was actually homosexual in nature.

Whether Earnest and The Browning Version were intended to be read in this way or not, Michael Redgrave’s personal life often affected his stage and screen performances. To the theatre and film-going public, he was a heterosexual leading romantic actor. He was married to Rachel Kempson for over 50 years, but it was widely acknowledged by his wife and his acting peers that he preferred men, however he was never publicly open about it, and it didn’t come out until his son Corin published his book Michael Redgrave My Father after Michael passed away. Still, he often displayed a sensitivity in his roles that was missing from the interpretations of characters that his peers made. His biographer Alan Strachan mentions how Michael usually infused a sense of guilt into his characters and performances that reflected the inner turmoil of his off-screen/stage life. In this way, I think he was more of a method actor than perhaps even he realized.

++++

Of course, Michael appeared opposite Laurence Olivier in several stage plays and films, but he and Rachel Kempson were friends of both Larry and Vivien Leigh in real life. Larry was even godfather to Michael and Rachel’s eldest daughter, Vanessa. The Oliviers were invited to Beford House in Chiswick Mall to watch the Oxford-Cambridge boat race every summer, and the Redgraves often visited Notley Abbey. Rachel was one of Vivien’s closest friends and confidants, especially during Vivien’s affair with Peter Finch. Michael always admired Larry as an actor and though there may have been a few scrapes here and there, I don’t think there was any real rivalry between them. Michael was also set to star opposite Vivien in Edward Albee’s play A Delicate Balance but she died before the first performance.