This post is for the Dynamic Duos blogathon currently being hosted by Once Upon a Screen and Classic Movie Hub and I’d highly encourage reading the entries from all the other fabulous bloggers. I apologize in advance if what I wrote below seems a bit disjointed. There is so much to say about the Oliviers that one could literally fill an entire book.

+++

On May 22, 1960, Vivien Leigh released a shocking statement to the press: “Lady Olivier wishes to say that Sir Laurence has asked for a divorce in order to marry Miss Joan Plowright. She will naturally do whatever he wishes.” The reasons behind Olivier’s request remained unknown to the general public until 1977 – ten years after Vivien’s death – when biographer Anne Edwards revealed Vivien’s long-fought battle with manic depression (better known today as bipolar disorder) and Olivier’s inability to cope with the strain of her illness. In 1960, however, it was only clear that one of the most celebrated and respected relationships in show business had come to what seemed like an abrupt end. Many fans were so bowled over by the news that they decided to take matters into their own hands. Olivier’s papers in the British Library contain a multitude of hand-written letters from people around the globe imploring him not to go through with the divorce; they simply couldn’t handle the disillusionment.

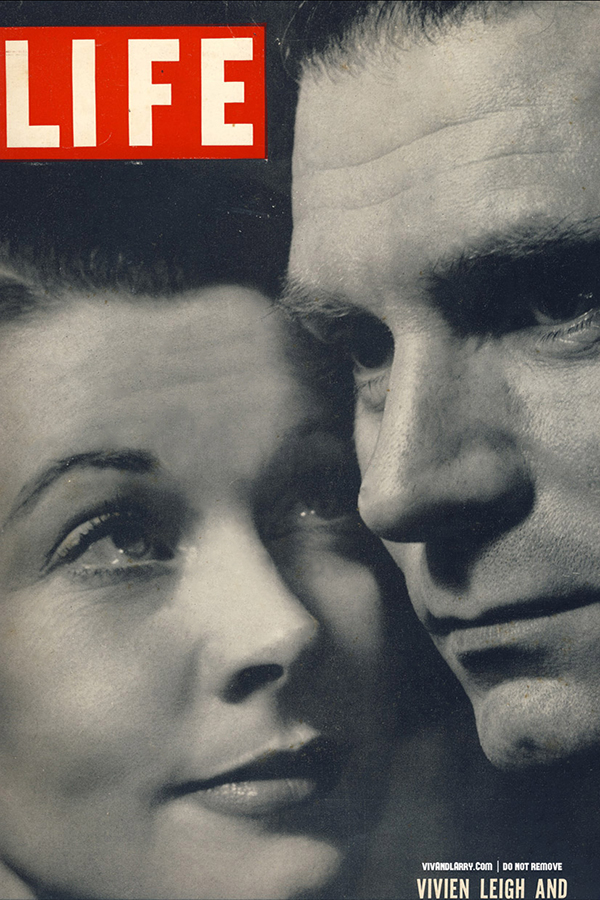

“I first set eyes on the possessor of this wondrous unimagined beauty in The Mask of Virtue, in which she had attracted considerable attention—though not, at this time, chiefly on account of her promise as an actress,” Olivier wrote in his autobiography Confessions of An Actor. “Apart from her looks, which were magical, she possessed beautiful poise; her neck looked almost too fragile to support her head and bore it with a sense of surprise, and something of the pride of the master juggler who can make a brilliant manoeuvre appear almost accidental. She also had something else: an attraction of the most perturbing nature I had ever encountered.” For Vivien, the attraction was instantaneous and total. In a 1960 interview with David Lewin, she admitted to telling a friend as far back as 1934 that she was going to marry Olivier some day. It didn’t matter that they were both already married to other people. Olivier was well on his way to becoming a great actor and Vivien wanted to make the journey alongside him.

Their medium of choice was always the theatre. Throughout the course of their relationship and even today there is an argument that Vivien was more natural and camera-ready, and therefore was better served on screen, whereas Olivier did better on stage. Whatever one’s personal viewpoints on who was a better actor, the facts are these: the idea that stage acting was superior to screen acting was a cultural and generational attitude amongst many classicaly-trained British actors of the day. But they still had to supplement their income with films.

The Films

Hungarian producer-director Alexander Korda is generally credited with the role of matchmaker in the Leigh-Olivier partnership. In 1936, he cast them as lovers in the Elizabethan costume picture Fire Over England. It was intended as a Flora Robson vehicle, but Korda saw the potential in the real-life love affair that sprung up between Vivien and Olivier during shooting, and wanted to build them up as an on-screen romantic couple.

They were again paired together the following year in a screen adaptation of John Galsworthy’s The First and the Last. Directed by Basil Dean, they play Wanda and Larry, young lovers who spend 21 days on the run after Larry accidentally kills Wanda’s perpetually absent husband. For me, the most interesting thing about this film is not what appears on screen, but what happened off-screen. In later years, the Oliviers were known for their rigid professionalism, but none of this was displayed during the making of what would eventually be titled 21 Days Together.

