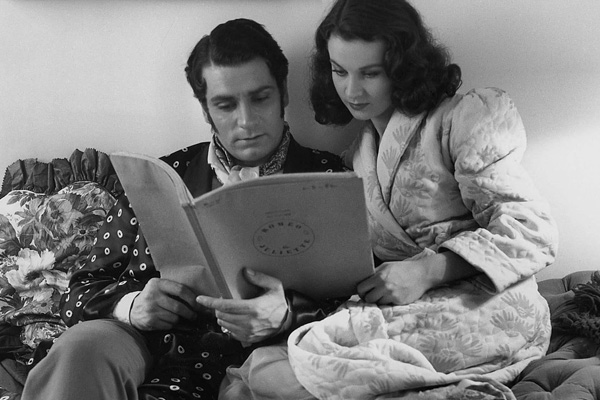

In December 1946, Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier were chosen by Strand magazine in London to contribute literary quotes from their personal Commonplace Books. Commonplace Books (commonly referred to today as “inspiration journals”) are blank notebooks that differ from traditional diaries in that they’re not meant to record life events in a chronological order. Rather, they’re a random hodgepodge of thoughts, quotes and passages from books, sketches, recipes, etc. that made an impression in the moment.

Strand printed a running series called “The Commonplace Books of…” where “Every month [they] publish quotations from the Commonplace Books of people whose names you know and whose wide reading you envy.” While the choice of works the Oliviers quote from may seem familiar from what we have read about them in biographies, what is interesting is what these particular quotes reveal about their individual personalities. To me, Vivien seems like a dreamer, whereas Larry Olivier comes off as a romantic.

What do you think of this list?

Vivien Leigh

Entries in my Commonplace Book are very varied and I am continually adding to them. My favorite quotations include “The Cloths of Heaven” by W. B. Yeats:

Had I the heavens’ embroidered cloths

Enwrought with gold and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths,

Of night and light and the half light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet;

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams

And that memorable sentence on the death of William III, the last sentence in J. L. Motley‘s “Rise of the Dutch Republic”:

As long as he lived, he was the guiding star of a brave nation, and when he died the little children cried in the streets.

In humorous prose I like the entry of April 23rd in “The Diary of a Nobody” by George and Weedon Grossmith:

Mr. and Mrs. James (Miss Fullers that was), came to meat-tea, and we left directly after for the Tank Theatre. We got on a bus that took us to King’s Closs, and then changed to one that took us to the Angel. Mr. James each time insisted on paying for all, saying that I had paid for the tickets and that was quite enough.

We arrived at the theatre, where, curiously enough, all our bus-load except and old woman with a basket seemed to be going in. I walked ahead and presented the tickets. The man looked at them, and called out “Mr. Willowly! Do you know anything about these?” holding up my tickets.

The gentleman came to, came up and examined my tickets and said: “Who gave you these?” I said rather indignantly: “Mr. Merton, of course.” He said: “Merton? Who’s he?” I answered rather sharply, “You ought to know, his name’s good at any theatre in London.” He replied: “Oh! is it? Well it ain’t no good here. These tickets, which are not dated, were issued under Mr. Swinstead’s management, which has since changed hands.”

While I was having some very unpleasant works with the man, James, who had gone upstairs with the ladies, called out: “Come on!” I went up after them, and a very civil attendant said: “This way, please, Box H.” I said to James: “Why, how on earth did you manage it?” And to my horror he replied: “Why, paid for it, of course!”

This was humiliating enough, and I could scarcely follow the play, but I was doomed to still further humiliation. I was leaning out of the Box, when my tie – a little black bow which fastened on to the stud by means of a new patent – fell into the pit below. A clumsy man not noticing it, had his foot on it for ever so long before he discovered it. He then picked it up and eventually flung it under the next seat in disgust. What with the Box incident and the tie, I felt quite miserable. Mr. James, of Sutton, was very good. He said: “Don’t worry – no one will notice it with your beard. That is the only advantage of growing one that I can see.” There was no occasion for that remark, for Carrie is very proud of my beard.

To hide the absence of the tie I had to keep my chin down the rest of the evening, which caused a pain in the back of my neck.

Of many favorite passages in Shakespeare, I like best of all the last speech of Oberon in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” from which these lines are taken:

Never more, hair, nor scar,

Nor mark prodigious, such as are

Despised in nativity,

Shall upon their children be.

And the 29th Sonnet, beginning,

When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s

eyes,

I alone be weep my outcast state…

I have read a great deal of Thomas Hardy and Dickens. The chapter on sheep-shearing in “Far from the Madding Crowd” ranks, I think, among the finest descriptive writings. With these I also place the beginning of “The Battle of Life” from Dickens “Christmas Books” – the description of the field from which “the painted butterfly took blood into the air upon the edges of its wings.”

For pure joy of reading I choose the reunion scene at the end of “Pickwick Papers”:

…. The coaches rattled back to Mr. Pickwick’s to breakfast, where little Mr. Perker already awaited them.

Here, all the light clouds of the more solemn part of the proceedings passed away; every face shone forth joyously, and nothing was to be heard but congratulations and commendations. Everything was so beautiful! The lawn in front, the garden behind, the miniature conservatory, the dining-room, the praying room, the bedrooms, the smoking room, and above all the study with its pictures and easy chairs, and odd cabinets, and queer tables, and books out of number, with a large cheerful window opening upon a pleasant lawn and commanding a pretty landscape, just dotted here and there with little houses almost hidden by trees; and then the curtains, and the carpets, and the chairs, and the sofas. Everything was so beautiful, so compact, that there really was no deciding what to admire most.

And in the midst of all this stood Mr. Pickwick, his countenance lighted up with smiles, which the heart of no man, woman, or child could resist: himself the happiest of the group, shaking hands…over and over again with the same people, and when his own were not so employed, rubbing them with pleasure; turning round in a different direction at every fresh expression of gratification or curiosity, and inspiring everybody with his looks of gladness and delight.

And, finally, a quotation from Plato which is, I think, particularly appropriate at the present time:

Then tell me, O Critias, how will a man choose the ruler that shall rule over him? Will he not choose a man who has first established order in himself, knowing that any decision that has its spring from anger or pride or vanity can be multiplied a thousand fold in its effects upon the citizens?

Laurence Olivier

Nearly all of my leisure reading is Shakespeare. May passages from the works of that greatest of poets come to my mind, notably Burgundy’s speech in “Henry V,” Act V, and part of the concluding chorus in the Epilogue, which runs:

Thus far, with rough and all-unable pen,

Our bending author hath pursued the story,

In little room confining mighty men,

Mangling by starts the full course of their glory.

Small time, but in that small most greatly

lived

This star of England: Fortune made his sword;

By which the world’s best garden he achieved,

And of it left his son imperial lord.

Here are four other of my favorite sonnets from Shakespeare’s plays:

Brutus in “Julius Caesar”

(Act IV, Scene iii)

There is a tide in the affairs of men,

Which, taken at the flood, leads on to fortune;

Omitted, all the voyage of their life

Is bound in shallows and in miseries.

On such full sea we are now afloat;

And we must take the current when it serves,

Or lose our ventures.

The Boy’s Song in “Measure for Measure”

(Act IV, Scene i)

Take, O, take those lips away,

That so sweetly were forsworn;

And those eyes, the break of day,

Lights that do mislead the morn:

But my kisses bring again, bring again;

Seals of love, but seal’d in vain, seal’d in vain.

Holofernes in “Love’s Labour’s Lost”

(Act IV, Scene iii)

This is a gift that I have, simple, simple;

a foolish extravagant spirit, full of forms,

figures, shapes, objects, ideas, apprehensions,

motions, revolutions: these are begot in the

ventricle of memory, nourished in the womb

of pia mater, and delivered upon the mellowing

of occasion. But the gift is good in those

to whom it is acute, and I am thankful for it.

The First Murderer in “Macbeth”

(Act III, Scene iii)

The west yet glimmers with streaks of

day:

Now spurs the lated traveller apace

To gain the timely inn; and near approaches

The subject of our watch.

I am also very fond of the two songs dedicated to Spring and Winter which come at the end of “Love’s Labour’s Lost.” Of other poets, Keats has always been one of my favorites. There is a delightful stanza from his “Ode to a Grecian Urn”:

Thou still unravish’d bride of quietness,

Thou foster-child of Silence and slow Time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loth?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

In prose, I share with my wife a liking for both ‘The Diary of a Nobody’ and Hardy’s “Far from the Madding Crowd.” I am an admirer of Rupert Brooke, especially the first half of that poem “The Great Lover,” which begins:

I have been so great a lover: filled my days

So proudly with the splendour of Love’s praise,

The pain, the calm, and the astonishment,

Desire illimitable, and still content,

And all dear names men use, to cheat despair,

For the perplexed and viewless streams that bear

Our hearts at random down the dark of life.

My favorite quotations would be incomplete without the first stanza of Gray’s “Elegy”

The curfew tolls the knell of a parting day

The lowing herd winds slowly o’er the lea,

The ploughman homeward plods his weary way,

And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

– an this memorable verse by William Allingham:

Four ducks on a pond,

The blue sky beyond,

White clouds on the wing.

What little thing

To remember for years,

To remember with tears.

Add these books to your shelf:

- The Collected Poems of William Butler Yeats (Wordsworth Poetry Library)

- The Rise of the Dutch Republic by John Lothrop Motley (Free on Kindle)

- Diary of a Nobody by George and Weedon Grossmith (Wordsworth Classics)

- A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare (The Oxford Shakespeare)

- The Sonnets and A Lover’s Complaint by William Shakespeare (Penguin Classics)

- Far from the Madding Crowd by Thomas Hardy (Penguin)

- A Christmas Carol and Other Christmas Writings by Charles Dickens (Penguin Classics)

- The Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (Penguin Classics)

- Timaeus and Critias by Plato (Penguin Classics)

- Henry V by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library)

- Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library)

- Measure for Measure by William Shakespeare (Modern Library)

- Love’s Labour’s Lost by William Shakespeare (Folger Shakespeare Library)

- Macbeth by William Shakespeare (Pelican)

- The Complete Poems of John Keats (Penguin) | Bonus material: Bright Star (Jane Campion, 2010)

- The Collected Poems of Rupert Brooke (Pomona Press) | Bonus material: Song of Love: The Letters of Rupert Brooke and Noel Olivier by Pippa Harris (Crown)

- The Poetry of Thomas Gray (Portable Poetry)

- The Collected Poems of William Allingham (CreateSpace)

♠ ♣ ♠ ♣ ♠