Basil Dean wrote of his frustration in attempting to direct the couple in his book Mind’s Eye. He had worked with Vivien before on the Gracie Fields film Look Up and Laugh, and found her nervousness difficult to control. This time he had to contend with a combination of nonchalance and mutual obsession between his two leads. Getting them to turn their attention away from each other and focus on the job at hand proved impossible. It’s easy to understand Dean’s frustration, considering his first choices for the lead roles had been Clive Brook and Vera Zorina. 21 Days ended up being Dean’s last film as a director, and Korda shelved it completely, only releasing it in 1940 after the successes of Gone With the Wind and Wuthering Heights. Vivien and Olivier went to see it in New York that same year, and reportedly walked out half way through.

That Hamilton Woman was the third and last film they made together, and for me it’s also the best and most interesting. In 1940, in the hopes of making enough money to sail home to England to help in the war effort, Vivien and Olivier poured their combines savings from their recent Hollywood film successes into a stage production of Romeo and Juliet. The production was a critical failure and they lost all of their money. Broke and stranded in the US, they need a way to raise funds. Enter Korda – again. The producer was in hot water with the British film industry for failing to return to England when the war broke out. Not wanting to be seen as a deserter by his adoptive country, he decided to film a historical, pro-British propaganda piece that combined elements of Hollywood grandeur. For his subject he chose the famous love story between Admiral Horatio Nelson and his mistress Emma Hamilton, and asked Vivien and Olivier to play the leads. The recent marriage between the two stars gave the film an extra romantic boost. The Oliviers’ relationship had taken on a somewhat mythical status in the eyes of the public since the announcement of their engagement following the premier of Gone With the Wind the previous year. Now, fans got the added bonus of watching them enact their real feelings through two historical characters.

At least one Vivien Leigh biographer has stated publicly that the reason why That Hamilton Woman was the last film Vivien and Olivier made together was because Olivier was jealous that Vivien out-acted him. I would argue against this opinion, mainly because it ignores the circumstances surrounding the film and the disparity between the Hollywood and British film industries at the time. There is a noticeable difference in acting styles in this film. Vivien is clearly the Hollywood star here. Olivier, on the other hand, agreed with Korda to act in accordance with the stoic and wooden morale-boosting style that defined British wartime cinema. So, while Vivien’s performance is much more lively and interesting to watch, it was actually Olivier who received most of the critical praise, especially overseas where he was named Best Actor by the influential British fan magazine Picturegoer.

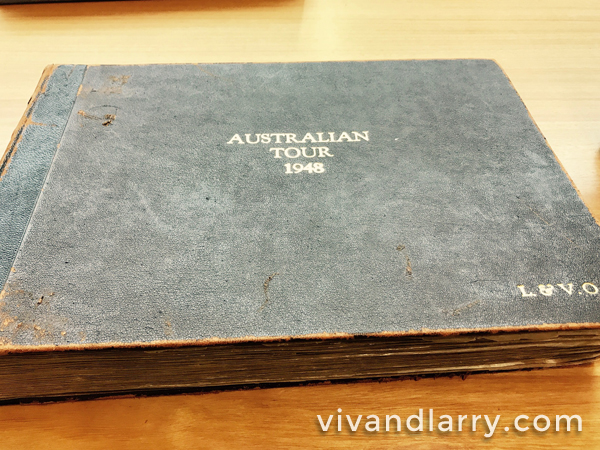

It is a shame that they didn’t make more films together. While Olivier found great creative success filming shakespeare in the 1940s and 50s, Vivien’s Hollywood stardom arguably prevented her from finding equal success on the British screen. It was in American cinema, ironically playing American women, where she really hit her stride. Returning home to London at the end of 1940, the Oliviers busied themselves developing their reputations on stage. They would go on to collaborate in 13 plays together, many of them classics, which eventually led to them being dubbed “Theatre Royalty.”

If it seems difficult today to understand the full scope of the Oliviers’ impact on popular culture during the mid-twentieth century and the significance of their breakup, consider this: In an industry where marriages are notoriously short-lived, they managed to keep it together for nearly 25 years despite being mutually ambitious, single-minded and competitive. Individually they both had great star power, but as a combined entity they managed to transcend mere celebrity and achieve legendary status. Of course, this didn’t negate the challenges of living their lives in the public eye, but Vivien and Olivier presented the picture of a close-knit team tied together by obsessional devotion to their craft and to each other. They were glamorous, talented, and perhaps most importantly, an intensely private couple which allowed their romantic image to remain largely untainted in the eyes of their fans despite personal hardship behind closed doors. It is this idea of a grand but tragic romance that continues to enthral people today.

Wow, excellent article. I love how well you know your subject and how you manage to be both immersed and yet objective. It’s pretty rare to get that combo.

Thanks, Neve!

Wonderful read, as always.

Excellent post and tribute to their relationship. I hadn’t realized the shock that their splitting up would cause, but you’ve given us good perspective. In fact, after reading your post, I felt a little sad myself that they broke up… 🙂

Thank you. I hasn’t quite realized the extent of the shock, either, until I read all hose fan letters in Olivier’s archive. They really were the ideal for a lot of people in the post-war years.

The Oliviers lived in a time when it was easy to keep certain things from the media.Nowadays, it would be on cable news 24 hours a day! No wonder people were shocked about their divorce!